William Warburton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend William Warburton |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Gloucester | |

|

|

| Diocese | Diocese of Gloucester |

| In Office | 1759–1779 |

| Predecessor | James Johnson |

| Successor | James Yorke |

| Other posts | Dean of Bristol (1757–1760) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 December 1698 Newark-on-Trent, England |

| Died | 7 June 1779 (aged 80) Gloucester, England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

William Warburton (born December 24, 1698 – died June 7, 1779) was an English writer and church leader. He became the Bishop of Gloucester in 1759 and held this important role until he passed away. He was also known for editing the works of his friends, the famous poet Alexander Pope and the playwright William Shakespeare.

Contents

Life of William Warburton

William Warburton was born in Newark, Nottinghamshire, England. His father, George Warburton, worked as the town clerk. William went to grammar schools in Oakham and Newark. In 1714, he started training to become a lawyer.

In 1719, after finishing his training, he began working as a lawyer in Newark. However, he had also studied Latin and Greek. He decided to change his career path and became a deacon in the church in 1723. He was ordained as a priest in 1726. Around this time, he also started meeting with important writers in London.

Early Church Roles

William Warburton received a small church position in Greasley, Nottinghamshire. The next year, he exchanged it for a position in Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire. He also served as the rector of Firsby from 1730 to 1756, though he never lived there. In 1728, he was given an honorary Master of Arts (M.A.) degree from the University of Cambridge.

For 18 years, Warburton spent much of his time studying at Brant Broughton. His first major book, Alliance between Church and State, was published in 1736. This book made him popular with the royal court. He might have received a higher position sooner, but Queen Caroline passed away.

Friendship with Alexander Pope

Warburton wrote several articles defending the writings of Alexander Pope. These articles helped him become good friends with the famous poet. This friendship greatly helped Warburton's career. Pope introduced him to important people like William Murray. Murray later helped Warburton become a preacher at Lincoln's Inn in 1746.

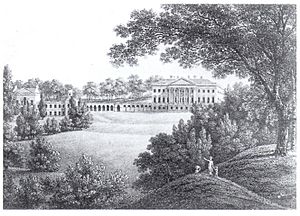

Pope also introduced Warburton to Ralph Allen. Allen was a wealthy man who, as writer Samuel Johnson said, "gave him his niece and his estate." In September 1745, Warburton married Allen's niece, Gertrude Tucker. From then on, he lived at Allen's large estate called Prior Park in Gloucestershire. Warburton eventually inherited Prior Park in 1764.

Becoming a Bishop

Warburton continued to rise in the church. He became a prebendary (a type of church official) of Gloucester in 1753. In 1754, he became a chaplain to the king. He was made a prebendary of Durham in 1755 and Dean of Bristol in 1757. Finally, in 1759, he achieved the important position of Bishop of Gloucester.

William Warburton's Writings

By 1727, Warburton had already written notes for Lewis Theobald's edition of Shakespeare. He also published a book called Critical and Philosophical Enquiry into the Causes of Miracles. He wrote anonymously for a pamphlet about the Court of Chancery, which was a legal court.

The Divine Legation

After his book on the Church and State, Warburton wrote his most famous work, Divine Legation of Moses demonstrated on the Principles of a Religious Deist. This book was published in two volumes between 1738 and 1741. In it, Warburton presented a very bold and clever idea about the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible).

Some people called deists argued that the Bible's early books didn't mention an afterlife. They used this to question if the books were truly from God. Warburton agreed that an afterlife wasn't directly taught in those books. But he argued that this actually proved they were divine. He said that no human lawgiver would forget to mention rewards or punishments in an afterlife to encourage good behavior.

Warburton's book showed his amazing power, knowledge, and original thinking. However, it also caused a lot of debate and made some people suspicious. He was criticized for being too kind to the ideas of Conyers Middleton, who was thought to have some unusual religious views. The book created many enemies for Warburton because he often described his critics as a "pestilent herd of libertine scribblers."

Defending Alexander Pope

Warburton also defended Alexander Pope's famous poem, Essay on Man. Some people thought the poem had ideas that went against religious beliefs. Warburton wrote articles in 1738–39 to defend it. It's not clear if Pope fully understood all the ideas in his own poem. But he was certainly happy to have Warburton defend him.

This led to a strong friendship between the two men. Pope saw Warburton as a helpful writer and editor. In 1743, Pope published a new edition of his poem Dunciad with Warburton as the editor. Pope even convinced Warburton to add a fourth book to the poem. When Pope died in 1744, he left half of his library and the rights to all his published works to Warburton. Warburton later published a complete collection of Pope's writings in 1751.

Editing Shakespeare

In 1747, Warburton published his own edition of Shakespeare's plays. This edition included some material from Pope's earlier work. He had previously shared his notes and changes for Shakespeare with Sir Thomas Hanmer. However, Hanmer used them without permission, which caused a big argument. Warburton also accused Lewis Theobald, another Shakespeare scholar, of stealing his ideas.

Later Writings and Debates

Warburton stayed busy by responding to attacks on his Divine Legation book. He also had a disagreement with Bolingbroke about Pope's actions. In 1750, he wrote a defense of the idea that the rebuilding of the temple of Jerusalem was miraculously stopped by Julian. This was in response to Conyers Middleton. People said Warburton's way of dealing with opponents was often rude, but it didn't harm his career.

He continued to write as long as his health allowed. He collected and published his sermons. He also tried to finish his Divine Legation, and more parts of it were published after his death. In 1754, he wrote a book defending revealed religion called View of Lord Bolingbroke's Philosophy. When David Hume wrote Natural History of Religion, Warburton responded with some Remarks in 1757. His friend Richard Hurd helped him with this.

In 1762, he strongly criticized Methodism in his book The Doctrine of Grace. He also had a sharp debate with Robert Lowth, who later became a bishop. This debate was about the book of Job. Lowth accused Warburton of not being scholarly enough and of being rude, which Warburton could not deny. His last important action was to start the Warburtonian lecture series in 1768. This lecture series aimed to prove the truth of revealed religion using prophecies from the Old and New Testaments.

Death and Legacy

William Warburton passed away in Gloucester on June 7, 1779. He did not have any children, as his only son had died before him. In 1781, his widow, Gertrude, married another clergyman, the Rev. Martin Stafford Smith.

Posthumous Publications

After his death, Warburton's works were edited and published in seven volumes in 1788 by Richard Hurd. Hurd also wrote a short biography. The letters between Warburton and Hurd were published in 1808 by Samuel Parr. These letters are important for understanding the literary history of that time. John Selby Watson wrote a biography of Warburton in 1863, and Mark Pattison wrote an essay about him in 1889.

See also

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- Shakespeare's editors

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |