Rhine campaign of 1795 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rhine Campaign of 1795 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the First Coalition | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 175,000 | 187,000 | ||||||

The Rhine Campaign of 1795 was a series of battles that took place from April 1795 to January 1796. During this time, two armies from Habsburg Austria fought against two armies from the French Republic. The Austrian forces, led by François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt, successfully defended against the French invasion. The French armies were trying to enter the southern German states, which were part of the Holy Roman Empire.

At the start, the French Army of the Sambre and Meuse, led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, faced Clerfayt's Army of the Lower Rhine in the north. In the south, the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle, under Jean-Charles Pichegru, was opposite Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser's Army of the Upper Rhine. A French attack in early summer failed. However, in August, Jourdan crossed the Rhine river and quickly captured Düsseldorf. His army then moved south to the Main River, cutting off Mainz. Pichegru's army also surprised the Austrians by capturing Mannheim. This gave both French armies important positions on the east side of the Rhine.

The French attack started well, but things changed when Pichegru missed a chance to capture Clerfayt's supply base at the Battle of Handschuhsheim. While Pichegru waited, Clerfayt gathered his troops and defeated Jourdan at the Battle of Höchst in October. This forced most of Jourdan's army to retreat back to the west side of the Rhine. Around the same time, Wurmser trapped the French forces at Mannheim. With Jourdan out of the fight for a while, the Austrians defeated part of Pichegru's army at the Battle of Mainz. In November, Clerfayt defeated Pichegru again at the Battle of Pfeddersheim, ending the siege of Mannheim. In January 1796, Clerfayt and the French agreed to a ceasefire. This allowed the Austrians to keep control of many areas on the west side of the Rhine. During this campaign, Pichegru was secretly talking with French Royalists. Historians still debate if Pichegru's secret actions, his poor leadership, or the unrealistic plans from Paris caused the French to fail.

Contents

Why Did the War Start?

The French Revolution began in 1789. At first, European rulers saw it as a problem only for the French king, Louis XVI. But as the revolution became more extreme, other kings and queens worried about their own power. They supported Louis and his family. In 1791, the Declaration of Pillnitz warned France of serious consequences if anything happened to the royal family. With support from Austria, Prussia, and Britain, French nobles who had left France tried to start a counter-revolution. On April 20, 1792, France declared war on Austria. This led to the War of the First Coalition (1792–1798), which involved Great Britain, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Roman Empire.

French Army Changes

After some early wins in 1792, France faced mixed results in 1793 and 1794. By 1794, the French armies were in a difficult state. Many old army units, especially the cavalry, had left with the king's relatives. As the Revolution became more radical after 1793, people suspected treason after every loss. The most extreme revolutionaries removed officers who might still be loyal to the old system. This meant losing many experienced leaders.

To fill the army, France started a levée en masse (mass conscription). This created a new kind of army with thousands of untrained men. Their officers were often chosen for their loyalty to the Revolution, not their military skills. New army units called demi-brigades were formed. Each combined one old royal army unit with two new units from the mass conscription. The French government, called the French Directory, believed that war should pay for itself. They did not plan to pay, feed, or equip their soldiers. This meant soldiers had to find their own food and supplies from the towns they were in. By early 1795, this new army was very unpopular in France. Soldiers often took what they needed, causing problems for the local people.

States of the Holy Roman Empire

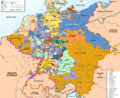

The German-speaking states on the east side of the Rhine were part of the Holy Roman Empire. Austria was a very important part of this empire. The French government saw the Holy Roman Empire as its main enemy in Europe. In 1795, the Empire included over 1,000 different areas. These ranged from very small states, sometimes just a few square miles, to larger areas like the Duchy of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Prussia. These states were governed in different ways. Some were independent cities, others were church-controlled lands, and some were ruled by powerful families. These states often worked together in groups called Imperial circles for things like trade and military protection.

The Rhine River's Importance

The Rhine River formed a natural border between the German states of the Holy Roman Empire and France. For either side to attack, they needed to control the river crossings. The Rhine was a wild and unpredictable river in the 1790s. Armies had to be very careful when crossing it. Between the "Rhine Knee" (a bend in the river) and Mannheim, the river had many channels, marshes, and islands. Floods from the mountains could quickly cover farms and fields.

Reliable crossing points were only available at specific places like Kehl (near Strasbourg), Hüningen (near Basel), and Mannheim in the north. Sometimes, a crossing could be made at Neuf-Brisach, but it was not good for large armies. Further north, past Kaiserslautern, the river had more defined banks with strong bridges for crossing.

By 1794–1795, French military planners in Paris saw the upper Rhine Valley and the Danube river basin as very important for France's safety. The Rhine offered a strong barrier against what the French saw as Austrian attacks. Controlling the crossings meant controlling access to the lands on both sides. For the French, controlling more German territory made them feel safer. This meant controlling the crossings from the east (German) side of the river.

French War Plans for 1795

Leaders in Paris believed that attacking the German states was necessary. The French government, the Directory, thought that war should pay for itself. They didn't set aside money to pay or feed their soldiers. So, it was important to get the armies out of France and into German lands as soon as possible. This helped with feeding the army by making the occupied territories responsible for supplies. However, it didn't solve all problems. The French soldiers' behavior, which made them unpopular in France, made them even more disliked in the Rhineland.

Soldiers were paid with paper money called assignat, which local people didn't want. This money eventually became worthless. After April 1796, soldiers were paid with metal coins, but even then, payments were often delayed.

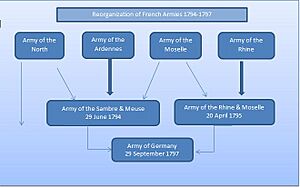

The French army was reorganized for these plans. The Armée du Centre (Army of the Center), the Armée du Nord (Army of the North), and the Armée des Ardennes (Army of the Ardennes) were combined to form the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. The remaining parts of the old Army of the Center and the Armée du Rhin (Army of the Rhine) were joined to create the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. This new army was led by Jean-Charles Pichegru.

The 1795 Campaign in Action

The Rhine Campaign of 1795 began with two Austrian armies, led by François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt, stopping French attempts to cross the Rhine River. The French wanted to capture the Fortress of Mainz. In the north, the French Army of the Sambre and Meuse, commanded by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, faced Clerfayt's Army of the Lower Rhine. In the south, the French Army of Rhine and Moselle, under Pichegru, was opposite Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser's Army of the Upper Rhine.

In August, Jourdan crossed the Rhine and quickly took Düsseldorf. His Army of the Sambre and Meuse then moved south to the Main River, cutting off Mainz. On September 20, 1795, 30,000 French troops under Jourdan began a siege of Mainz. The enemy soldiers inside the fortress secretly talked with the French about giving up. The French then used Mainz as a base for much of the 1795 campaign.

With their successes at Düsseldorf and Mainz, the French armies had strong positions on the east side of the Rhine. However, their promising advance into Germany soon slowed down. Pichegru missed a key chance to capture Clerfayt's supply base at the Battle of Handschuhsheim. He had sent two divisions to seize the supply base near Heidelberg. But his troops were attacked at Handschuhsheim, a suburb of Heidelberg. Austrian cavalry, led by Johann von Klenau, charged the French troops as they moved through open fields. The Austrians first defeated the French cavalry, then attacked the foot soldiers. The French division was badly beaten, and their general was captured.

Clerfayt then gathered his troops against Jourdan. He defeated Jourdan at the Battle of Höchst in October. This forced most of Jourdan's army to retreat to the west side of the Rhine. Wurmser then focused on Mannheim. His 17,000 Austrian troops fought Pichegru's 12,000 French soldiers outside the Mannheim fortress. Wurmser drove them from their camp. The French either went into Mannheim city or fled to other forces. Wurmser then began to besiege the French troops inside the city walls.

While Wurmser besieged Mannheim, at Mainz, an Austrian army of 27,000, led by Clerfayt, launched a surprise attack on October 29, 1795. They attacked four divisions (33,000 men) of the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle. The French division on the far right side fled, forcing the other three divisions to retreat. They lost their siege artillery and many soldiers.

On November 10, 1795, Clerfayt defeated Pichegru at the Battle of Pfeddersheim. The French continued to pull back. Clerfayt advanced with 75,000 Austrian troops south along the west bank of the Rhine. They moved against Pichegru's 37,000-man defenses near Worms. At the Battle of Frankenthal (November 13–14, 1795), an Austrian victory forced Pichegru to give up his last defensive position north of Mannheim. Once the French troops at Pfeddersheim left their position, the French forces at Mannheim were trapped. On November 22, 1795, after a one-month siege, the 10,000-strong French garrison surrendered. This event ended the 1795 campaign in Germany.

What Was Learned from the Campaign?

In January 1796, Clerfayt and the French agreed to a ceasefire. The Austrians kept control of many areas on the west side of the Rhine. Even with the ceasefire, both sides continued to plan for war. On January 6, 1796, Lazare Carnot, one of the five French directors, again said that Germany was more important than Italy for the war. France's finances were in bad shape. So, its armies were expected to invade new lands and live off what they found there, just as they had in 1795. Knowing that the French planned to invade Germany, the Austrians announced on May 20, 1796, that the truce would end on May 31. They prepared for war.

Historians believe that the Austrians learned from the campaigns of 1794 and 1795. They realized they could not always rely on their allies. For example, when the Bavarian soldiers at Mannheim quickly surrendered, they gave up all their supplies and weapons. This seemed to confirm to the Austrian commanders that their allies were not dependable. By 1795, the Austrian forces were better prepared to fight alone. They put experienced commanders like Wurmser and Clerfayt in charge of their own armies. After 1795, they learned even more. They combined forces where possible along the Rhine. The Austrian military prepared for 1796 by bringing new recruits from different parts of the empire into their army.

A School for Future Leaders

Historians generally agree that the French campaign of 1795 was a complete disaster. The poor performance of the French might have been linked to Pichegru's possible secret actions. By 1795, Pichegru was leaning towards supporting the French monarchy. He took money from a British agent and was in contact with people who wanted the monarchy to return. The Directory kept him in command of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle until March 1796, when he resigned. He returned to Paris and was welcomed by the public. General Jean Victor Marie Moreau replaced him as army commander. Historians still debate if Pichegru's secret actions, his poor leadership, or the unrealistic plans from Paris caused the French failure.

Even a poorly run campaign can offer lessons for the future. In the campaigns of 1795 and 1796, young officers gained valuable experience for later battles in the Napoleonic wars. Historian Ramsey Weston Phipps said that the 1795 operations were "most interesting" for studying both bad and skillful campaigns. He noted that Jourdan's actions were sensible, but Pichegru's were like a "nightmare." The plans from the Directory were like a "farce."

The training these young officers received in the early years of the war was very important. It helped them learn how to lead under tough conditions, like shortages of soldiers, poor training, and lack of supplies. They also had to deal with confusing tactics and interference from the government. Many future famous generals, known as Marshals of the Empire under Emperor Napoleon I, gained experience in these campaigns. These included Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier, Michel Ney, and Jean de Dieu Soult. This period was truly a "School for Marshals."

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |