UW Bothell Wetland Restoration Project facts for kids

The UW Bothell/Cascadia College Wetland Restoration Project is a 58-acre forest and wetland area. It's located where North Creek flows into a larger area in King County, Washington, USA. In 1994, the State of Washington bought this land. It was set aside for building the Bothell campus of the University of Washington and Cascadia College.

Building started in 1998, and so did the work to restore the creek and its surrounding wetland. Classes began for students in 2000. By 2001, the main part of the restoration was finished. Today, this site is still being restored and is used for learning about nature.

Contents

History of the Wetland

Before European settlers arrived, the land where the UW Bothell Wetlands now sit had small lakes and many natural water channels. How water moved through North Creek was affected by Lake Washington and water flowing from the surrounding land. In recent years, more buildings and roads have been built. This has made North Creek flow faster because water can't soak into the ground as easily.

How Water Changed Over Time

Before the restoration, North Creek was changed a lot. People straightened it, dug channels, and built walls (levees). These changes made it easier to float logs downstream to sawmills on Lake Washington. But these changes also stopped the creek from connecting to its natural flood areas. This led to poor water quality and fewer fish.

From 1913 to 1916, the Hiram Chittenden Locks were opened. This caused Lake Washington's water level to drop by 12 feet. This change dried out the natural floodplains. This allowed the land to be used for farming and building. Plants like reed canary grass, which used to feed farm animals, now grow wild. They compete with native plants that should be there.

The soil in North Creek's flood area has a mix of lake and marsh dirt, volcanic ash, and other natural deposits. The layers of soil show that the area used to have standing water and was a mix of marsh and forest wetland.

Past Plants and Animals

In the past, the floodplain had many shrubs and young plant communities. Large trees like Western Redcedar, Black Cottonwood, Douglas-fir, Big Leaf Maple, and Red Alder were common. These big trees were cut down before 1895. They were floated down North Creek to sawmills around Lake Washington.

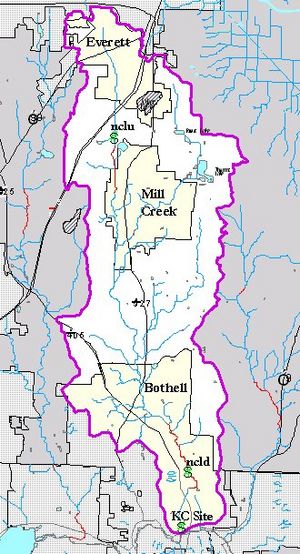

North Creek's Water Area

The North Creek watershed is a large area, about 30 square miles. All the water from this area eventually flows into the Sammamish River and then into Lake Washington. Most of the land in this watershed is developed with cities and towns. But there are still some forest areas, like the 64-acre North Creek Forest.

However, building and development greatly affect the water quality. This happens because areas along the creek are changed, forests are removed, and rainwater from hard surfaces isn't managed well. Also, polluted stormwater often runs off into the creek.

The Truly Family Farm

Since the 1930s, the area that is now the North Creek Wetland was used for farming and raising animals. Different owners, including the Truly Family, put in drainage systems. These systems changed how groundwater and surface water flowed on the property.

How the Wetland Was Designed to Be Restored

Building the UWB/Cascadia campus destroyed about 6 acres of a wetland on a hillside. Because of this, the State of Washington had to make up for the loss. This was required by the 1989 Federal Wetlands Delineation Protocol of the Clean Water Act. The State decided to restore the damaged floodplain to a very high standard. They restored nearly 10 times more wetland than was destroyed, right on the same site.

The restoration project aims to bring back important natural functions. These include cleaning water, protecting against floods, refilling groundwater, and keeping streamflow steady. The wetland was also designed to provide the right homes for fish, wildlife, and plants.

The restoration plan looked at the chemical, physical, and water processes found in healthy streams and wetlands. One important feature is micro-topography. These are small changes in ground height that create many different places for living things to thrive. Designers looked at other healthy wetlands in the Puget Sound Lowlands. They used these as examples to create the new stream channel shape. This design helps living things and chemicals interact between the land and water. For example, large pieces of wood were carefully placed in the creek. This created different types of homes along the stream banks. The success of the wetland restoration is largely thanks to these water and ground features.

The first step in restoring the floodplain was to remove the top 12 inches of soil from the southern part of the site. Then, up to 24 inches of new soil were added to the northern half. Creating this slope helped stop unwanted plants from growing.

The planting plan divided the wetland into 261 different environmental areas. Between 1998 and 2002, over 100,000 plants were put in the ground. Seven years after the first planting, the wetland project had met its goals for 10 years. The planting plan also thought about how plant communities change over time. The University of Washington Bothell expects the site to fully work as a natural ecosystem in another 20 to 30 years.

The restoration design used information about North Creek's water flow. It also used computer models of water movement and the natural potential of the site. The size of the new North Creek channel was planned by OTAK, using their water analysis. L.C. Lee & Associates, Inc. did the wetland's natural surveying and design.

Goals for the Restoration Design

The restoration project had seven main goals for the creek's design, and they were all met:

- Making the creek channel as long as possible.

- Allowing water to spend more time in contact with the wetlands.

- Creating extra channels for water during high flows.

- Placing large wood in the creek to guide its path and shape.

- Planning for increased water flows due to city growth in the North Creek area.

- Allowing the creek channel to move naturally within certain limits.

- Making sure people could see the wetland from both the campus and the highway.

The project also met all environmental rules. It restored the structure and function of two new channels in North Creek. This included reconnecting North Creek with its old floodplain. It also restored 58 acres of the wetland ecosystem.

Current Status of the Wetland

Current Plants and Animals

Today, the wetland has five different types of plant communities. These include evergreen forests, floodplain and riverside forests, floodplain scrub-shrub areas, marsh areas, and small wet spots.

Studies show that the number and variety of animal species are growing. Some common wetland animals seen today include the Beaver (Castor canadensis) and River Otter (Lutra canadensis). Different types of salmon like Chinook, Coho, and Sockeye have been seen. Trout and Bass species are also present.

The wetland is also home to many reptiles and amphibians. These include the Pacific treefrog (Pseudacris regilla), Red-legged frog (Rana aurora), Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), and the Northwestern garter snake (Thamnophis ordinoides).

Many bird species also live in the wetland. Common birds include the Great blue heron (Ardea Herodias), Canada goose (Branta Canadensis), Mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos), Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), Red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaincensis), and the American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos).

Taking Care of the Wetland

In the early years, taking care of the wetland involved removing unwanted plants. It also meant maintaining trails and thinning out overgrown bushes. Because new seeds of unwanted plants keep arriving, and beavers sometimes open up new areas, removing these plants is still needed.

To check if the wetland was meeting its goals, monitoring plans were created. These plans are required by the Clean Water Act. This monitoring also helps if unexpected things affect the wetland's function. Those events can be measured and dealt with.

The UW Bothell Wetland Restoration Project is in a city area. So, people need to manually plant certain species to help the ecosystem develop over time.

The wetland design included features like small changes in ground height and woody debris. These help make the site more diverse. UW Bothell is committed to keeping this natural diversity as conditions change. The University says that changes in North Creek's water flow will be managed only to protect buildings and other structures.

Learning at the Wetland

The Wetland Restoration Project at UW Bothell was one of the biggest wetland restorations in the area. This makes it a great place for researchers and teachers to learn. Over 30 classes from different programs at UW Bothell visit the campus wetlands.

Research projects have studied bats, crows, small stream animals, how beavers interact with plants, and more. Professional training, like learning about wetland restoration rules, is also taught here. This restoration is used as a very successful example. Ongoing research in the UW Bothell Wetland Restoration Project will provide a lot of information for future restoration efforts.

Research in the wetlands helps to keep track of how the restoration is growing. UW Bothell encourages students, staff, and other scientists to study the wetland. They just ask that the research has very little impact on the wetland's natural systems. Studies that involve just watching and observing are encouraged. Experiments are carefully reviewed, especially for any possible harm they might cause. Some research projects done in the wetland include:

- Studying the behavior of bats.

- Surveying land insects.

- Looking at small stream animals to check North Creek's health.

- Studying how beaver activity affects tree growth.

- Looking at how tent caterpillar outbreaks affect the restoration.

- Checking water quality in wet spots over time and how it links to North Creek's water quality.

Water Quality

The City of Bothell has been checking for Fecal Coliform Bacteria (FCB), including E. coli, in North Creek's smaller streams. In 2010, the City created a plan to control bacteria pollution. This plan included picking up pet waste to reduce FCB in surface waters. A later study found that the FCB in North Creek's smaller streams comes from many spread-out sources. FCB that comes from inside the wetland, like from waterfowl, is considered natural background levels. According to the Department of Ecology, this will not be part of the main water cleanup goals.

Challenges for the Wetland

North Creek is affected by pollution from specific points (like a pipe) and from many spread-out sources. When sewers overflow during heavy rain, it increases FCB and E. coli in North Creek. Special permits are given to deal with known pollution points. But spread-out sources, like poor land management and leaky septic systems, are harder to deal with. City stormwater likely contains FCB from pet waste too. The high levels of FCB in North Creek limit its use for fun activities. Also, low oxygen levels in the water negatively affect salmon when they try to lay eggs.