Scottish Agricultural Revolution facts for kids

The Agricultural Revolution in Scotland was a time of big changes in how farming was done. It started in the 1600s and kept going into the 1800s. Before this, Scotland's farming was quite old-fashioned. But these changes helped it become one of the most modern and productive farming systems in Europe!

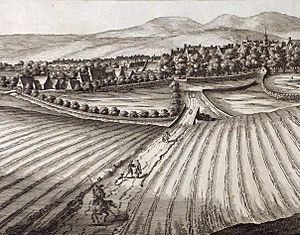

In the past, Scottish farms often used a system called runrig. This system probably started a long, long time ago in the Middle Ages. Imagine a small group of families living in a village called a fermetoun (in the lowlands) or a baile (in the highlands). They would work together on open fields and share grazing land for their animals. With runrig, families would get different small strips of land, called "rigs," to farm each year. This meant their plots were mixed up all over the field.

Contents

How Farming Changed

Farming Before the Revolution (1600s)

Before the 1600s, it was hard to travel in Scotland because of the mountains and bad roads. So, most villages had to grow their own food. They often didn't have much extra if a year was bad. Most farms were small villages where a few families worked together. They used the runrig system, where land was divided into strips.

Farmers used heavy wooden plows with iron blades, pulled by strong oxen. Oxen were good for the tough Scottish soil and cheaper to feed than horses. People who owned land were called husbandmen or landholders. Below them were cottars, who were workers. Cottars often shared common land for grazing animals and worked for others. There were also grassmen who only had rights to graze their animals. In 1695, new laws made it possible to divide up the runrig lands and common areas.

New Ideas and Improvements (1700s)

After Scotland and England joined together in 1707, rich landowners wanted to make farming better. In 1723, a group called the Society of Improvers was started. It had about 300 members, including important people like dukes and landlords.

At first, these changes only happened on some farms in East Lothian and on the lands of a few keen people like John Cockburn and Archibald Grant. Not everyone succeeded; John Cockburn even went bankrupt! But the idea of improving farming spread among the wealthy.

New things were brought in, like the English plow and different types of grass, such as rye grass and clover. Farmers started growing new crops like turnips and cabbages. They also began to enclose fields with fences or walls, drain wet marshy areas, and add lime to the soil to make it better. New roads were built, and trees were planted. Farmers learned new ways to plant seeds in rows (drilling) and to rotate their crops, which means growing different crops in the same field each year to keep the soil healthy.

The potato was brought to Scotland in 1739, and it became a very important food for many people. As fields were enclosed, the old runrig system and shared grazing land started to disappear. Farms also began to specialize: the Lothians became known for growing grain, Ayrshire for raising cattle, and the Borders for sheep.

However, these changes also had a tough side. Many cottars and tenant farmers, whose families had lived on the same land for hundreds of years, had to leave. This is sometimes called the Lowland Clearances. Some landowners built new villages for these displaced workers, but many had to move to cities or even leave Scotland entirely.

More Changes and Challenges (1800s)

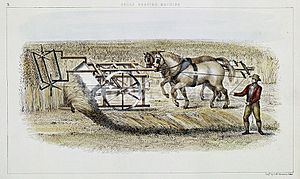

Farming continued to improve in the 1800s. New inventions appeared, like the first working reaping machine, which was developed by Patrick Bell in 1828. Another inventor, James Smith, found a way to improve drainage deep in the soil without disturbing the top layer. This meant that low-lying, wet lands that couldn't be farmed before could now be used for crops. This is why much of the Scottish Lowlands looks so flat and even today.

While farming in the Lowlands changed a lot, the Highlands faced different challenges. Many Highland landowners were struggling financially. They started to change their traditional farming methods, which often involved shared labor, to the Lowland system, which required less labor. This led to the Highland Clearances.

A few very powerful families owned huge parts of Scotland. By 1878, just 68 families owned almost half the land! After the big wars with France ended (1790–1815), these landowners needed money to keep up their fancy lifestyles. So, they started demanding rent in cash instead of keeping the old family-like relationships with their tenants.

The Highland Clearances meant that many tenants were forced off their land as it was enclosed, mainly to make space for sheep farms. These clearances were part of bigger changes happening across the UK, but they were especially harsh in the Highlands. This was because there wasn't much legal protection for tenants, and the change from the old clan system was very sudden. As a result, many people left the land. They moved to cities, or even further away to England, Canada, America, or Australia.

What Happened Next

Because of the Lowland and Highland Clearances, many small villages were broken up. The people who lived there were forced to move. Some went to new villages built by landowners, like Ormiston (built by John Cockburn) or Monymusk (built by Archibald Grant). These new villages were often on the edge of the new, larger farms. Others moved to growing industrial cities like Glasgow, Edinburgh, or cities in northern England. Tens of thousands of people also moved to Canada or the United States, hoping to own their own land there.

In the Highlands, many who stayed became crofters. These were people who lived on very small rented farms with no fixed end date for their tenancy. They used these small farms to grow crops and raise animals. To earn extra money, these families often collected kelp (seaweed), fished, spun linen, or joined the army.

See also

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |