Sirenik language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sirenik |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Сиӷы́ных | ||||

| Pronunciation | IPA: [siˈʁənəx] | |||

| Native to | Russia | |||

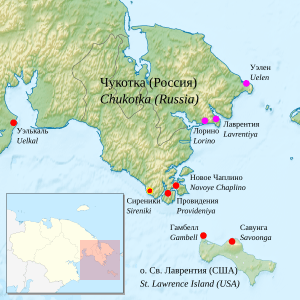

| Region | Bering Strait region, mixed populations in settlements Sireniki and Imtuk | |||

| Ethnicity | Sirenik Eskimos | |||

| Extinct | 1997e18 with the death of Valentina Wye |

|||

| Language family |

Eskimo–Aleut

|

|||

| Writing system | Transcribed with Cyrillic in old monographs (extended with diacritics), but new publications may appear also romanised | |||

|

||||

Sirenik Yupik (also called Old Sirenik or Vuteen) was a language spoken by the Sirenik Eskimos. It was part of the Eskimo–Aleut language family. People spoke it in and around the village of Sireniki in Chukotka Peninsula, Russia.

Sadly, the Sirenik language is now extinct. The very last person who spoke it as their native language, a woman named Vyjye (Valentina Wye), passed away in January 1997. Today, all Sirenik Eskimos speak either Siberian Yupik or Russian.

The people of Sireniki called their language Сиӷы́ных (Si-GHUH-nuhkh). They called themselves сиӷы́ныгмы̄́ӷий (Si-GHUH-nuhkh-muh-GHEE-y), which means "Sirenikites."

Contents

What Kind of Language Was Sirenik?

How Sirenik is Related to Other Languages

Some experts believe Sirenik was a unique branch of the Eskimo language family, separate from Yupik and Inuit. Others think it was part of the Yupik family. The exact family tree of Sirenik is still a topic of discussion among linguists.

Sirenik was quite different from other Eskimo languages. Many of its words came from completely different roots. Its grammar also had special features. For example, most Eskimo languages have a "dual number" for two items, but Sirenik only had singular (one) and plural (many). These differences meant that Sirenik speakers could not easily understand their closest language relatives. Because of this, Sirenik Eskimos often used the Chukchi language to talk with neighboring Eskimo groups. This might be because Sirenik speakers lived separately from other Eskimo groups for a long time.

How Sirenik Words Are Built

Sirenik was a polysynthetic language. This means that words are often very long and can include many parts (suffixes) that add meaning. It's like building a long train where each car adds a new idea to the main engine. This allows a single word to express what might be a whole sentence in English!

How Sirenik Sounds Were Made

Sirenik had its own set of unique sounds, including different consonants and vowels. These sounds helped make it distinct from other languages.

How Sirenik Words Changed Meaning

Like other Eskimo languages, Sirenik had a complex way of changing words to add meaning. This is called morphology.

Nouns and Verbs in Sirenik

In Sirenik, nouns (words for people, places, things) and verbs (action words) shared some similar features in how they changed. For example, the way you showed who owned something (like "my dog") was similar to how you showed who was doing an action (like "I see").

Common Grammar Rules

Some grammar rules, like showing who is doing something (person) and how many are doing it (number), applied to both nouns and verbs.

Person in Sirenik

Sirenik could tell the difference between "himself/herself" and "another person." So, a word could mean "He sees his own dog" or "He sees another person's dog." This is like using "reflexive pronouns" in English (like "himself").

Number in Sirenik

Unlike many other Eskimo languages, Sirenik only had two numbers: singular (for one thing) and plural (for more than one). It did not have a "dual" number for exactly two things. This was a special feature of Sirenik.

Turning Nouns into Verbs

You could turn a noun into a verb by adding a suffix. For example, adding the suffix -ɕuɣɨn- to a noun meant "to be similar to" that noun.

- If you had the word for "raven," you could add -ɕuɣɨn- to make it mean "to be similar to a raven."

Describing Nouns with Verbs

Sirenik could also turn a noun into a verb that described it. For example, adding -t͡ʃ ɨ- to the word for "man" could make it mean "to be a man."

- So, "you are a man" or "he/she is a man" could be single words.

Verbs from Place Names

You could even make verbs from place names!

- From the place name Imtuk, you could make a verb like "I travel to Imtuk."

How Nouns Changed in Sirenik

Nouns in Sirenik changed their endings to show their role in a sentence (like who owns them or where they are). This is called declension. Sirenik used many different endings for this.

For example, the word for "child" (taŋaχ) would change its ending depending on if it was "my child," "your child," "from my child," or "to my child." This shows that Sirenik was an agglutinative language, where many small parts are added to a word.

Sirenik did not have grammatical gender, meaning nouns were not "masculine" or "feminine" like in some other languages.

Cases in Sirenik

Sirenik used different "cases" to show a noun's job in a sentence. It had many cases, including:

- Absolutive: For the main subject of a sentence.

- Relative: Used for both showing who owns something and who is doing an action.

- Ablative / Instrumental: Showing "from" or "with."

- Dative / Lative: Showing "to" or "for."

- Locative: Showing "at" or "in."

- Equative: Showing "like" or "as."

How Verbs Changed in Sirenik

Verbs in Sirenik also had many endings that changed their meaning. These endings could show the mood of the verb (like a command or a question), if it was negative, when it happened (tense), and who was doing the action or who the action was done to.

For example, a single verb could mean "I lead you" or "Let me lead you." Another could mean "Don't you see me?"

Because of all these endings, Sirenik verbs could become very long and carry a lot of meaning, sometimes even a whole sentence's worth!

Grammatical Categories for Verbs

The way Sirenik verbs were built allowed them to express many different ideas.

Showing Negation

You could make a verb negative by adding a suffix.

- "The man walks" could become "The man does not walk" just by adding an ending to the verb.

Showing How an Action Happens

Suffixes could also show how an action happened, like if it was done "slowly."

- "To work" could become "to work slowly" by adding a suffix.

Showing What You Want to Do

Sirenik didn't have separate words like "want to" or "wish to." Instead, it added suffixes to verbs.

- "To work" could become "to want to work" by adding the suffix -jux-.

Showing Different Voices

Sirenik verbs could also show different "voices," like:

- Active: "He takes something."

- Passive: "Something is taken."

- Causative: "He makes someone go."

All these were expressed by adding suffixes to the verb.

Participles in Sirenik

Sirenik used "participles," which are special forms of verbs that act like adjectives or adverbs. They helped connect different parts of a sentence.

Adverbial Participles

These participles acted like adverbs, telling you more about the main action. They could show things like:

- Reason or Purpose: Why something happened.

- Timing: When something happened (e.g., "after" or "while").

- Conditions: If something happened (e.g., "if I were a marksman...").

An interesting thing about these participles is that the person doing the "dependent action" (the action in the participle) didn't have to be the same person doing the "main action" of the sentence.

Adjectival Participles

These participles acted like adjectives, describing nouns.

- For example, "The sledge [that went to Imtuk] returned." Here, "that went to Imtuk" describes the sledge.

- They could also show "ability," like "able to." So, "A child who is able to walk moves around spontaneously."

How Sirenik Sentences Were Put Together

Ergative–Absolutive Structure

Sirenik, like many Eskimo languages, had an ergative–absolutive structure. This is a special way of organizing who is doing what in a sentence, especially when there's an action being done to something. It's different from how English works.

Using Third Person Endings

Sirenik had special endings for "third person" (he, she, it, they). It could tell the difference between someone doing something to "themselves" versus doing something to "another person." This helped make sentences very clear.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Idioma sirenik para niños

In Spanish: Idioma sirenik para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |