Samuel Richardson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Richardson

|

|

|---|---|

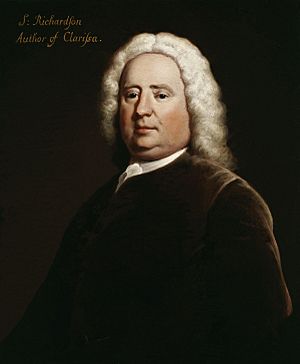

1750 portrait by Joseph Highmore

|

|

| Born | 19 August 1689 (baptised) Mackworth, Derbyshire, England |

| Died | 4 July 1761 (aged 71) Parsons Green, now in London, England |

| Occupation | Writer, printer and publisher |

| Language | English |

| Spouse | Martha Wilde, Elizabeth Leake |

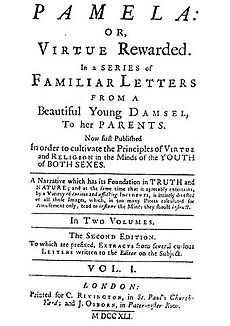

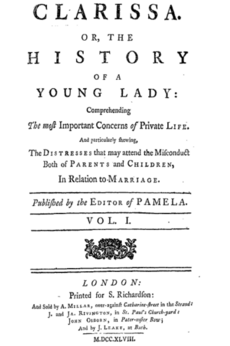

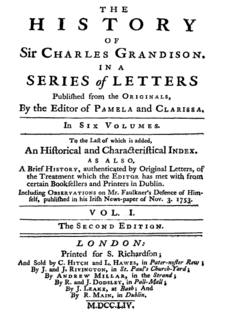

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer. He is famous for three novels written as a series of letters. These books are called Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748), and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753).

Richardson printed almost 500 different works, including newspapers and magazines. He often worked with a London bookseller named Andrew Millar. Richardson started as an apprentice to a printer. He later married his master's daughter. Sadly, he lost her and their six children. He remarried and had six more children. Four of his daughters lived to be adults, but he had no sons to take over his printing business.

He wrote his first novel when he was 51 years old. This made him one of the respected writers of his time. He knew famous people like Samuel Johnson and Sarah Fielding. He also printed books for the writer William Law. Richardson was a rival to Henry Fielding; they often wrote in ways that responded to each other's styles.

Contents

Samuel Richardson's Life Story

Samuel Richardson was one of nine children. He was probably born in 1689 in Mackworth, Derbyshire. His parents were Samuel and Elizabeth Richardson. We don't know the exact place he was born because Richardson kept it a secret. It seems his family was quite poor when he was a child.

His mother was from a good family, but her parents died young. They passed away during the Great Plague of London in 1665.

Richardson's father was a joiner, which is a type of carpenter. His father was good at drawing and understood building design. Some people thought he was a cabinetmaker who exported wood. His father's skills caught the attention of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth. However, this caused problems for the family. The Duke's rebellion failed in 1685, and he died. After this, Richardson's father had to leave his business in London. He moved his family to Derbyshire to live a simpler life.

Growing Up and Early Education

The Richardson family eventually returned to London. Young Samuel went to Christ's Hospital grammar school. However, his nephew said that Richardson never went to a better school than a "private grammar school" in Derbyshire.

Richardson didn't share much about his early life. But he did talk about how he became a writer. He loved telling stories to his friends. He also spent a lot of time writing letters.

I remember I was known early for being creative. I didn't like playing like other boys. My school friends called me Serious and Gravity. Five of them especially liked to ask me to tell them stories. Some stories I told were true, from my reading. Others I made up. They liked the made-up ones best and were often touched by them. One friend wanted me to write a history, like the story of Tommy Pots. I forget what it was about, but it was about a servant chosen by a fine young lady over a lord. All my stories, I can say, had a useful lesson.

When he was almost 11, Richardson wrote a letter to an older woman. She often criticized others. Richardson pretended to be an older person and warned her about her behavior. His handwriting showed it was his letter. The woman complained to his mother. His mother scolded him for being so bold with an older woman. But she also praised his good intentions.

After people knew he was good at writing, he started helping others. When he was 13, he helped girls write replies to love letters. He said he would help them "scold, and even refuse" someone. This was even when the girl's heart was "overflowing with esteem." This helped him practice his writing. But he later said these early experiences only helped him start to understand women. He truly understood them when he wrote Clarissa.

Starting a Career in Printing

Richardson's father wanted him to become a clergyman. But he couldn't afford the education needed. So, he let Samuel choose his own job. Samuel chose printing. He hoped it would let him read as much as he wanted.

At 17, in 1706, Richardson became an apprentice to a printer named John Wilde. Wilde's shop was in Golden Lion Court. Wilde was known for not liking his apprentices to have any free time.

I worked hard for seven years. My master didn't like me to have any free time that didn't make him money. Even the breaks my fellow workers forced him to give them, which other masters usually gave. I stole time from rest to read and improve my mind. I was writing letters to a rich gentleman who planned great things for me. These were my only chances to learn during my apprenticeship. I even bought my own candles so I wouldn't cost my master anything. He used to call me the pillar of his house. I made sure I wasn't too tired to do my duty to him during the day.

While working for Wilde, Richardson met a rich gentleman. This man was interested in Richardson's writing. They started writing letters to each other. When the gentleman died a few years later, Richardson lost a possible helper. This delayed his own writing career. He decided to focus on his apprenticeship. He worked his way up to a good position in the printing shop.

In 1713, Richardson finished his apprenticeship. He became an "Overseer and Corrector of a Printing-Office." This meant he ran his own shop. We don't know exactly where it was.

In 1719, Richardson was able to open his own printing shop. He moved near the Salisbury Court area, close to Fleet Street. His shop was actually on the corner of Blue Ball Court and Dorset Street. On November 23, 1721, Richardson married Martha Wilde. She was the daughter of his old boss. He brought her to live with him in the printing shop, which was also his home.

A big step in Richardson's career happened on August 6, 1722. He took on his first apprentices. Over their ten years of marriage, Samuel and Martha had five sons and one daughter. Three of their sons were named Samuel, but all three died young. Martha died on January 25, 1731. Their youngest son, Samuel, died a year later in 1732.

After his last son died, Richardson remarried. He married Elizabeth Leake, whose father was also a printer. They moved into another house on Blue Ball Court. Five of his apprentices also lived with them. Elizabeth and Richardson had six children (five daughters and one son). Four of their daughters – Mary, Martha, Anne, and Sarah – lived to be adults. Their son, another Samuel, was born in 1739 and died in 1740.

In 1733, Richardson got a big contract. With help from Arthur Onslow, he was hired by the House of Commons to print their Journals. The 26 volumes of this work greatly improved his business.

Later in 1733, he wrote a book called The Apprentice's Vade Mecum. It encouraged young men to be hardworking and disciplined. The book aimed to create "the perfect apprentice." It warned against popular entertainment like theaters, taverns, and gambling. Richardson believed apprentices could improve society. During this time, he took on more apprentices. He lost two apprentices, including his nephew, who he had hoped would take over his printing business.

Writing His First Novel

Richardson's printing business continued to do well. He printed the Daily Journal from 1736 to 1737. He also printed the Daily Gazetteer in 1738. By December 1738, his business was successful enough for him to rent a house in Fulham. This house was his home from 1739 to 1754.

In 1739, his friends Charles Rivington and John Osborn asked him to write a book of letters. It was meant to help people in the countryside who couldn't write well themselves. While writing this book, Richardson was inspired to write his first novel.

Richardson became a novelist on November 6, 1740, when he published Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded. Some people consider Pamela to be the "first novel in English" or the first modern novel. Richardson explained how he came up with the idea:

While working on [Rivington's and Osborn's collection], I wrote two or three letters to teach pretty girls who had to work as servants how to avoid dangers to their virtue. From this came Pamela... I never thought at first it would be one, much less two volumes... I thought the story, if written simply and naturally, might start a new kind of writing. It might turn young people away from fancy romance novels. It could get rid of unbelievable and amazing things that novels usually have. And it might help promote religion and good behavior.

Richardson started writing Pamela on November 10, 1739. His wife and her friends became so interested that he finished it by January 10, 1740. Pamela Andrews, the main character, showed Richardson's idea of proper female roles. Her love for housework was seen as a good example for women.

Pamela and its heroine were very popular. But they also led to many "anti-Pamelas." These included Henry Fielding's Shamela and Joseph Andrews, and Eliza Haywood's The Anti-Pamela. These books made fun of Pamela's perfect behavior.

Later that year, Richardson printed the book that inspired Pamela. It was called Letters written to and for particular Friends, on the most important Occasions. It taught people how to write letters and how to act wisely. The book had many stories and lessons. Richardson didn't think much of it, saying it was "not worthy of your perusal" and "intended for the lower classes of people."

Other writers created their own sequels to Pamela. These unofficial sequels were popular because readers wanted to know what happened next. This made Richardson write his own sequel, Pamela in her Exalted Condition, in December 1741. This sequel was not as well-received. It focused on Pamela's polite manners and married life. Readers' interest in the characters was fading. Richardson's focus on Pamela discussing morals and philosophy also made it less exciting.

Later Writing Career

After the Pamela sequels didn't do well, Richardson started a new novel. In 1744, he sent two chapters to Aaron Hill. Richardson asked Hill if he could help make the chapters shorter because the novel was very long. Hill refused, saying that Richardson's style was unique. He said that making it shorter would spoil the story.

In July, Richardson sent Hill a full plan of the story. He asked Hill to try again. Hill replied that it was "impossible" to question Richardson's success after Pamela. He was surprised Richardson had finished it already. However, Richardson wasn't happy with the novel until October 1746. Between 1744 and 1746, he tried to find readers to help him shorten the book. But his readers wanted to keep the whole thing.

Richardson also printed books for other authors. In 1742, he printed the third edition of Daniel Defoe's Tour through Great Britain. By 1748, Richardson was helping Sarah Fielding and her friend Jane Collier write novels. He was so impressed with Collier that he hired her as a governess for his daughters. In 1753, Collier wrote An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting with help from Sarah Fielding. Richardson printed this book. He also printed an edition of Edward Young's Night Thoughts in 1749.

By 1748, his novel Clarissa was fully published. Two volumes came out in November 1747, two in April 1748, and three in December 1748. Richardson's health was not good at this time. He had a simple diet of mostly vegetables and drank a lot of water. He suffered from "vague 'startings'" and tremors. He once wrote that writing helped him feel better than reading.

Despite his health, he continued to release the final volumes of Clarissa. He wrote to Hill that the whole story would be seven volumes. He later added more passages and letters to the fourth edition.

The public loved Clarissa. They called the main character "divine Clarissa." It was seen as Richardson's best work. It was quickly translated into French and German. People in England praised Richardson's "natural creativity." They liked how he put everyday life into his novel.

The last three volumes were delayed. Many readers wanted to know the ending. Some even demanded that Richardson write a happy ending. One person who wanted a happy ending was Henry Fielding. Fielding had previously mocked Richardson's Pamela. But he liked Clarissa and thought a happy ending would be fair. Others wanted the villain, Lovelace, to change and marry Clarissa. But Richardson refused to let a "reformed rake" be her husband. He would not change the ending.

Richardson wrote a pamphlet called Answer to the Letter of a Very Reverend and Worthy Gentleman. In it, he defended his characters. He explained that he tried hard not to make bad behavior seem good. This was unlike many other novels that used low-quality characters.

In 1749, Richardson's female friends asked him to create a good male character. They wanted him to show his idea of a good man and gentleman. He didn't agree at first, but he started working on the book in June 1750. Near the end of 1751, he sent a draft of The History of Sir Charles Grandison to a friend. The novel was finished in mid-1752.

When the novel was being printed in 1753, Richardson found out that Irish printers were trying to copy his work illegally. He immediately fired anyone he suspected of giving them early copies. He worked with many London printing companies to make sure his real edition came out first. The first four volumes were published on November 13, 1753. The next two followed in December. The last volume came out in March, completing a seven-volume series. A six-volume set was also published. Both were successful. In Grandison, Richardson made sure to show that bad characters should be avoided. He wanted to prove that the "rake" (a bad man) should not be admired.

Later Years and Death

In his final years, Richardson received visits from important people. These included Archbishop Secker and many London writers. By then, he was well-known and respected. He was also Master of the Stationers' Company, a group for printers and booksellers. In November 1754, Richardson and his family moved to a home in Parsons Green, which is now part of London. Around this time, Samuel Johnson wrote to Richardson asking for money to pay a debt. Richardson sent him more than enough money, and their friendship grew strong.

As he got older, Richardson's career as a novelist ended. Grandison was his last novel. He stopped writing fiction after that. Friends and admirers kept asking him to write more, suggesting new topics. But Richardson didn't like any of the ideas. He chose to spend his time writing letters to his friends. The only major work he wrote after Grandison was A Collection of the Moral and Instruction Sentiments, Maxims, Cautions, and Reflexions, contained in the Histories of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison. This book focused on moral lessons from his novels.

After June 1758, Richardson started having trouble sleeping. In June 1761, he had a paralytic stroke. His friend, Miss Talbot, described it on July 2, 1761:

Poor Mr. Richardson was struck on Sunday evening with a very bad paralytic stroke... It makes me happy that the last morning we spent together was especially friendly, quiet, and comfortable. It was May 28 – he looked so well then! One has long expected something like this. The illness came slowly, making his conversations less cheerful and lively. His hands, so good at guiding a pen, trembled more. And perhaps his temper became more irritable, which was not natural for such a kind and generous mind. You and I have recently regretted this, as it sometimes made his family less comfortable than his good principles and desire to spread happiness would have otherwise done.

Two days later, on July 4, 1761, Richardson died at Parsons Green. He was 71 years old. He was buried at St. Bride's Church in Fleet Street, near his first wife Martha.

During his life, Richardson's printing press produced about 10,000 items. These included novels, history books, laws from Parliament, and newspapers. His print shop was one of the busiest and most varied in the 18th century. He wanted his printing business to stay in his family. But his four sons and a nephew died. So, he left his press to another nephew. Richardson didn't trust this nephew's printing skills. His fears were right. After Richardson died, the press stopped producing good work and eventually closed down. Richardson owned the rights to most of his books. These were sold after his death.

What is an Epistolary Novel?

Richardson was a very skilled letter writer. He had this talent since he was a child. He wrote letters constantly throughout his life. Richardson believed that letters could show a person's character very well. He quickly started writing epistolary novels. This type of novel is told through letters, diary entries, or other documents. This form gave him the tools to create very different characters who spoke directly to the reader.

The epistolary style allowed readers to feel closer to the characters. This made them more involved in the story. Richardson's letter-based novels often showed different points of view. This let readers understand the story in various ways. Richardson hoped his readers would learn moral lessons from his books. He saw these novels as a way to improve people's lives.

In his first novel, Pamela, he explored the main character's life through her letters. The letters let the reader see Pamela grow and change. When Richardson wrote Clarissa, he was better at this style. He used letters from four different people. This created a complex story where characters influenced each other. However, the villain, Lovelace, also wrote letters, which led to tragedy. The letters in Clarissa showed how language could be used to communicate and explain.

By the time Richardson wrote Grandison, he changed how letters were used. They were no longer just for personal thoughts and feelings. Instead, they became a way for people to share their opinions on others' actions. They also celebrated good behavior. The letters were passed around for everyone to see. The characters in Pamela, Clarissa, and Grandison are shown in a very personal way. The first two use letters for "dramatic" purposes, while Grandison uses them for "celebratory" purposes.

Samuel Richardson's Books

Novels by Richardson

- Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740–1761) – This book was updated through 14 editions.

- Pamela in her Exalted Condition (1741–1761) – This is the sequel to Pamela. It was usually published with the first book in 4 volumes and updated through 12 editions.

- Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady (1747–61) – Updated through 4 editions.

- Letters and Passages Restored to Clarissa (1751)

- The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753–1761) – Corrected and updated through 4 editions.

- The History of Mrs. Beaumont – A Fragment – This book was never finished.

Other Writings and Supplements

- A Reply to the Criticism of Clarissa (1749)

- Meditations on Clarissa (1751)

- The Case of Samuel Richardson (1753)

- An Address to the Public (1754)

- 2 Letters Concerning Sir Charles Grandison (1754)

- A Collection of Moral Sentiments (1755)

- Conjectures on Original Composition in a Letter to the Author 1st and 2nd editions (1759) (with Edward Young)

Books Richardson Edited

- Aesop's Fables – 1st, 2nd, and 3rd editions (1739–1753)

- The Negotiations of Thomas Roe (1740)

- A Tour through Great Britain (4 Volumes) by Daniel Defoe – 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th editions (1742–1761)

- The Life of Sir William Harrington (knight) by Anna Meades – revised and corrected

Other Works by Richardson

- The Apprentice's Vade Mecum (1734)

- A Seasonable Examination of the Pleas and Pretensions Of the Proprietors of, and Subscribers to, Play-Houses, Erected in Defiance of the Royal License. With Observations on the Printed Case of the Players belonging to Drury-Lane and Covent-Garden Theatres (1735)

- Verses Addressed to Edward Cave and William Bowyer (1736)

- A compilation of letters published as a manual, with directions on How to think and act justly and prudently in the Common Concerns of Human Life (1741)

- The Familiar Letters 6 Editions (1741–1755)

- The Life and heroic Actions of Balbe Berton, Chevalier de Grillon (2 volumes) 1st and 2nd Editions by Lady Marguerite de Lussan (as assistant translator of an anonymous female translator)

- No. 97, The Rambler (1751)

Works Published After His Death

- 6 Letters upon Duelling (1765)

- Letter from an Uncle to his Nephew (1804)

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Richardson para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Richardson para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |