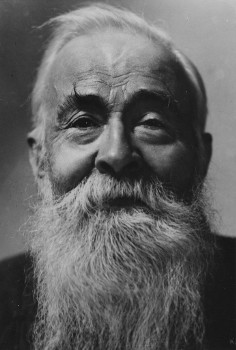

Sir Edmund Backhouse, 2nd Baronet facts for kids

Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse (born October 20, 1873 – died January 8, 1944) was a British scholar who studied Asian cultures, especially China. He was also a linguist, meaning he spoke many languages. His books were very important in how people in the Western world saw the last years of the Qing dynasty, which was China's last ruling family (1644–1912).

However, after he died, it was discovered that a main source for one of his books, China Under the Empress Dowager, was a fake. It seems Backhouse himself probably created this fake source. His biographer, Hugh Trevor-Roper, said Backhouse was a "confidence man," someone who tricked many people, including the British government and Oxford University. Another editor, Derek Sandhaus, believes Backhouse's personal stories, called Décadence Mandchoue, are also made up but might contain some real details.

Early Life and Education

Edmund Backhouse was born into a Quaker family in Darlington, England. Many of his relatives were scholars and church leaders. In 1918, he inherited the title of baronet from his father, Sir Jonathan Backhouse. His younger brother, Sir Roger Backhouse, became a very important naval officer.

Backhouse once wrote that his childhood was difficult. He felt his wealthy parents were unhappy and didn't show him much kindness. He went to Winchester College and then Merton College, Oxford. While at Oxford, he had a tough time in 1894. He returned to the university in 1895 but never finished his degree. He left the country because he had gotten into a lot of debt.

Life and Work in China

In 1899, Edmund Backhouse arrived in Peking, China. He soon started working with George Ernest Morrison, a writer for The Times newspaper. Backhouse translated Chinese works into English for Morrison, as Morrison could not read Chinese. Backhouse claimed to have secret information about the Chinese imperial court. However, there is no real proof that he knew anyone important there.

By this time, Backhouse had learned several languages, including Russian, Japanese, and Chinese. He lived in Peking for most of his life. He worked for different companies and people, using his language skills and supposed connections to the Chinese court. He tried to help them make business deals, but none of these deals ever worked out.

In 1910, he published a history book called China Under the Empress Dowager. In 1914, he published Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking. He wrote both books with British journalist J.O.P. Bland. These books helped him become known as an important scholar of Asian studies.

From 1913 to 1923, Backhouse gave many Chinese manuscripts to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. He hoped this would help him get a teaching job there, but it did not happen. He donated a huge amount of manuscripts, about eight tons in total. Some of these were later found to have questionable origins. Still, he gave over 17,000 items, and some were very valuable. This included rare volumes of the Yongle Encyclopedia from the 15th century. The Library called his gift "one of the finest and most generous gifts in the Library's history."

During the First World War, Backhouse also worked as a secret agent for the British government in China. He tried to arrange a deal for weapons between China and the UK. In 1916, he pretended to represent the Chinese Imperial Court. He then made two fake deals with the American Bank Note Company and John Brown & Company, a British shipbuilding company. Neither company received any confirmation from the court. When they tried to contact Backhouse, he had left China. After he returned to Peking in 1922, he refused to talk about these deals.

Backhouse's life often switched between living alone and working for Western companies or governments. In 1939, he met Richard Hoeppli, a Swiss consul. Hoeppli convinced him to write his life story. Backhouse's memoirs, Décadence Mandchoue, were published in 2011. Another memoir about his early life, The Dead Past, came out in 2017.

During World War II, Peking was controlled by Imperial Japan. Britain was at war with Japan from 1941. By then, Backhouse supported the Axis powers and hoped they would win the war and defeat Great Britain. Backhouse died in Peking in 1944 at age 70. He was not married. He had become a Catholic in 1942 and was buried in a Catholic cemetery. Even though he supported the other side in the war, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission listed him among British civilians who died in China during the war.

Claims of Fake Information

There are two main accusations against Backhouse regarding his work.

One accusation is about his book China Under the Empress Dowager. Backhouse claimed that much of the book was based on the diary of a high court official named Ching-shan (景善). Backhouse said he found this diary in Ching-shan's house after the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.

However, scholars have questioned if this diary was real. George Ernest Morrison doubted it, and later, J. J. L. Duyvendak, who first defended it, changed his mind in 1940. In 1991, Lo Hui-min proved that the diary was definitely a fake.

In 1973, historian Hugh Trevor-Roper received Backhouse's personal writings. In these writings, Backhouse also claimed to have met famous people like Leo Tolstoy and acted with Sarah Bernhardt.

Derek Sandhaus, who edited Backhouse's memoirs, noted that Trevor-Roper did not ask Chinese experts for their opinion. Sandhaus believes that while Backhouse made up many stories, some details might be true or were confirmed by others. Backhouse spoke Chinese, Manchu, and Mongolian, which were the languages of the imperial household. So, his descriptions of the court's atmosphere might be more accurate than Trevor-Roper thought.

Works

- China under the empress dowager

- Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |