Tone (linguistics) facts for kids

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without the correct software, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. |

Have you ever noticed how your voice goes up and down when you talk? This is called pitch. In some languages, changing the pitch of a word can completely change its meaning! This special use of pitch is called tone.

Imagine saying "ma" in different ways. In English, it might sound like a question ("ma?") or a statement ("ma."). But in a tonal language, each different pitch could mean a totally different word, like "mother," "horse," or "hemp"!

Languages that use tone to tell words apart are called tonal languages. The specific pitch patterns are sometimes called tonemes. You'll find many tonal languages in places like East and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific.

Tonal languages are different from languages with "pitch accent." In tonal languages, almost every part of a word (each syllable) can have its own tone. But in pitch-accent languages, only one syllable in a word might stand out with a special pitch.

Contents

How Tones Work

Most languages use pitch for things like showing emotion or emphasizing words. This is called intonation. But in tonal languages, the pitch is part of the word itself. This means you can have words that sound exactly the same (same consonants and vowels) but have different meanings just because their tones are different.

Two well-known tonal languages are Vietnamese and Chinese. They have very interesting tone systems that have been studied a lot.

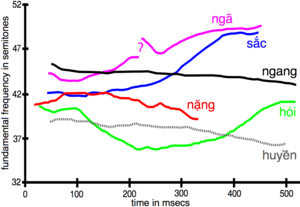

Vietnamese Tones

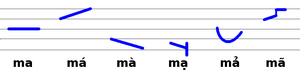

Vietnamese has six different tones. Each tone changes how a word sounds and what it means. Here's a look at them:

| Tone name | Description | Diacritic | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ngang ("flat") | Mid level pitch | ◌ | ma |

| huyền ("deep") | Low falling pitch | ◌̀ | mà |

| sắc ("sharp") | Mid rising pitch | ◌́ | má |

| nặng ("heavy") | Mid falling, short pitch | ़ | mạ |

| hỏi ("asking") | Mid falling-rising pitch | ◌̉ | mả |

| ngã ("tumbling") | Mid rising, with a slight break in the voice | ◌̃ | mã |

Chinese Tones

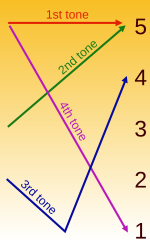

Mandarin Chinese has five tones. These tones are shown with special marks over the vowels in words.

- A high, flat tone (like saying "ah" with a high, steady voice).

- A tone that starts in the middle and rises up (like asking "huh?").

- A low tone that dips down a little (like saying "hmm" thoughtfully).

- A short, sharp falling tone, starting high and dropping quickly.

- A neutral tone, which doesn't have a specific pitch pattern. Its sound depends on the tone of the word before it.

These tones combine with a syllable like ma to make different words. For example, in pinyin (a way to write Chinese sounds):

- mā (媽/妈) means 'mother' (high tone).

- má (麻/麻) means 'hemp' (rising tone).

- mǎ (馬/马) means 'horse' (dipping tone).

- mà (罵/骂) means 'scold' (falling tone).

- ma (嗎/吗) is a question word (neutral tone).

You can combine these into a tongue-twister: Simplified: 妈妈骂马的麻吗?Traditional: 媽媽罵馬的麻嗎? Pinyin: Māma mà mǎde má ma? Translation: 'Is mom scolding the horse's hemp?'

Other Tongue Twisters

Here are some other fun tongue twisters from tonal languages:

- In Standard Thai:

ไหมใหม่ไหม้มั้ย. Translation: 'Does new silk burn?'

- A Vietnamese tongue twister:

Bấy nay bây bày bảy bẫy bậy. Translation: 'All along you've set up the seven traps incorrectly!'

- A Cantonese tongue twister:

一人因一日引一刃一印而忍 Translation: 'One person endures a day with one knife and one print.'

How Tones Change

Tones can interact with each other in interesting ways, a process called tone sandhi. This means a tone might change its sound depending on the tone of the word next to it.

Tone and Voice Quality

In some languages, like Vietnamese, tone is connected to how you use your voice. For example, some tones might be pronounced with a "creaky voice" (like a door creaking) or a "breathy voice" (like whispering). In Burmese, pitch and voice quality are so connected that they are part of one system.

Tone and Intonation

Lexical tones (the tones that change word meaning) and intonation (the pitch changes that show emotion or emphasis) both use changes in pitch. Think of it like this: lexical tones are small waves on the surface of the ocean, while intonation is the bigger swells underneath. The small waves (tones) ride on top of the big swells (intonation).

For example, in Thai, there are three main intonation patterns: falling (for finality), rising (for questions or unfinished thoughts), and "convoluted" (for showing conflict or emphasis). These patterns change how the five lexical tones of Thai sound.

Tone Polarity

In some languages, tones can be "default" or "marked." For example, in Navajo, most syllables have a low tone by default. But some syllables are "marked" with a high tone. In a related language called Sekani, it's the opposite: the default tone is high, and marked syllables have a low tone.

Types of Tones

Register Tones vs. Contour Tones

In many Bantu languages (spoken in Africa), tones are different based on their pitch level compared to other tones. So, a tone might be high, mid, or low. Sometimes, a single tone can cover a whole word, not just one syllable.

In Mandarin Chinese, tones are known for their unique contour or shape. This means they have a specific pattern of rising and falling pitch. For example, a tone might rise, fall, dip, or stay level. Each syllable in a Chinese word usually has its own tone.

Most tonal languages actually use a mix of both register and contour tones.

Word Tones vs. Syllable Tones

Another difference is whether tones apply to each individual syllable or to the whole word. In languages like Cantonese and Thai, each syllable can have its own tone. But in languages like Shanghainese or Swedish, the tone pattern applies to the entire word.

Tone sandhi is a situation where tones are on individual syllables but they affect each other. For example, in Mandarin Chinese, if two dipping tones are next to each other, the first one changes into a rising tone.

Lexical Tones vs. Grammatical Tones

- Lexical tones are used to tell words apart (like "mother" vs. "horse").

- Grammatical tones are used to change the grammar of a word. For example, they might change a verb from "go" to "gone," or show if a word is singular or plural.

For instance, in the Tlatepuzco Chinantec language (spoken in Mexico), tones can show if a verb is about something that happened, is happening, or might happen. They can also show who is doing the action (I, you, he/she, we).

In the Iau language, verbs don't have their own tone. Instead, a tone is added to the verb to show when the action happened or how it was completed.

Tones can even show if a word is the subject or object of a sentence, like in the Maasai language.

Number of Tones

Languages can have many different tones. Some languages might have up to five different pitch levels. Some languages, like the Kam language in China, have nine different tones! Some dialects of Chatino in Mexico might even have fourteen or more tones. The most complex tone systems are often found in Africa and the Americas.

Tonal Change

Tone Terracing

Tones are relative, meaning "high tone" is high compared to other tones in that moment, not an exact musical note. As you speak, your voice naturally tends to drop in pitch over time. This is called downdrift.

In some languages, a low tone can cause the next high or mid tone to drop a little bit, like steps on a staircase. This effect is called tone terracing. It means that a "high" tone at the end of a sentence might actually be lower in pitch than a "low" tone at the beginning!

Sometimes, a tone can even exist without a sound, like a "floating tone." This happens when a consonant or vowel disappears, but its tone remains and affects other tones.

Tone Sandhi

Tone sandhi is when a tone changes its shape because of a nearby tone. The affected tone might become a new sound that only appears in that situation, or it might change into another existing tone.

For example, in Mandarin Chinese, the words for "very" ([xɤn˨˩˦]) and "good" ([xaʊ˨˩˦]) both have a dipping tone. But when you put them together to say "very good," the first word's tone changes to a rising tone ([xɤn˧˥ xaʊ˨˩˦]).

Where Tones Are Used

In East Asia, tone is mostly used to tell words apart. This is common in languages like Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, and Hmong.

But in many African languages, tone can be used for both words and grammar. For example, in the Kru languages, nouns have complex tone systems, but verbs use simple tones that change to show things like past or present tense, or who is doing the action. Tone might be the only way to tell "you went" from "I won't go"!

In some West African languages like Yoruba, people can even communicate using "talking drums" or by whistling the tones of speech!

Tonal languages are not found everywhere. They are very common in certain language families like Niger-Congo, Sino-Tibetan, and Vietic.

Some scientists think that tonal languages might be more common in hot and humid climates because these conditions make them easier to pronounce. However, this idea is still being debated.

Tone and Grammar

Tone can also play a role in grammar, changing how words are used in sentences. For example, in Tlatepuzco Chinantec (a language in Mexico), tones can show if a verb is about something that happened, is happening, or might happen. They can also show if the action is done by "I," "we," "you," or "he/she."

In the Iau language, nouns have their own tones, but verbs don't. Instead, tones are added to verbs to show different aspects of the action, like if it's completed or still happening.

Tones can even help tell apart different grammatical cases, like the subject or object of a sentence, as seen in the Maasai language.

Some Chinese dialects use tone changes to show if a word is singular or plural, or if a verb is in the past tense.

How Tones Are Written

There are different ways to write down tones when describing a language.

- Numbers: One common way is to use numbers for pitch levels. For example, 1 might be low and 5 might be high. So, a rising tone might be written as "35" (starts mid, rises to high). This is often used for Chinese languages.

- Diacritics: Another way is to use special marks (diacritics) above or below letters, like the accents you see in French or Spanish. For example, an acute accent (á) might mean a high tone, and a grave accent (à) might mean a low tone. This is common in African languages and Vietnamese.

- Tone Letters: The Chao tone letters are like little pictures that show the shape of the tone (rising, falling, level). They are very clear and are often used for complex tone systems.

Tone in Different Regions

- Africa: In African languages, you often see acute (á) for high, macron (ā) for mid, and grave (à) for low tones. Sometimes, the mid tone isn't marked at all.

- Asia: In Chinese, numbers are often used (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4 for Mandarin tones). Vietnamese uses diacritics above or below vowels (e.g., à, á, ả, ã, ạ). The Hmong language uses letters at the end of words to show tone (e.g., b, m, d, j, v, s, g).

- North America: Many languages here, like Navajo, use tones. They might use acute accents for high tones and grave accents for low tones.

Sometimes, tones are not written at all, even in very tonal languages! For example, the Chinese navy has used toneless pinyin for messages for a long time.

How Tones Started

Scientists believe that many tonal languages weren't always tonal. Tones often developed from older sounds that disappeared. This process is called tonogenesis.

For example, in some languages, sounds like a "glottal stop" (a catch in your throat, like in "uh-oh") or a final "s" sound might have affected the pitch of the vowel before them. When these sounds disappeared, the pitch difference they created stayed behind and became a meaningful tone. This is how many tones in Chinese are thought to have started.

The same kinds of changes happened in many languages in East and Southeast Asia around the same time (between 1000 and 1500 AD), like in Thai and Vietnamese.

Sometimes, a language can even gain tones from neighboring languages through people speaking both languages. This is called contact-induced tonogenesis. For example, the Cherokee language in Oklahoma developed tones, but the Cherokee in North Carolina did not, even though they separated relatively recently.

List of Tonal Languages

Here are some places where you can find tonal languages:

- Africa: Most languages in Sub-Saharan Africa are tonal, like Igbo, Yoruba, and Zulu.

- Asia: Many languages in China and Southeast Asia are tonal, including most varieties of Chinese, Thai, Lao, and Vietnamese. The Hmong-Mien languages are known for having many tones.

- Americas: A large number of languages in North, South, and Central America are tonal. This includes many Athabaskan languages (like Navajo) and Oto-Manguean languages in Mexico.

- Europe: While most European languages are not tonal, some, like Swedish and Norwegian, have "pitch accent" features where the pitch of a stressed syllable can change a word's meaning. Some Indo-Aryan languages, like Punjabi, are also tonal.

Sometimes, it's hard to decide if a language is truly tonal. For example, the Ket language in Siberia has been described in different ways by different researchers. This shows that classifying a language as tonal can depend on how you define "tone."

See also

In Spanish: Tono (lingüística) para niños

In Spanish: Tono (lingüística) para niños

- Meeussen's rule

- Musical language

- Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |