The Feminead facts for kids

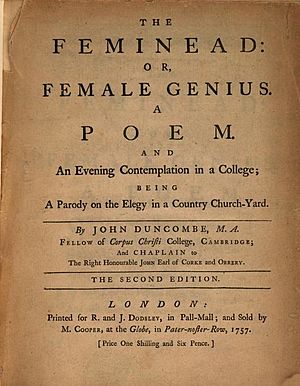

Title page of John Duncombe's The Feminead (1754), 2nd edition (1757)(Google Books)

|

|

| Author | John Duncombe |

|---|---|

| Country | Britain |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | London: M. Cooper (1st edition); R. & J. Dodsley (2nd edition) |

|

Publication date

|

1754; rpt. 1757 |

John Duncombe (1729-1786) wrote a special poem called The Feminead. It was first published in 1754. The poem celebrates talented British women writers. Its title was changed to The Feminead in the second edition, which came out in 1757.

Contents

What The Feminead Is About

This poem is like an essay written in verse. It has 380 lines. Duncombe believed that women are "equally divine" in their minds and looks. He wanted readers to ignore "Prejudice" and instead praise "a sister-choir" of women writers. He also used a nationalistic idea, comparing "free-born" British women to a stereotypical image of women in a "Seraglio" (a place where women were kept in some cultures). He linked these women to famous thinkers from ancient Greece and Rome.

Duncombe also made it clear that he supported women artists who still took care of their family duties. He thought that spending time on art and culture could keep women from less important activities.

But lives there one, whose unassuming mind,

Tho' grac'd by nature, and by art refin'd,

Pleas'd with domestic excellence, can spare

Some hours from studious ease to social care,

And with her pen that time alone employs

Which others waste in visits, cards, and noise;

From affectation free, tho' deeply read,

"With wit well natur'd, and with books well bred?"

With such (and such there are) each happy day

Must fly improving, and improv'd away;

Inconstancy might fix and settle there,

And Wisdom's voice approve the chosen fair.

Duncombe chose certain British women writers to highlight. He quickly passed over some writers from earlier times, like Behn and Centlivre. He focused on writers who were still alive and known for their good morals and artistic skills. Many of the writers he mentioned were connected to the Blue Stockings Society. This was an informal group of women in England who met to discuss education and social topics in the mid-1700s.

Duncombe did not talk about writing as a job that paid money. Instead, he presented it as a hobby or a passion. The Feminead ends by suggesting that women who are encouraged to learn and create make better wives and mothers. This kind of argument, appealing to what readers might find useful, was common in early texts that supported women's roles.

How The Feminead Fit In

Duncombe's poem was popular and well-liked. It was also part of a larger trend. Many people tried to promote women writers as important parts of the country's literary history. This period saw many "female panegyrics," which were writings praising women. Most of these were written by men.

Other works like Duncombe's include:

- George Ballard's Memoirs of British Ladies (1752), which had biographies of 65 important women.

- Theophilus Cibber's Lives of the Poets (1753).

- Poems by Eminent Ladies (1755), an anthology by George Colman and Bonnell Thornton.

- Biographium faemineum: the female worthies (1766), which was written by an unknown author.

In 1774, Mary Scott published The Female Advocate; a poem. Occasioned upon reading Mr. Duncombe's Feminead. In her poem, she thanked Duncombe and wanted to recognize even more writers. She included over fifty women, three of whom Duncombe had already mentioned: Chapone, Philips, and Pilkington. All these writings together show how important women's writing had become by the mid-1700s.

Writers Mentioned in The Feminead

- Aphra Behn (1640–1689)

- Frances Brooke (1724–1789)

- Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806)

- Susannah Centlivre (1669–1723)

- Hester Chapone (1727–1801)

- Catharine Trotter Cockburn (1679–1749)

- Susanna Duncombe (1725–1812)

- Anne Kingsmill Finch (1661–1720)

- Anne Ingram (c. 1696 – 1764)

- Mary Leapor (1722–1746)

- Judith Madan (1702–1781)

- Delarivier Manley (1663 or c. 1670 – 1724)

- Martha Peckard (1729–1805)

- Elizabeth Pennington (1732–1759)

- Katherine Philips (1632–1664)

- Teresia Constantia Phillips (1709–1765)

- Laetitia Pilkington (c. 1709 – 1750)

- Elizabeth Singer Rowe (1674–1737)

- Frances Seymour, Duchess of Somerset (born 1699)

- Frances Anne Vane (c. 1715 – 1788)

- Mehetabel Wesley Wright (1697–1750)

See also

- The Female Advocate

- The feminead: or, female genius (Wikisource)

- Mary Scott

- Women's writing (literary category)

Etexts

- Digitized version of Augustan Reprint Society edition (1981) available at the Internet Archive

- Digitized version of 2nd edition available at Google Books

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |