Structural color facts for kids

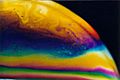

Structural coloration is a special way that some animals and plants get their amazing colors. Instead of using colored chemicals called pigments (like paint), these colors come from the tiny shapes and structures on their surfaces. Think of it like a tiny, invisible pattern that plays with light!

Sometimes, structural coloration works with pigments. For example, a peacock's tail feathers have brown pigment. But the tiny structures on the feathers make them look bright blue, green, and turquoise. These colors can also look shimmery and change as you move, which is called iridescence.

Contents

How Colors Appear Without Pigments

The colors you see from structural coloration are made when light hits very small, organized structures. These structures are often thinner than a human hair! When light waves hit these tiny shapes, they bounce off and interact with each other. This interaction is called wave interference.

Light and Tiny Structures

Imagine light as tiny waves. When these waves hit the special structures, some waves bounce off the top, and some go through and bounce off a layer underneath. When these bounced waves meet, they can either join up and become stronger (making a bright color) or cancel each other out (making no color).

Why Colors Change

The way these light waves interact depends on the angle you are looking from and the thickness of the tiny structures. This is why a peacock's feathers can look different colors as it moves. It's like magic, but it's all science!

Who Discovered Structural Coloration?

The first people to notice structural coloration were English scientists Robert Hooke and Isaac Newton. They saw it in things like peacock feathers way back in the 1600s.

Early Observations

- In 1665, Robert Hooke wrote about his observations in a book called Micrographia. He was one of the first to describe how these colors appeared.

- Isaac Newton also studied how light worked and noticed these special colors.

Explaining the Science

About a century later, another scientist named Thomas Young explained how structural coloration works. He called the principle "wave interference." He showed that the colors come from light waves bouncing off very thin layers and interfering with each other.

Examples in Nature

Structural coloration is found all over nature, creating some of the most beautiful and striking colors we see.

Birds

Many birds have bright feathers thanks to structural coloration.

- The European bee-eater has brilliant colors partly because of tiny structures in its feathers that act like tiny prisms.

- The male Parotia lawesii bird of paradise uses his breast feathers, which can switch from blue to yellow, to attract females.

Insects

Insects are also masters of structural color.

- The brilliant green of the emerald swallowtail butterfly (Papilio palinurus) comes from microscopic bowl-shaped structures that reflect yellow light directly and blue light from their sides.

- The iridescent scales of the Lamprocyphus augustus weevil contain tiny crystal structures that reflect light in all directions, making it look uniformly green.

Other Animals

- Some golden moles, like Chrysospalax, have thick fur that gets its color from structural effects.

- The blue rings on the Hapalochlaena lunulata (blue-ringed octopus) are also created by structural coloration.

- The hollow nanofibre bristles of the Aphrodita aculeata (a type of sea mouse) reflect light in yellows, reds, and greens to warn away predators.

Plants

- The Pollia condensata berries have the most intense blue color known in nature, all thanks to structural coloration.

Images for kids

-

Robert Hooke's 1665 Micrographia contains the first observations of structural colours.

-

In 1892, Frank Evers Beddard noted that Chrysospalax golden moles' thick fur was structurally coloured.

-

Electron micrograph of a fractured surface of nacre showing multiple thin layers.

-

Magnificent non-iridescent colours of blue-and-yellow macaw created by random nanochannels.

-

One of Gabriel Lippmann's colour photographs, "Le Cervin", 1899, made using a monochrome photographic process (a single emulsion). The colours are structural, created by interference with light reflected from the back of the glass plate.

-

European bee-eaters owe their brilliant colours partly to diffraction grating microstructures in their feathers.

-

The male Parotia lawesii bird of paradise signals to the female with his breast feathers that switch from blue to yellow.

See also

In Spanish: Coloración estructural para niños

In Spanish: Coloración estructural para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |