Tui Manu'a Matelita facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Matelita |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Tui Manu'a | |

| Reign | 1891–1895 |

| Predecessor | Alalamua |

| Successor | Elisala |

| Born | 31 December 1872 |

| Died | 29 October 1895 (aged 22) |

| Burial | Tui Manu'a Graves Monument |

| Father | Arthur Paʻu Young |

| Mother | Amipelia |

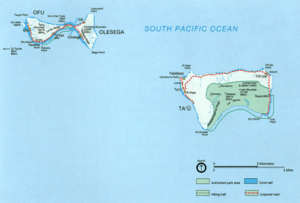

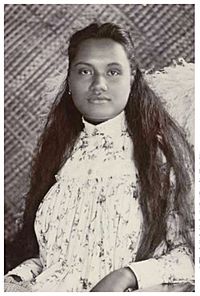

Tui Manu'a Matelita, also known as Margaret Young, Makelita, Matelika, or Lika, was a powerful leader in the Samoan Islands. She was born on December 31, 1872, and passed away on October 29, 1895. Matelita held the title of Tui Manu'a, which means she was the paramount chief or queen of the Manu'a islands. These islands are located in the eastern part of the Samoan Islands, which is now known as American Samoa.

During her time as Tui Manu'a from 1891 to 1895, Matelita mostly had a special ceremonial role. She lived in her home on Ta'ū island. A famous British writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, even visited her there. Matelita never married. This was because she didn't want to marry any of the local chiefs, and no other men were considered important enough to marry her. She died in 1895 and was buried at the Tui Manu'a Graves Monument.

Early Life

Matelita was born on December 31, 1872. Her parents were Arthur Paʻu Young and Amipelia. Her father had a mixed background, being half-Samoan and half-white. His father was a man named Young, who was either British or American, and his mother was a Samoan woman from Fasito'o.

Matelita's mother, Amipelia, came from a very important family. She was a descendant of earlier Tui Manu'a leaders, like Taliutafa Tupolo and Moaatoa. This meant Matelita was part of the anoalo class, which included direct descendants of the Tui Manu'a line.

Her family lived in the main villages of 'o Lumā and Sī'ufaga on Ta'ū island. This was the main island of the Manu'a group. Her father worked as a trader there. They lived in a two-story stone house located between the two villages, close to the Protestant Christian church.

Becoming Queen

After the previous Tui Manu'a, Alalamua, passed away, there was a disagreement about who should be the next leader. The faletolu, which was the council that usually chose the next Tui Manu'a, held an election.

There were two main candidates: Matelita and Taofi. Taofi was a son of an earlier Tui Manu'a named Tauveve. However, the anoalo group, led by Matelita's father, Arthur Paʻu Young, supported Matelita.

Even though some people from the main Tui Manu'a family didn't agree at first, Taofi eventually accepted the decision. So, Matelita became the new paramount chief of the Manu'a islands. She officially took the title on July 1, 1891.

Her crowning was a big traditional event. It included large feasts, special food offerings, and kava drinking. These celebrations took place in the days leading up to and after July 13, 1891.

Her Time as Queen

During her rule, Matelita mainly performed ceremonial duties. She lived on the main island of Ta'ū. In 1895, she gave an important speech to celebrate a new church.

Many European and American stories from her time, and even after, described her as mostly a symbolic leader. They sometimes called her a "white queen of the South Seas." As mentioned earlier, Matelita never married. She felt that none of the local chiefs were suitable, and no other men had the right status to marry her.

Meeting a Famous Writer

In 1894, Robert Louis Stevenson, a well-known British writer who lived in Samoa, visited Matelita and the Manu'a islands. He traveled on a ship called HMS Curacoa (1878).

Stevenson stayed on the island for two days. He was a guest in the queen's house and was served the traditional kava drink. He wrote about how Matelita seemed to have little to do. She also couldn't travel much outside of her main village of Ta'ū.

In a letter he wrote later, Stevenson shared his thoughts:

The three islands of Manu'a are independent, and are ruled over by a little slip of a half-caste girl about twenty, who sits all day in a pink gown, in a little white European house with about a quarter of an acre of roses in front of it, looking at the palm-trees on the village street, and listening to the surf. This, so far as I could discover, was all she had to do. "This is a very dull place," she said. It appears she could go to no other village for fear of raising the jealousy of her own people in the capital. And as for going about "tapatafaoing," as we say here, its cost was too enormous. A strong able-bodied native must walk in front of her and blow the conch shell continuously from the moment she leaves one house until the moment she enters another.

Death and Legacy

Matelita became ill in September 1895. She passed away peacefully in her sleep on October 29, 1895. Some later stories claimed she died in a fire caused by a kerosene lamp tipping over. However, reports from Protestant missionaries at the time said she died from her illness.

After Matelita's death, a son of her predecessor Alalamua, named Elisala, was chosen as the next Tui Manu'a in 1899. After Elisala died, the United States decided to end the Tui Manu'a title. The U.S. had already made the islands part of American Samoa. Matelita's brother, Chris Taliutafa Young, tried to claim the Tui Manu'a title in 1924, but he was not successful.

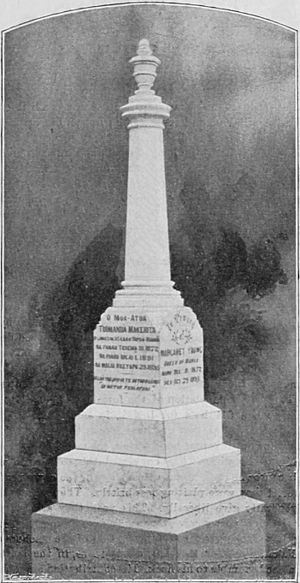

Matelita was buried next to some of the previous Tui Manu'a leaders. Later, her successor Elisala was also buried there. A special marble monument was built over her grave. This tombstone is about 6–7 ft (1.8–2.1 m) tall. It is the most noticeable monument in the royal burial ground, which is surrounded by a stone wall. The monument has a round column on a square base. Words are carved into the base in both English and Samoan language, remembering the life of the Tui Manu'a. It includes the words: "These are my last words to you all, 'May you live in peace'." This burial site is known as the Tui Manu'a Graves Monument. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2015.

An American anthropologist named Margaret Mead did research in Samoa between 1925 and 1926. Local people gave her the name Makelita in memory of the queen. During a local marriage ceremony, Mead even wore a dress that the late queen had woven.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |