Susanna Centlivre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Susanna Centlivre

|

|

|---|---|

A mezzotint of Susanna Centlivre by Peter Pelham (1720) originally painted by D. Fermin

|

|

| Born |

Susanna Freeman

1669 (baptised) |

| Died | 1 December 1723 |

| Nationality | English |

Susanna Centlivre (born around 1669, died 1 December 1723) was an amazing English writer, actress, and poet. She was born Susanna Freeman and was also known as Susanna Carroll during her career. Many people call her the "most successful female playwright of the eighteenth century." Her plays were so popular that they were still performed long after other writers of her time were forgotten. She became known as one of the most important women in English theater, second only to Aphra Behn.

Contents

Early Life and Acting Career

We don't know a lot about Susanna Centlivre's early life. She was likely born Susanna Freeman in Whaplode, Lincolnshire, England, and was baptized on November 20, 1669. Her father, William Freeman, was a dissenter and supported the Parliament during the English Civil War. This meant her family faced tough times when the monarchy was restored.

It's thought that her father died when she was three. Her mother passed away soon after remarrying, and her stepfather also remarried quickly. This left Susanna on her own at a young age.

There are two main stories about how she started acting and came to London. One story says she was found crying by the roadside by a student named Anthony Hammond. He was so impressed by her that he secretly brought her to his college, disguised as a boy. She stayed there for months, learning grammar and other subjects, before heading to London.

A more likely story is that she joined a group of traveling actors in Stamford. She became very popular playing "breeches roles," where women dressed as men. She was good at these parts, which helped her gain fame.

Marriages and Moving to London

Susanna's acting skills charmed many people. She married her first husband, Mr. Fox, when she was just sixteen, but he died less than a year later. After his death, she is believed to have married an army officer named Carroll, who sadly died in a duel about a year and a half later. She continued to use the name Carroll until her next marriage.

Even though much of her early life is a bit of a mystery, we know that Susanna learned a lot by reading and talking to people. She also knew French well, which helped her with her writing. After her second husband's death, she spent a lot of time in London and started writing to support herself.

By 1706, Susanna Centlivre was becoming known. While performing as Alexander the Great in a play called The Rival Queens at Windsor Castle, she met Joseph Centlivre. He was a cook for Anne, Queen of Great Britain. They got married on April 23, 1707.

The Centlivres moved to Buckingham Court in London around 1712 or 1713. Susanna Centlivre had a long and successful career, writing poems, letters, and, most famously, plays. She passed away on December 1, 1723, due to a serious illness she had since 1719. She was buried three days later in St Paul's, Covent Garden.

Susanna Centlivre's Writings

Susanna Centlivre started writing poetry very young. Her first published works were five letters in May 1700. These letters showed her playful and clever writing style. In July 1700, she published more letters under the name Astrea, a pen name used before by Aphra Behn. This was probably to get more public attention.

She also wrote poetry in her letters with George Farquhar. In September 1700, she contributed a poem called "Of Rhetorick" to a collection honoring the famous writer John Dryden.

First Plays and Growing Fame

In October 1700, Centlivre published her first play, The Perjur'd Husband: or, The Adventures of Venice. This play was performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and was very well received. She proudly published it under her own name, highlighting that a woman wrote it. By the end of 1700, Susanna was well-known in London's literary and acting circles.

Her next play, The Beau's Duel, was performed in June 1702. While it was good, it wasn't on stage for very long. For the next few years, her plays were less successful. She even tried to hide that she was a woman writer for her next two plays, The Stolen Heiress (December 1702) and Love's Contrivance (June 1703).

Her play The Gamester, first performed in February 1705, was a big hit. In this play, she aimed to show the problems with gambling. It was her most successful play at that time and was often performed again in later years.

Centlivre continued to write about gambling in her play The Basset Table, performed in November 1705. After this success, she wrote Love at a Venture, which was performed in 1706.

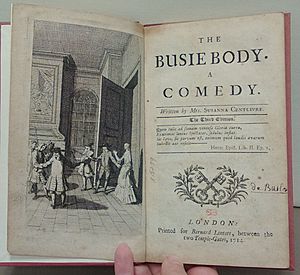

Susanna Centlivre was a very successful professional playwright. Another famous playwright, Colley Cibber, was even accused of using parts of her play Love at a Venture for his own play. After a break following her third marriage, Centlivre wrote her most successful comedy, The Busie Body (May 1709). This play ran for thirteen nights, which was amazing for that time, and was brought back the next season.

Her next play, The Man's Bewitch'd, was performed in December 1709. It made fun of country gentlemen who supported the Tory party. Because this play came out during an election, the Tory newspapers attacked her. They even printed a fake interview where she supposedly blamed actors for her failures. She had to convince the actors that it was a trick.

Later Works and Political Themes

Many of Centlivre's later plays showed her support for the Whig political party and her opposition to the Tory party. She often showed Tory fathers or guardians as obstacles to young lovers' happiness, with the lovers usually supporting the Whigs.

In March 1710, Centlivre released A Bickerstaff's Burying, another political play. She was brave enough to openly support the Hanoverian family becoming the next rulers of England, even if it risked annoying Queen Anne. She also wrote a sequel to her hit play The Busy Body, called Marplot, or, The Second Part of the Busie-Body (December 1710). It wasn't as popular as the first, but it was performed seven times. This sequel also showed her interest in the fight between the Whigs and Tories.

Her play The Perplex'd Lovers (January 1712) showed her political views even more strongly. Many of her plays over the next five years were about helping the Whigs and the House of Hanover. This play wasn't very successful, running for only three nights. The theater managers even banned the ending speech because they feared trouble.

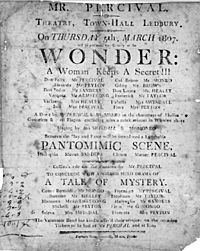

In 1713, Centlivre wrote two poems. One was about the great performance of actress Anne Oldfield. The other, "The Masquerade," was for the French ambassador. Centlivre's next play was The Wonder (April 1714), a comedy. She dedicated it to the Duke of Cambridge, showing her loyalty to the House of Hanover. This was a risky move, but it paid off when the Duke became King George I. The Wonder was a huge hit and was even the play where the famous actor David Garrick gave his last performance in 1776.

Her next two plays, A Gotham Election and A Wife Well Manag'd, were published in 1715. These plays continued her theme of political comedy. They showed how Centlivre was ahead of her time by highlighting social problems in theater.

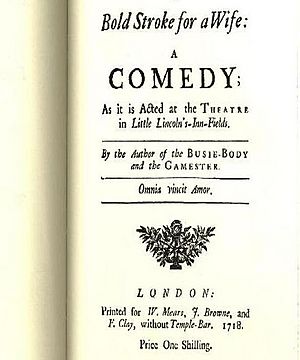

In 1716, she wrote a poem called "Ode to Hygeia" in response to a Whig leader's illness. She followed this with more poems about the political situation. After some attacks from the writer Alexander Pope, she and co-author Nicholas Rowe published her next play, The Cruel Gift (December 1716). This was a heroic drama, and it was well-received, performed seven times that year. In February 1718, Centlivre published A Bold Stroke for a Wife. This funny play was very successful and is considered by some to be her best work. It's the only play she claimed was completely original.

In 1717, Centlivre wrote a poem called "An Epistle from a Lady of Great Britain to the King of Sweden, on the intended Invasion." This was her response to Charles XII of Sweden threatening to attack England. She also wrote two poems for Mr. Rowe (Nicholas) in 1718. One was about visiting her hometown, and the other was a sad poem after Rowe's death, which brought her positive attention.

In 1719, Centlivre became very ill, but she kept writing until her death. She published two more poems in 1720. She also wrote "A Woman's CASE: in an Epistle to CHARLES JOYE, Esq; Deputy-Governor of the South Sea," which talked about her political connections and her relationship with her husband. Her last play, The Artifice, was produced and published in October 1722.

Themes in Her Plays

Susanna Centlivre's plays often showed her positive views on England's political and legal systems. A common theme was the idea of freedom within marriage and for citizens.

Politics in Her Plays

Centlivre sometimes used her plays to talk about politics. She was very against Catholicism, which you can see in some of her play dedications and speeches. For example, in The Wonder, she strongly supported the idea of a Protestant ruler for England. While many of her plays avoided direct party politics, The Gotham Election was clearly political. Some of her more controversial speeches, like one in The Perplexed Lovers, were only published in the play text and not actually spoken on stage, likely to avoid trouble.

Her Comedies

Centlivre is most famous for her comedies. These plays often followed a Spanish style, full of romance and strong feelings like love and jealousy. They often included disguises, talk of duels, and a mix of strong emotions and silly situations. Her best comedies feature smart female characters who are just as clever as the men. Because there was a lot of unfairness against women playwrights, Centlivre sometimes used a fake name or hid her more daring messages.

Her Tragedies

People didn't think as highly of her two tragic-comedies, The Perjur'd Husband and The Stolen Heiress. However, her pure tragedy, The Cruel Gift, was better received. Critics sometimes said the characters in these plays felt a bit flat and the stories weren't very believable.

List of Susanna Centlivre's Works

Plays

Books

|

Poems

|

See also

In Spanish: Susanna Centlivre para niños

In Spanish: Susanna Centlivre para niños

- List of early-modern British women playwrights

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |