Shubenacadie Indian Residential School facts for kids

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was a boarding school in Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. It was part of a system of schools for Indigenous children in Canada. This school operated from 1930 to 1967. It was the only one of its kind in the Maritimes region. Children from all over the Maritimes were sent there.

The Canadian government's Department of Indian Affairs and the Catholic Church helped fund these schools. About 10% of Mi'kmaq children lived at the Shubenacadie school. Over its 37 years, more than 1,000 children were placed in this institution.

Contents

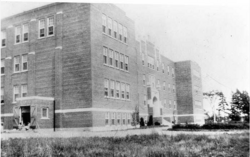

Building the School

Construction of the school began in 1928. It was built on farm land bought from George Gay. This was the only residential school in the Maritimes run by the Canadian government. The school was meant to be staffed by the Roman Catholic group called the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul.

At first, the school's goal was to educate orphans or neglected children from Indigenous reserves. However, just before it opened, the government changed its plan. Duncan Campbell Scott from the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs decided it would also be an option for children who attended small day schools on reserves.

The school opened for staff in May 1929. It was planned to educate 150 students. The first children arrived on February 5, 1930. From 1929 to 1956, the school was managed by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth. From 1956 until it closed in 1967, the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate ran the school.

School Funding and Conditions

For its first 20 years, the government did not give enough money to the school. This meant the poor living conditions found on reserves also existed at the school. The building was often cold and had leaks. Teachers were paid less than half of what teachers in public schools earned.

This lack of funding also led to children often being hungry and not getting enough healthy food. In 1945, a researcher said the nutrition at the school was "overwhelmingly poor." Another researcher the next year called the situation "utterly disgusting."

In 1950, teachers' salaries doubled, almost matching those in public schools. Even with better pay, teachers often stayed only 2 or 3 years. In 1965, 30% of the teachers left. In 1956, when the fourth principal arrived, the food situation improved.

Life as a Student

Many people who attended the school in its early years have shared their difficult experiences. They often talk about serious problems at the school. These included poor living conditions, physical punishments, too many students in one space, and not enough focus on school lessons. Children were also forced to do farm work. They often felt hungry and were taught a curriculum that was unfair and racist. They were punished for speaking their Mi’kmaq language.

William Henry, a survivor, said that in the first few days, children had to learn quickly. He explained, "Otherwise you’re gonna get your head knocked off. Anyway, you learned everything. You learned to obey. And one of the rules that you didn’t break, you obey, and you were scared, you were very scared."

The school received money based on how many children were there. To get more money, they increased the number of students. The school was built for 125 students. However, in the first year, 146 children were placed there. By 1938, there were 175 children. In 1957, there were 160 students in four classrooms. An inspector noted that children needed "much more individual attention." In the 1960s, the average was 123 students per year. In 1968, it was 120, and in its final year, it dropped to 60.

Physical Punishment at School

Many Mi’kmaq who went to the school reported that staff used harsh physical punishment, especially in the first 20 years. One Mi'kmaq person said his sister died shortly after being assaulted by staff. In June 1934, 19 boys were severely beaten by the principal for stealing. There were also claims of children being locked in rooms for days.

Chief Dan Francis complained to Indian Affairs in 1931, saying, "I thought that the school was built for Indian children to learn to read and write, Not for slaves and prisoners like a jail." He also mentioned a boy who was beaten so badly he was sick for seven days. Survivor William Herney said he was strapped and had his mouth washed out with soap for speaking Mi'kmaw. This violence reportedly continued until the second principal arrived in 1944.

Learning and Language

At first, the school focused more on farm work than on regular school subjects. In 1936, Indian Agents criticized the school for making children work too much and not learn enough in the classroom. By 1939, only 2 out of 150 students reached Grade 8, even though some had been there for 10 years. By 1944, only 4 out of 146 students reached Grade 6. In 1946, Indian Affairs made a rule that the same amount of time should be spent on work as in public schools. When the second principal came, the school started focusing more on academics and less on farm work.

In 1961, subjects like industrial arts and home economics were removed for children under Grade 7. By 1964, only 9 out of 110 students reached Grade 8. In 1965, a newspaper reported that the average student reached Grade 8, and only 2% went beyond that.

The school's lessons often described Indigenous people in negative ways. They focused on Europeans "discovering" a "New World" and "civilizing" Indigenous people.

Children were not allowed to speak Mi’kmaq. There are stories of children being beaten for not speaking English. A chief protested in a newspaper in 1931, saying that at the school, "everything Indian is to be forever obliterated." When the fourth principal arrived in 1956, staff stopped punishing students for speaking Mi'kmaq.

Rose Salmons, a former nun who taught at the school, said in 2015 that she was not prepared to teach children who had been taken from their homes and needed love. She said, "We certainly didn't have any training for dealing with children who were taken from their homes, and who really needed love." According to Salmons, teachers were told not to show affection to the children.

Families Divided

Sometimes, the school took children even when their parents did not want them to go. Some children were orphans, and some parents chose to send their children. But in other cases, parents were forced to give up their children, similar to how child protection cases happen today.

Children were not allowed to go home for summer break until 1945, even if their parents wanted them to or offered to pay for travel. They were not allowed home for holidays until the mid-1950s. In 1939, some parents came to the school at Christmas to take their children home. The school called the police, and the parents were made to leave without their children. Some children did not see their parents for 9 years.

Many Mi'kmaq children tried to escape the school, but they were usually found and brought back. On July 7, 1937, Andrew Julian escaped and traveled over 400 km to Cape Breton before being caught. One boy, Steven Labobe, ran all the way back to his home on Prince Edward Island, and the principal decided not to force him to return.

When the fourth principal arrived in 1956, children were finally allowed to go home for holidays. By 1960, students were no longer forced to attend the institution.

Residential schools had long-lasting effects on Mi'kmaw families. Genine Paul-Dimitracopoulos shared that learning about the Shubenacadie school helped her understand her own upbringing. She said her mother "never really showed us love when we were kids coming up." She explained that her mother "was never there to console you or to hug you" if she was hurt or cried.

School Closure and What Happened Next

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School closed after 37 years on June 22, 1967. A private owner bought the land, but it was hard to find new uses for the building. The school building was destroyed by fire in 1986. Today, a plastics factory stands on the site. A few staff houses remain, and the road to the school is still called "Indian School Road."

After the school closed, provincial child protection services took over. Many Indigenous children were then placed in foster homes. Even today, Indigenous children are more likely to be taken into care. In 2014, in Nova Scotia, 21.4% of Indigenous children were in care against their parents’ wishes, compared to 4% of children in the general population.

In 1995, Nora Bernard started a group for survivors of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. About 900 Mi’kmaq joined. In 1997, they filed a lawsuit against the government. This led to a large national settlement, which was one of the biggest agreements for historical harm in the world.

In 2012, a monument was put up at the education center on the We’koqma’q First Nation in Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia. This monument remembers the suffering and unfairness caused by the school. Mi’kmaq Grand Chief Ben Sylliboy, who attended the school in 1947, helped unveil the monument. He said it was important to remind people so such a tragedy would not happen again.

Today, efforts are being made to keep the Mi’kmaq language alive. In 2014, 55% of Mi’kmaq homes used at least some Mi’kmaq language. 33% of children could speak the language.

The Nova Scotia government and the Mi’kmaq community created the Mi’kmaq Kina’ matnewey. This is considered the most successful First Nation Education Program in Canada. In 1982, the first Mi’kmaq-run school opened in Nova Scotia. By 1997, Mi’kmaq communities on reserves were in charge of their own education. There are now 11 schools run by First Nations bands in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia now has the highest rate of Indigenous students staying in school in the country. More than half of the teachers are Mi’kmaq. From 2011 to 2012, there was a 25% increase in Mi’kmaq students going to university. Atlantic Canada has the highest rate of Indigenous students attending university in the country.

Notable Mi’kmaq who attended the school

- Rita Joe

- Nora Bernard

- Grand Chief Ben Sylliboy

- Isabelle Knockwood

- Noel Knockwood

- Noel Doucette (1945–51) – He helped lead the way for the school's closure in 1967.

See also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |