Three Sisters Bridge facts for kids

The Three Sisters Bridge was a bridge that was planned to go over the Potomac River in Washington, D.C.. It would have had supports, called piers, on the Three Sisters islets. People first thought about building a bridge here in the 1950s. The plan was officially suggested in the 1960s. However, many people protested, and the bridge project was stopped in the 1970s.

A bridge in this spot was first suggested way back in 1789. Since then, people have planned bridges here every few decades. In the 1950s, the George Washington Memorial Parkway was being built. People wanted to connect the parkway's sections on both sides of the Potomac River. They thought the Three Sisters Bridge could help link these parts.

The reasons for building the bridge changed over time. At one point, it was meant to be part of the "Inner Loop". This was a big system of highways planned for Washington, D.C. Later, it was supposed to bring the new Interstate 66 highway into the city.

The idea for the bridge caused a lot of arguments. It's a famous example of a "highway revolt". People living in the Georgetown neighborhood were against it. Many city groups, like the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, also opposed the bridge. People who didn't want big highways in D.C. also fought against it. They saw it as part of the unwanted Inner Loop.

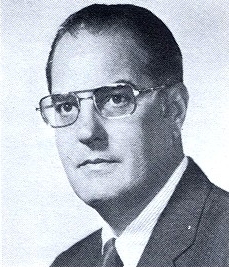

Some protests involved civil disobedience, where people broke rules peacefully. Others were more violent. The Three Sisters Bridge plan led to many lawsuits. One case even went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. A powerful politician named Representative William Natcher strongly supported the bridge. He was in charge of a key group in Congress. He stopped money for the Washington Metro subway system for six years. He hoped this would force the city to build the bridge.

But in late 1971, other members of the United States House of Representatives fought back. They released the Metro funds. With Natcher unable to force the city, the bridge plan basically ended. It was officially removed from federal plans in 1977.

Contents

Why Was the Bridge Proposed?

In the 1940s, Washington, D.C.'s population grew a lot. This caused terrible traffic jams. Many people believed the city needed better highways and a subway system. After World War II, planners also thought about moving government offices to the suburbs. This would make the government safer from attacks. New highways would be needed to bring workers into the city and help them move around quickly.

In 1946, a study suggested a system of highways for the D.C. area. It was like a wheel with spokes, centered around the White House. This plan was supported by important architects and city planners. In 1950, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) released a big plan for the area. This plan included the highways from the 1946 study.

In 1955, the D.C. government hired a company to suggest a new highway system. They proposed a large figure-eight shape within the city. This study was very important. It was included in a bigger plan made by different governments in the region. In 1957, Senator Clifford P. Case suggested a law to build a bridge at the Three Sisters. But Congress didn't act on it then.

In 1959, a study called the Mass Transportation Survey was released. This study proposed the Inner Loop highway system for D.C. It was mostly based on the 1946 report. As part of the Inner Loop, a new bridge at the Three Sisters was suggested. It would connect the Inner Loop in D.C. with a new highway in Virginia, which would later become Interstate 66.

In 1960, the D.C. Highway Department officially proposed the "Three Sisters Bridge." It was part of their plans for interstate highways. They wanted to extend the Whitehurst Freeway and connect it to the George Washington Memorial Parkway. A new highway, called Interstate 266, would go over the Three Sisters Bridge to Virginia. There, it would connect to Interstate 66.

Court Battles Over the Bridge

Public protests didn't do much at first. The mayor and city council couldn't really stop the bridge. Politicians like Natcher refused to give in.

However, the protests against the Three Sisters Bridge and Inner Loop led to many neighborhood groups forming. These groups started several legal challenges against the bridge. In 1969, one lawsuit said the bridge was planned without proper public input. But in January 1970, a judge ruled that a 1968 law allowed the bridge to skip these public steps.

Then, in February 1970, 10 environmental groups sued. They said the bridge broke federal environmental laws. In April, a court of appeals disagreed with the first judge. They said the government still had to hold a public hearing about the bridge's design. The court sent the case back to the first judge. They told him to stop construction. The judge didn't stop it right away. But on August 3, 1970, he ordered the city to hold the design hearing.

Meanwhile, other D.C. groups filed another lawsuit. They claimed the bridge's approval was due to political pressure, not good planning. This trial began in June. Many government papers showed the strong political pressure from politicians like Natcher. These papers also showed that city planners felt the bridge wasn't needed.

The Secretary of Transportation said political pressure didn't affect the decision. But a letter from President Nixon to Representative Natcher showed that stopping Metro funding was a big factor. The D.C. Highways director denied any pressure. The judge didn't stop the work right away. But on August 7, 1970, the judge ruled that political pressure was the main reason for the bridge's approval. He ordered work on the bridge to stop within 20 days. The city stopped work on August 27. By then, the bridge's foundations were finished, and the piers were almost at the water's surface. The city didn't appeal the judge's decision. The federal government did appeal, but the court of appeals agreed with the judge in October 1971.

The public hearing for the bridge design was set for December 1970. The design itself was questioned in May when a federal engineer worried about its single-span plan. When the hearing started on December 14, over 130 people spoke against the bridge. This led to a quick redesign by April 1971. The new plan used three spans to cross the Potomac River.

The Fight for Funding in Congress

As the court cases delayed the bridge, other things were happening. These events helped break Natcher's control over Metro funding. This was his main way of forcing the bridge to be built.

In 1968, surveys showed that people in Maryland and Virginia really wanted the Metro subway. They needed a fast way to get to their jobs in D.C. To start building the subway, the Metro agency asked voters in both states to approve money for it. Voters overwhelmingly said yes in November 1968. Natcher also agreed to release money for Metro's plans and land. Metro started construction in December 1969. But Natcher kept holding back money for building through 1971. People in Maryland and Virginia started to worry their money would be wasted. Soon, politicians from these states felt pressure to stop Natcher and get Metro built.

Opposition to highway building was also growing in Maryland and Virginia. In Virginia, people were starting to oppose building I-66. They saw the Three Sisters Bridge as a reason to build that highway. Representative Joel Broyhill suggested stopping all money for D.C. in 1971 if the city didn't build the bridge. But opponents pointed out that Broyhill owned land near the bridge. This land would become much more valuable if the bridge was built. Broyhill had a close election win in 1970. He was also accused of improper actions in 1971. Because of this, he turned against Natcher. He demanded that Metro funds be released.

In Maryland, people in Montgomery County also opposed new highways. State politicians from the area complained about congressmen from other states controlling their local issues. Representative Gilbert Gude and Senator Joseph Tydings called it "intolerable interference." In September 1971, a regional government group asked President Nixon to step in.

Growing Opposition in the House

Other members of Congress were also upset with Natcher. Representative Robert Giaimo was a senior member of the committee that handled D.C.'s money. By spring 1971, Giaimo was angry that Natcher was holding up the much-needed Metro. He believed Natcher was going against what the people of D.C. wanted.

On May 6, 1971, Giaimo tried to release Metro construction funds in a committee meeting. His idea was defeated. Giaimo, along with other representatives, wrote a report criticizing the committee. Giaimo promised to fight for the funds in the full House of Representatives. His attempt to add the funds was defeated, but the vote was much closer than expected.

The issue became very urgent. Metro's funding ran out on August 1, 1971. A law from 1970 required D.C. officials to report on the bridge's status by December 31, 1970. Broyhill visited President Nixon in November. He asked Nixon to make a public statement. Nixon did so the next day. He said the city was doing all it could given the legal issues. He also warned Congress that delays could kill the subway project and cost millions.

Metro also had an ally in the White House: presidential aide Egil "Bud" Krogh. Krogh liked living in D.C. and strongly supported Metro. He worked with Giaimo to build a group of politicians to oppose Natcher. This group included Republicans and Democrats, White House supporters, and the Congressional Black Caucus.

Success! Metro Funds Released

The big political battle happened on December 2, 1971. Nixon asked Republicans to support releasing the Metro money. He told them not to agree to any deals between Natcher and House Minority Leader Gerald Ford. Natcher had offered to release Metro funds if a court would rethink its earlier decision.

Nixon and his staff worked hard to convince Republican members to support Metro. Nixon even sent a personal letter to the Speaker of the House. Other politicians focused on getting younger members of the House to vote yes. Many friends and staff of Congress members also lobbied to get the motion passed.

There were seven hours of heated debate before the vote. The head of the full Appropriations Committee begged members not to "kick in the teeth of the Appropriations Committee." Another politician replied by asking if they wanted to kick in the teeth of the President. The Majority Leader and Majority Whip spoke in favor of releasing the money. Natcher strongly criticized the judge who had ruled against the bridge.

A first "test" vote failed. Then, a politician announced that the court had refused to rethink its decision. Giaimo then called for another vote. The pressure from the President and the court's announcement changed minds. The motion to release the funds passed 196 to 183. This was a big win, with 71 Republicans supporting it. The Washington Post called the vote "rare and stunning."

This vote immediately released $72 million for Metro construction. With other matching funds, another $212 million became available.

Supreme Court Decision and Final End

President Nixon directly ordered the Justice Department to ask the Supreme Court of the United States to hear its appeal on the Three Sisters Bridge case. This happened on January 17, 1972. However, the Supreme Court refused to hear the case on March 27, 1972. This meant the court of appeals' ruling against the bridge remained in place.

After this big vote in December 1971, Natcher never again threatened to stop Metro funding to force the bridge's construction.

Some bridge issues still remained, though. The building contracts for the bridge were not officially canceled until August 1972. One of the companies sued and was paid $350,000 in May 1975 for lost income.

Another attempt to make the city build the bridge happened in 1972, but it failed. The unfinished piers and foundations of the Three Sisters Bridge were washed away by Hurricane Agnes in June 1972. The House of Representatives tried to add a law to a 1972 highway bill. This law would have required building the bridge and the rest of the Inner Loop. But this idea was very controversial again. The bill failed because the House and Senate couldn't agree on including the bridge. The bridge provision was successfully included in the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1973.

But in January 1974, the D.C. City Council voted to put the Three Sisters Bridge, the Inner Loops, and all other planned highways aside. Congress didn't force the city to build the bridge. A big reason was that there was no interstate highway to connect it to. A study in February 1974 said the bridge was "inextricably linked" to building I-66. However, the study also admitted that I-66 could be built without the bridge. A day later, the U.S. Department of the Interior said the bridge would "severely impact" the beauty and history of the area.

The D.C. City Council held hearings in June 1975. They wanted to formally remove the bridge project from the Interstate Highway System. In May 1976, the council decided and asked if they could use the $493 million in federal bridge money for Metro construction instead. That summer, Virginia changed the route of I-66 because people in Arlington County opposed it. This new route made the Three Sisters Bridge unnecessary. Virginia Governor Mills E. Godwin, Jr. agreed to transfer Virginia's share of the bridge money ($30 million) to Metro construction if the route change was approved. The change was approved in July 1976. This left no money for the bridge.

In May 1977, the Department of Transportation allowed D.C. to remove the Three Sisters Bridge from its official transportation plan. The Washington Post said the bridge was "killed" yet again, adding, "This time it looks unusually permanent."

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |