Elizabeth Carter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Carter

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 16 December 1717 Deal, Kent, England |

| Died | 19 February 1806 (aged 88) Clarges Street, Piccadilly, City of Westminster, England |

| Pen name | Eliza |

| Occupation | Poet, classicist, writer, translator |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Literary movement | Bluestocking Circle |

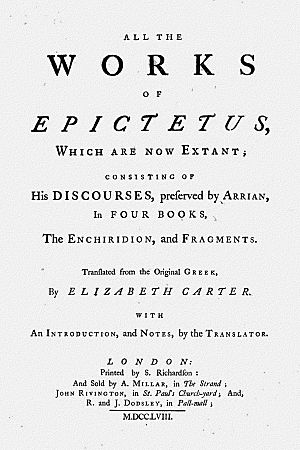

| Notable works | All the Works of Epictetus, Which are Now Extant |

Elizabeth Carter (who also used the pen name Eliza) was an amazing English writer, born on December 16, 1717, and passing away on February 19, 1806. She was a poet, a translator, and knew many languages, making her a true polymath (someone who knows a lot about many different subjects).

Elizabeth was part of a famous group called the Bluestocking Circle. This was a group of smart women who met to discuss literature and ideas. She became well-known for being the first person to translate the ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus's Discourses of Epictetus into English. She also wrote her own poems and translated works from French and Italian. Elizabeth had many famous friends, including Elizabeth Montagu, Hannah More, and Samuel Johnson, a very important writer of her time. She even helped edit some of Johnson's magazine, The Rambler.

Contents

Growing Up and Learning

Elizabeth Carter was born in Deal, Kent, England. She was the oldest child of Reverend Nicolas Carter, a church leader in Deal. Her mother, Margaret, passed away when Elizabeth was only ten years old. Her family home, made of red brick, can still be seen today near the seafront.

Elizabeth's father taught his many children Latin and Ancient Greek. At first, Elizabeth found her lessons very difficult. Her father almost gave up on teaching her, but Elizabeth was very determined. She worked incredibly hard to overcome her struggles. From a young age, she wanted to be both good and learned, and she worked towards this goal her whole life. She learned Greek and Latin so well that she understood the rules of the languages just by reading a lot of books. Her father also taught her Hebrew.

To help her learn French, her father sent her to live with a French family in Canterbury for a year. There, she learned to understand and speak French fluently. Later, she taught herself Italian, Spanish, German, and Portuguese. When she was much older, she even learned enough Arabic to read it without needing a dictionary!

Elizabeth studied many different subjects, including astronomy (the study of stars and planets) and ancient history. She learned to play musical instruments like the spinnet and the German flute. In her younger years, she enjoyed dancing. She could also draw quite well, knew how to manage a home, loved gardening, and spent her free time doing needlework (sewing and embroidery). To balance out her intense studies, she often took long walks and went to social gatherings.

Close Friends

Elizabeth Carter formed a very strong friendship with Elizabeth Montagu, who was born in 1720. They became close because they shared similar feelings and interests. Their friendship lasted throughout their long lives. Elizabeth Carter often visited Montagu at her country home and her house in London.

In 1741, Elizabeth Carter also became good friends with Catherine Talbot. They admired each other's talents, good qualities, and religious devotion. Through Catherine and her mother, Elizabeth met Thomas Secker, who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Writing Career

Elizabeth Carter started her writing career by writing poems. Her father was friends with Edward Cave, a publisher. When she was only 16, she published several poems in his magazine, The Gentleman's Magazine, using the pen name Eliza. When she visited London with her father, Cave introduced her to many important writers, including Dr. Samuel Johnson. In 1738, she published a collection of her poems. Although her father talked to her about marriage, she chose to remain single to stay independent. She adopted the title "Mrs." as was common for respected women of her time, even if they weren't married.

Elizabeth also translated two books into English: Examination of Mr Pope's "An Essay on Man" by Jean-Pierre de Crousaz and Newtonianism for Women by Francesco Algarotti.

In 1749, she began translating All the Works of Epictetus, Which are Now Extant. She sent her work to Archbishop Secker for him to check. She finished translating the Discourses in 1752 and later added the Enchiridion and other parts, along with her own introduction and notes. With help from her wealthy friends, the book was published in 1758. This translation was a huge success and made her famous. It was the first English translation of the Greek Stoic philosopher's works and earned her a lot of money. Her translation was so good that it went through three editions and remained a highly respected work. While preparing her book for printing, she also helped her youngest brother get ready for University of Cambridge.

Elizabeth Carter was good friends with Samuel Johnson and even helped edit some issues of his magazine, The Rambler, in the 1750s. Johnson once famously said about her, "My old friend Mrs. Carter could make a pudding as well as translate Epictetus from the Greek...." This showed that he admired both her intelligence and her practical skills.

Writing Style and Topics

Elizabeth Carter was known for her clear and sensible writing. Her poems were well-structured and showed a good flow of ideas.

Her letters, which were published after her death, were praised for their correct and clear language, good judgment, calm spirit, deep honesty, and strong religious faith. Her cheerful personality often shone through in her letters, sometimes with a playful and joyful tone.

Elizabeth was very interested in religious topics. She was influenced by her friend Hester Chapone and wrote in defense of the Christian faith, saying that the Bible had authority over human matters. Her strong belief in God can also be seen in her poems like "In Diem Natalem" and "Thoughts at Midnight."

In 1762, she published another collection of poems, with a poetic introduction written by George Lyttelton, 1st Baron Lyttelton.

In the late 1760s and early 1770s, Elizabeth lost several close friends, including Archbishop Secker and Catherine Talbot. In 1770, she edited and published some of Talbot's writings, including Reflections on the Seven Days of the Week and later Essays and Poems.

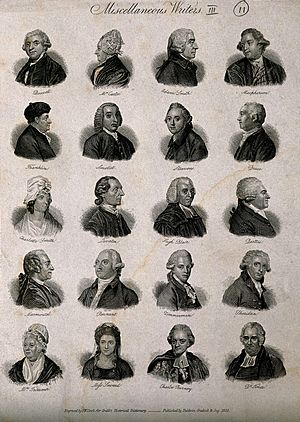

Nine Living Muses

Elizabeth Carter was included in a famous painting by Richard Samuel called The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain (1779). This painting showed nine important women writers of the time. However, the figures in the painting were so idealized that Elizabeth joked she couldn't recognize herself or anyone else!

Fanny Burney, another famous writer, described Elizabeth Carter in 1780 as "a really noble-looking woman." She added, "I never saw age so graceful in the female sex yet; her whole face seems to beam with goodness, piety, and philanthropy."

Life and Activities

In 1763, Elizabeth Carter went on a trip through Europe with the Earl of Bath and Edward and Elizabeth Montagu. They traveled through France, Belgium, and Germany, visiting places like Calais, Spa, Brussels, Ghent, Bruges, and Dunkirk. The trip lasted almost four months.

After the Earl of Bath died in 1764, his heir, Sir William Johnson Pulteney, generously gave Elizabeth Carter an annual payment of £100, which he soon increased to £150.

In 1762, Elizabeth bought a house in Deal. Her father rented part of it, and she managed the household. They had their own libraries and studied separately, but they ate meals together and spent evenings together for six months of the year. The other half of the year, Elizabeth usually stayed in London or visited friends in the countryside.

After her father passed away in 1774, Elizabeth received a small inheritance. In 1775, Edward Montagu died, and his wife Elizabeth inherited a large amount of money. One of the first things Mrs. Montagu did was to give Elizabeth Carter an annual payment of £100. Later, other friends also left her money. These gifts and inheritances gave her a secure income, meaning she didn't have to worry about money.

Elizabeth Carter was also a member of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, a group that worked to end slavery.

Later Years and Death

In 1796, Elizabeth Carter became very ill and never fully recovered. However, she continued to help the poor and support charities. In 1800, her loyal friend Mrs. Montagu died at the age of 80. The letters they wrote to each other between 1755 and 1799 were published after Elizabeth Carter's death.

Like many of her bluestocking friends, Elizabeth Carter lived a long life. As she got older, her hearing became worse, which made it harder for her to have conversations. On February 19, 1806, after a long period of declining health, Elizabeth Carter passed away in her home in Clarges Street, London.

Influence and Legacy

The famous novelist Samuel Richardson included Elizabeth Carter's poem "Ode to Wisdom" in his novel Clarissa (1747–1848). At first, he didn't say she wrote it, but it was later published correctly in Gentleman's Magazine, and Richardson apologized to her.

Elizabeth Gaskell, a novelist from the 1800s, mentioned Elizabeth Carter as a great example of letter writing in her novel Cranford. Virginia Woolf, another famous writer, saw Elizabeth Carter as an early feminist. She praised "the strong spirit of Eliza Carter – the brave old woman who tied a bell to her bed to wake up early and learn Greek."

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |