Catharine Trotter Cockburn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Catharine Trotter Cockburn

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Catharine Trotter 16 August 1679 London, England |

| Died | 11 May 1749 (aged 69) Longhorsley, England |

| Resting place | Longhorsley |

| Occupation | novelist, dramatist, philosopher. |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Genre | correspondence |

| Subject | moral philosophy, theological tracts |

| Spouse |

Patrick Cockburn

(m. 1708) |

Catharine Trotter Cockburn (born August 16, 1679 – died May 11, 1749) was an amazing English writer. She was a novelist, a playwright, and a philosopher. She wrote about important ideas like how we know what's right and wrong. She also wrote many letters and essays about religion.

Catharine believed that people don't just know moral rules from birth. Instead, she thought we can discover them using our God-given ability to reason. In 1702, she published her first big philosophy book. It was called A Defence of Mr. Lock's [sic.] An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. The famous philosopher John Locke was so happy with her defense of his ideas. He even sent her gifts of money and books!

Her work caught the eye of other important people, like William Warburton. He wrote the introduction for her last philosophy book. A biographer named Thomas Birch also asked her to help him collect all her writings. She agreed, but sadly, she passed away before the collection could be printed. Birch later published a two-volume set of her works in 1751. This collection helped people learn about her and her many talents.

Contents

Who was Catharine Trotter?

Catharine Trotter was born in London on August 16, 1679. Both of her parents were from Scotland. Her father, Captain David Trotter, was a high-ranking officer in the Royal Navy. He was even known by King Charles II.

Sadly, her father died in 1684. Her family then faced money problems. Her mother, Sarah Bellenden, was related to important noble families. She received a small pension after her husband's death.

Catharine was the younger of two daughters. Her older sister married a doctor who worked for the army.

How did Catharine learn?

Catharine was very smart from a young age. She loved learning and taught herself to write beautifully. She also enjoyed making up poems on the spot. We don't know much about her formal schooling. But it seems she didn't have much of it.

However, nothing stopped her desire to learn. She read a lot and wrote with great enthusiasm. At first, she read stories and imaginative works. As she grew older, she focused on books about moral philosophy and religion. She taught herself French. With a friend's help, she also learned Latin.

What were her early writings?

Catharine's writing often aimed to teach a lesson. Even her love songs encouraged self-control and good behavior. Because of her father's job and her mother's family, she met many important people. Even though she didn't have much money, she was often invited to the homes of the rich and famous. People admired her beauty and kind manners.

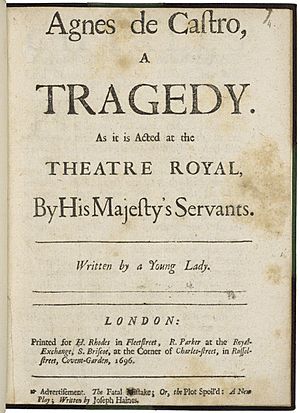

Catharine was very talented and mostly taught herself. Her first novel, The Adventures of a Young Lady, was published anonymously in 1693. She was only 14 years old! Her first play, Agnes de Castro, was performed in 1695. It was printed the next year. This play was based on a French novel translated by Aphra Behn.

In 1696, Catharine was made fun of in a play called The Female Wits. She was shown as "Calista," a lady who pretended to know many languages. The next year, she wrote poems praising William Congreve's play The Mourning Bride. This helped her become friends with him.

In 1698, her second play, Fatal Friendship, was performed. Many people liked it. This play made her famous as a playwright. It also brought her many powerful and fashionable friends.

In 1700, she was one of several Englishwomen who wrote poems about the death of John Dryden. She was praised as a "Muse" by other poets.

In 1701, her comedy Love at a Loss was performed. Later that year, her third tragedy, The Unhappy Penitent, was also performed. Also in 1701, she wrote her Defence of Mr. Locke's Essay of Human Understanding. This book helped her become friends with Locke and Lady Masham. They introduced her to many other important people.

Her religious journey

Catharine was raised Protestant. But she became a Roman Catholic when she was young. She followed this faith for many years. However, her strict fasting made her very sick. In 1703, her doctor told her to stop fasting so much.

Catharine was often unwell. She found it hard to walk far or write by candlelight. But she had amazing energy and determination. She managed to write many books and plays. She also handled all the business of getting her works performed and published.

From 1701 to 1708, Catharine wrote many letters to her friend George Burnet. He traveled a lot and told people about her work. He even got the famous philosopher Gottfried Leibnitz interested in her ideas.

In 1704, Catharine wrote a poem about the Duke of Marlborough's victory at the Battle of Blenheim. The Duke and his family liked it very much. She hoped to get a pension from the King because of her father's service. But she only received a small gift. She wrote another poem for the Duke in 1706.

In 1706, her play The Revolution of Sweden was performed. It was based on the story of Gustavus Ericson.

Catharine often visited her sister and mother in Salisbury. But her favorite place to live was in London. There, she could focus on her writing without distractions. In Salisbury, she met Bishop Gilbert Burnet and his wife, Elizabeth Burnet. Mrs. Burnet became a loving friend to Catharine.

Returning to the Church of England

Catharine always wanted to serve God and help the world. But she changed her mind about how to do this. In 1707, after much study and prayer, she left the Roman Catholic faith. She wrote and published Two Letters concerning a Guide in Controversies. Bishop Burnet wrote the introduction for her book. She gave strong reasons for her change of faith. After this, she remained a loyal member of the Church of England.

Life with Reverend Cockburn

In 1707, Catharine met a young clergyman named Fenn. He fell in love with her and asked her to marry him. But Catharine already liked someone else. This person was Reverend Patrick Cockburn. He was a scholar and a gentleman. They had been writing letters to each other, discussing philosophy and religion.

Reverend Cockburn told her he loved her, proposed, and she accepted. He became a priest in the Church of England in 1708. They got married. He then moved to Nayland, near Colchester, to start his new job. Catharine joined him later that year.

They lived there for some time. Then, Reverend Cockburn became a curate in London. They moved back to London until 1714. When King George I came to the throne, Reverend Cockburn had doubts about taking a special oath. He refused to take it, even though he prayed for the King. Because of this, he lost his church job and became poor.

For the next twelve years, he taught Latin to support his family. Catharine took on household duties. She learned needlework and other crafts. She also helped her husband and educated their children.

Writing again

Catharine didn't publish anything from her marriage in 1708 until 1724. In 1724, she wrote a letter to Dr. Holdsworth. She published it in 1727. Dr. Holdsworth replied, and Catharine wrote a strong answer. But publishers weren't interested. So, her "Vindication of Mr. Locke's Christian Principles" stayed as a manuscript. It was later published in her collected works.

One of her best poems was "A Poem, occasioned by the Busts set up in the Queen's Hermitage." She wrote about how Queen Caroline honored famous thinkers like Locke and Newton. Catharine was very good at explaining Locke's ideas. Locke himself approved of what she wrote about his views.

In 1726, Reverend Cockburn decided to take the oath he had refused earlier. In 1727, he was given a job at St. Paul's Chapel in Aberdeen. Catharine and her family moved there. She said goodbye to London, where she had experienced many successes and challenges.

Later, her husband was given a church job in Long Horseley, near Morpeth. But they stayed in Aberdeen until 1737. The church house in Long Horseley was far from the church. So, Catharine sometimes couldn't go to services if the weather was bad or she felt unwell.

In 1732, while in Aberdeen, she wrote "Verses occasioned by the Busts in the Queen's Hermitage." These were printed in Gentleman's Magazine in 1737. In 1743, her "Remarks upon some Writers in the Controversy concerning the Foundation of Moral Duty and Obligation" were published. These remarks were well-received. Her friend, Dr. Sharp, discussed these ideas with her in letters.

In 1744, Dr. Rutherford's "Essay on the Nature and Obligations of Virtue" came out. Catharine felt she needed to respond. In 1747, her "Remarks upon the Principles and Reasonings of Dr. Rutherford's Essay" were published. Bishop Warburton wrote the introduction. This work became very famous. Friends suggested collecting all her works. Catharine agreed to edit them herself. Many people supported this plan, but it wasn't fully completed.

Her writing style

Catharine's clear and strong ideas are shown in her poem "Calliope's Directions." In it, she explains the purpose of different types of poetry. She believed poetry should teach and inspire, not just entertain.

"Let none presume the hallowed way to tread

By other than the noblest motives led :

If for a sordid gain, or glittering fame,

To please without instructing be your aim,

To lower means your grovelling thoughts confine,

Unworthy of an art that's all divine."

Catharine stopped writing for about 16 to 18 years. People noticed when she started writing again. During those quiet years, she didn't read many new books. But she had her Bible and works by great writers like Shakespeare and Milton. Even though she was no longer in the busy city, her thoughts and reflections grew richer. Her mind stayed sharp because she used it constantly.

Her family life

Catharine and Reverend Cockburn had three daughters: Mary, Catherine, and Grissel. They also had one son, John. Catharine wrote a letter of advice to her son when he was a young man. It was full of wisdom and religious guidance. She told him that if he chose to be a minister, it should be to serve God.

In letters to her niece, Catharine often spoke happily about her "good son." In 1743, one of her daughters passed away. In January 1749, her husband also died. This was a huge shock, and Catharine's health failed. She died at Longhorsley on May 11, 1749. She was buried next to her husband and youngest daughter. Their tombstone had a sentence from the Bible: "Let their own works praise them in the gates."

Her lasting impact

Catharine Trotter was once very famous. But her reputation faded over the last 300 years. Recently, feminist critics like Anne Kelley have helped bring her work back into the spotlight. Some think her fame faded because she wrote most of her works when she was young. Also, people often focused on her youth and beauty instead of her writing.

Some historians believe her philosophical writings were emphasized too much. Her biographer, Thomas Birch, included only one play in his collection. He didn't even mention her novel Olinda's Adventures. Her philosophical works were sometimes seen as just copying others. This didn't help her reputation.

Today, many scholars study Catharine's plays for what they say about gender. Catharine herself knew the challenges women faced. She often wrote about these issues. Both her plays, where women are strong characters, and her personal life offer a lot for feminist studies.

Selected works

Plays she wrote

- Agnes de Castro, performed in London, December 1695 or 1696.

- Fatal Friendship, performed in London, 1698.

- Love at a Loss, or, Most Votes Carry It, performed in London, 1700.

- The Unhappy Penitent, performed in London, 1701.

- The Revolution of Sweden, performed in London, 1706.

Books she published

- Agnes de Castro, A Tragedy. (London: 1696).

- Fatal Friendship. A Tragedy. (London: 1698).

- Love at a Loss, or, Most Votes Carry It. A Comedy. (London: 1701).

- The Unhappy Penitent, A Tragedy. (London: 1701).

- A Defence of Mr. Lock's [sic.] Essay of Human Understanding. (London: 1702).

- The Revolution of Sweden. A Tragedy. (London: 1706).

- A Discourse concerning a Guide in Controversies, in Two Letters. (London: 1707).

- A Letter to Dr. Holdsworth, Occasioned by His Sermon Preached before the University of Oxford. (London: 1726).

- Remarks Upon the Principles and Reasonings of Dr. Rutherforth's Essay on the Nature and Obligations of Virtue. (London: 1747).

- The Works of Mrs. Catharine Cockburn, Theological, Moral, Dramatic, and Poetical. 2 vols. (London: 1751).

Other writings

- Olinda's Adventures; or, The Amours of a Young Lady, in Letters of Love and Gallantry and Several Other Subjects. (London: 1693).

- Epilogue, in Queen Catharine or, The Ruines[sic.] of Love, by Mary Pix. (London: 1698).

- "Calliope: The Heroick [sic.] Muse: On the Death of John Dryden, Esq.; By Mrs. C. T." in The Nine Muses. (London: 1700).

- "Poetical Essays; May 1737: Verses, occasion'd by the Busts in the Queen's Hermitage." Gentleman's Magazine, 7 (1737): 308.

Works you can find today

- Catharine Trotter Cockburn: Philosophical Writings. Ed. Patricia Sheridan. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006. ISBN: 1-55111-302-3.

- "Love at a Loss: or, Most Votes Carry It." Ed. Roxanne M. Kent-Drury. The Broadview Anthology of Restoration & Early Eighteenth-Century Drama. Ed. J. Douglas Canfield. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2003. 857–902. ISBN: 1-55111-581-6.

- Olinda's Adventures, Or, the Amours of a Young Lady. New York: AMS Press Inc., 2004. ISBN: 0-404-70138-8.

- Fatal Friendship. A Tragedy in Morgan, Fidelis. The Female Wits: Women Playwrights on the London Stage, 1660–1720. London, Virago, 1981.

- "Love at a Loss: or, Most Votes Carry It." in [Kendall] Love and Thunder: Plays by Women in the Age of Queen Anne. Methuen, 1988. ISBN: 1170114326.

- "Love at a Loss" and "The Revolution of Sweden", in ed. Derek Hughes, Eighteenth Century Women Playwrights, 6 vols, Pickering & Chatto: London, 2001, ISBN: 1851966161. Vol.2 Mary Pix and Catharine Trotter, ed. Anne Kelley.

- Catharine Trotter's The Adventures of a Young Lady and Other Works, ed. Anne Kelley. Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, 2006, ISBN: 0 7546 0967 7.

See also

In Spanish: Catharine Trotter para niños

In Spanish: Catharine Trotter para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |