SS William A. Irvin facts for kids

SS William A. Irvin in Minnesota Slip

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner | US Steel |

| Builder | American Ship Building Company |

| Yard number | 811 |

| Launched | 10 November 1937 |

| Sponsored by | Gertrude Irvin |

| Maiden voyage | 25 June 1938 |

| In service | 1938 |

| Out of service | 1978 |

| Identification | IMO number: 5390137 |

| Status | Museum ship |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Laker |

| Tonnage | 8,240 gross; 6,072 net |

| Length | 610 ft 9.75 in (186.1757 m) |

| Beam | 60 ft (18 m) |

| Depth | 32 ft 6 in (9.91 m) |

| Installed power | DeLaval Cross steam turbine |

| Speed |

|

| Capacity | 14,000 tons |

|

William A. Irvin (freighter)

|

|

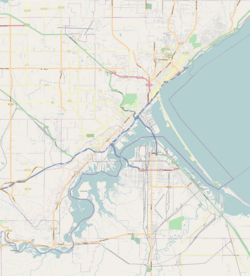

| Location | Minnesota Slip in Duluth Harbor, Duluth, Minnesota |

| Area | Less than one acre |

| Built | 1938 |

| Built by | American Ship Building Company |

| Architectural style | Steel bulk freighter |

| NRHP reference No. | 89000858 |

| Added to NRHP | July 13, 1989 |

The SS William A. Irvin is a large ship called a lake freighter. It was named after William A. Irvin, a important person at US Steel. This ship carried huge amounts of materials like iron ore across the Great Lakes.

The William A. Irvin was the main ship of the US Steel fleet from when it was built in 1938 until 1975. After that, it continued to work hard until it stopped sailing in 1978.

Today, the ship is a museum ship in Duluth, Minnesota. It has been carefully restored and shows what a classic "laker" ship looked like. It's a great example of a "straight decker" because it didn't have a special system to unload itself.

The ship is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This means it's an important historical site. It was recognized in 1989 for its role in shipping on the Great Lakes and its cool design.

There's even a race named after the ship! Every year since 1994, during the Grandma's Marathon weekend, about 2,000 runners take part in the William A. Irvin 5K race. It starts and finishes right by the ship's bright red hull.

Contents

Building and Early Life of the Ship

The SS William A. Irvin was built in Lorain, Ohio. It was launched on November 21, 1937. Its first trip began on June 25, 1938. The William A. Irvin was the first of four similar ships. The other three were named Governor Miller, John Hulst, and Ralph H. Watson. Each ship cost about $1.3 million.

William Irvin's wife, Gertrude Irvin, officially named the ship. The William A. Irvin and its sister ships had many new technologies for their time. They were very good at their job. The William A. Irvin also carried many special guests for US Steel. These guests enjoyed the ship's fancy rooms.

The ship worked for the Pittsburgh Steamship Division of US Steel its whole life. It was one of the few Great Lakes ships that still held a cargo record when it retired in 1978. It was retired because US Steel added a much larger ship to its fleet.

The Ship Becomes a Museum

The William A. Irvin stayed parked in West Duluth for eight years. Then, the Duluth Entertainment Convention Center bought it for $110,000. They wanted it as an attraction for their convention center. The ship was repainted and prepared for its new life. It then moved to its final spot near the Aerial Lift Bridge.

In September 2018, the ship was moved across the bay to Fraser Shipyards in Superior, Wisconsin. This was so environmental work could be done in its home dock. On August 1, 2019, it was put into a dry dock. This allowed workers to paint and fix the parts of the hull that are usually underwater.

The ship was towed back across the harbor on October 16, 2019. It returned to its home behind the Minnesota Slip Bridge.

What the William A. Irvin Looks Like

The SS William A. Irvin is about 610 feet 9.75 inches (186.1757 m) long. It is 60 feet (18 m) wide and 32 feet 6 inches (9.91 m) deep. It could carry about 13,600 tons of cargo.

The William A. Irvin was special because it had a three-story cabin at the front. Most other ships only had two stories. The extra deck had four guest rooms and a lounge for visitors. There was also a special dining room for guests. This dining room was located where a cargo hatch would normally be.

These guest areas were decorated with beautiful oak wood and shiny walnut. They also had brass railings. The William A. Irvin and its sister ships were among the first to use DeLaval Cross steam turbines for power. Older ships used different types of engines.

Much of the William A. Irvin was built using welding. It was also one of the first ships where crew members could go to all parts of the ship from the inside. This meant the crew could stay warm and safe during bad weather. All parts of the William A. Irvin, from the fancy wood to the brass in the engine room, have been kept in excellent condition.

Who Was William A. Irvin?

William A. Irvin was the fourth president of US Steel. He was also the chairman of the company's board. He was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania. William had to leave school after eighth grade because his father passed away. He got a job as a telegraph operator for the Pennsylvania Railroad to help his family. He later worked as a shipping clerk for the same railroad.

In 1895, Irvin started working in the steel industry. He was a shipping clerk for Apollo Steel Company. This company later joined with the American Sheet and Tin Plate Company. By 1904, Irvin was an assistant to the Vice President. He became Vice President of Operations from 1924 to 1931. Then, in 1931, Irvin joined United States Steel Corp. He became president of USS in 1932 and Vice-Chairman of the board in 1938.

Irvin married Luella May Cunningham. They had five children. After Luella passed away, Irvin married Emma Gertrude Gifford in 1910. His namesake ship, the William A. Irvin, was launched in 1938. William and Gertrude were the very first guests to sail on it.

How the Ship Carried Cargo

The William A. Irvin could carry up to 14,000 tons of cargo. This was usually iron ore, either in its raw form or as processed taconite. About 90% of what it carried was taconite. Sometimes, it also carried coal and limestone.

The ship had 18 hatches on its deck. These were openings where cargo was loaded and unloaded. Most of the hatches had large, one-piece steel covers. Each cover weighed 5.5 tons. A special crane lifted these covers off so cargo could be put into the three large holds below. Loading cargo usually took 3 to 4 hours.

The two hatches at the very front of the ship were different. They were older sliding types. This was because the guest dining room was in the way of the hatch crane. To unload cargo, large machines called Hulett cranes were used. These cranes reached into the holds and grabbed 10 to 15 tons of material at a time.

After the cargo was loaded or unloaded, the hatch covers were put back. They were then clamped down tightly. Even though the covers were heavy, they needed to be secured. This kept them from being moved by big waves during storms.

Inside the Engine Room

The William A. Irvin is powered by steam-turbine engines. These are different from the very tall, older engines used in other ships. The steam comes from a boiler room at the front of the engine room. This boiler burns coal, which drops down from a coal storage area above. The ship could carry up to 266 tons of coal.

Special machines called Firite spreaders burn about 1.2 tons of coal every hour to make the steam. This steam goes into the first turbine, which spins a shaft very fast. A special gear then slows this down to turn the propeller at 90 rotations per minute. A second turbine uses leftover steam to get even more power.

Together, these engines produce 2,000 horsepower (1,500 kW). This power moved the William A. Irvin across the lakes at about 11.1 mph (9.6 kn; 17.9 km/h) when it was full of cargo. When empty, it could go a bit faster, about 12.5 mph (10.9 kn; 20.1 km/h). This made it the slowest ship in its fleet.

The crew used two main ways to talk to each other. One was the Chadburn telegraph. This sent signals from the pilothouse to the engineers, telling them how fast to turn the propeller. The other was sound-powered telephones. These phones didn't need electricity and were useful for talking to other parts of the ship, especially during power outages.

See also

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |