Ballard Locks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Chittenden Locks and Lake Washington Ship Canal

|

|

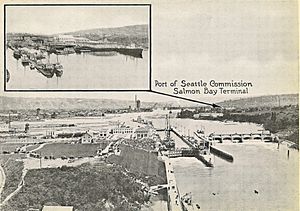

An aerial view of the locks, facing west

|

|

| Location | Salmon Bay, Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Built | 1911–1917 |

| Architect | Charles A. D. Young (locks and dam) Bebb and Gould (support buildings) |

| NRHP reference No. | 78002751 |

| Added to NRHP | December 14, 1978 |

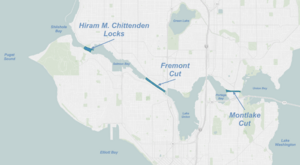

The Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, also known as the Ballard Locks, are a super important set of water locks in Seattle, Washington. They connect Salmon Bay to the Lake Washington Ship Canal. These locks are located between the neighborhoods of Ballard and Magnolia.

The Ballard Locks are super busy! More boats pass through them than any other lock in the United States. Plus, the locks, the special fish ladder, and the beautiful Carl S. English Jr. Botanical Gardens attract over a million visitors every year. This makes them one of Seattle's most popular places to visit. Building these locks completely changed Seattle's landscape. They lowered the water level of Lake Washington and Lake Union by about 8.8 feet. This created lots of new land along the waterfront. It also changed the direction of rivers and left old piers in Salmon Bay high and dry. The Locks are recognized as a historic site and a landmark of civil engineering.

Contents

Why the Locks Were Built

People started talking about building a waterway between Lake Washington and Puget Sound way back in 1854. They wanted to move logs, lumber, and fishing boats more easily. Later, in 1867, the United States Navy even supported the idea. They hoped to build a naval shipyard on Lake Washington.

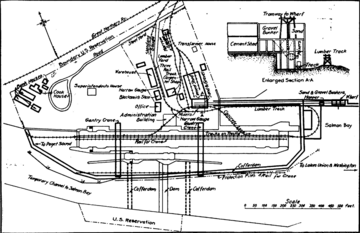

In 1891, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began planning the project. Some early work started in 1906, but the real construction began five years later. This was under the command of Hiram M. Chittenden. Because of these delays, the U.S. Navy built its shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, instead of Seattle.

Building the Locks: A Big Project

In early 1909, the state of Washington gave $250,000 to the Corps of Engineers. This money was for digging the canal between Lake Union and Lake Washington. In June 1910, the U.S. Congress approved the lock project. But they said local governments had to pay for the rest of the canals.

Construction faced some delays because of legal challenges. Mill owners in Ballard worried about losing their waterfront property in Salmon Bay. Also, some Lake Washington property owners were concerned.

Construction Begins and Lakes Change

Under Major James. B. Cavanaugh, who replaced Chittenden, work on the Ballard Locks began in 1911. There were no more legal problems. In July 1912, the lock gates closed for the first time. This turned Salmon Bay from saltwater into freshwater. The very first ship passed through the locks on August 3, 1916.

On August 25, 1916, a temporary dam at Montlake was opened. Over the next three months, Lake Washington drained. Its water level dropped by 8.8 feet. This also dried up over 1,000 acres of wetlands. The Black River dried up, and the Cedar River salmon run was cut off.

The Cedar River was rerouted into Lake Washington. This was done to make sure there was enough water to operate the Locks. The White River was also rerouted into the Puyallup River. Both the Cedar and White Rivers used to flow into the Duwamish River, causing frequent floods. Rerouting these rivers helped prevent floods and opened up new land for building. However, it greatly affected the Duwamish salmon runs. To help the salmon, new runs were introduced to migrate through the locks. The locks officially opened for boats on May 8, 1917. The project cost $3.5 million, with most of the money coming from the federal government.

New Bridges and Challenges

To make way for boats, three bridges along the ship canal were removed. New bridges were built, including the Ballard Bridge and Fremont Bridge in 1917. The University Bridge followed in 1919, and the Montlake Bridge in 1925. The Lake Washington Ship Canal project was officially finished in 1934.

Even though the project was a success, it had some issues. Saltwater started to move upstream towards Lake Union. This required special systems to keep it out. Also, the Cedar River was the main water source for both the lakes and Seattle's drinking water. Sometimes, there wasn't enough water to keep the lake level steady and operate the locks. On the other hand, with several rivers rerouted, flooding sometimes got worse in other areas. During big storms, the locks even had to be opened just to let water flow out.

How the Locks Work

The locks and their related facilities have three main jobs:

- They keep the water level of the freshwater Lake Washington and Lake Union steady. This level is about 20 to 22 feet above sea level.

- They stop saltwater from Puget Sound from mixing with the freshwater of the lakes. This is called "saltwater intrusion."

- They move boats between the different water levels of the lakes and Puget Sound.

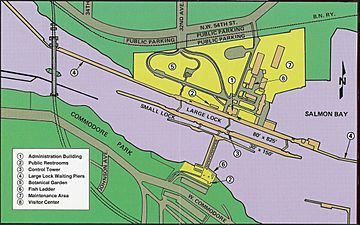

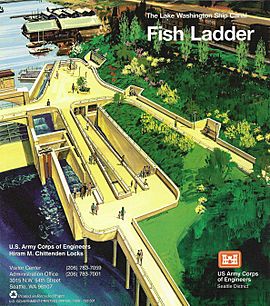

The complex has two locks: a small one (30 by 150 feet) and a large one (80 by 825 feet). There's also a 235-foot spillway with six gates to help control the water level. A special fish ladder is built into the locks. This helps anadromous fish, especially salmon, migrate.

The area also has a visitors center and the beautiful Carl S. English Jr. Botanical Gardens. The US Army Corps of Engineers operates the locks. They were named after US Army Major Hiram M. Chittenden. He was the Seattle District Engineer for the Corps of Engineers from 1906 to 1908. The locks were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

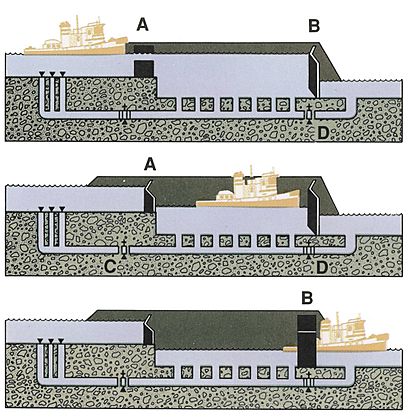

How Boats Pass Through

When boats want to go from the freshwater Lakes Washington and Union to Puget Sound, they enter the lock chamber through the open upper gates (marked A in the diagram). The lower gates (B) and the draining valve (D) are closed. Lock workers help the boat tie up and get ready.

Next, the upper gates (A) and the filling valve (C) close. The draining valve (D) opens, letting water drain out to Puget Sound by gravity.

When the water pressure is the same on both sides of the gate, the lower gates (B) open. This allows the boats to leave the lock chamber. The whole process is reversed when boats want to go from Puget Sound up to the lakes.

The Locks Themselves

The complex has two locks. Using the small lock when there aren't many boats saves freshwater during summer. This is important because the lakes get less water then. Having two locks also means one can be drained for repairs without stopping all boat traffic. The large lock is usually drained for about two weeks in November. The small lock is drained for a similar time, usually in March.

The locks can lift a large vessel (760 by 80 feet) about 26 feet. This takes only 10 to 15 minutes. They handle all kinds of boats, from kayaks to fishing boats coming back from the Bering Sea, and even cargo ships. More than 1 million tons of goods, fuel, building materials, and seafood pass through the locks every year.

The Spillway: Controlling Water Levels

South of the small lock is a spillway dam with gates. These gates help control the freshwater levels of the ship canal and lakes. They release or hold back water to keep the lake level within a 2-foot range, usually 20 to 22 feet above sea level. Keeping this level steady is important for floating bridges, boat docks, and for boats to pass under bridges.

Special "smolt flumes" in the spillway help young salmon safely travel downstream. Higher water levels are kept in the summer. This is good for recreation and helps the lakes store water in case of drought.

Keeping Saltwater Out

If too much saltwater got into Salmon Bay, it could harm the freshwater ecosystem. To stop this, a basin was dug just east of the large lock. Heavier saltwater settles into this basin and drains through a pipe. This pipe releases the saltwater downstream of the locks. In 1975, the saltwater drain was changed. Some saltwater from the basin was sent to the fish ladder to help attract fish.

To further block saltwater, a hinged barrier was installed in 1966. This hollow metal barrier is filled with air to stand upright, blocking the heavier saltwater. When very deep boats need to pass, the barrier is filled with water and sinks to the bottom.

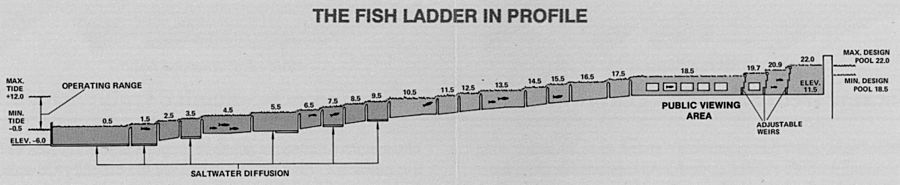

The Amazing Fish Ladder

The fish ladder at the Chittenden Locks is very special. It's unique because it's located where saltwater and freshwater meet. Usually, fish ladders are only in freshwater.

Pacific salmon are anadromous. This means they hatch in lakes, rivers, or fish hatcheries. Then they travel to the ocean. At the end of their lives, they return to freshwater to lay their eggs. Before the Locks were built, there weren't many salmon runs here. There was only a small stream connecting Lake Union to Salmon Bay. To get enough water for the Locks, the Cedar River was rerouted into Lake Washington. The Cedar and White Rivers used to flow into the Duwamish River, causing big floods for early settlers. Rerouting these rivers helped with floods but hurt the Duwamish salmon runs. To fix this, salmon runs were rerouted through the Locks. This included bringing in a major run of Sockeye Salmon from the Baker River.

The first fish ladder wasn't very good at attracting fish. Most salmon used the locks instead. This made them easy targets for predators. Many also got hurt by hitting the walls, gates, or boat propellers.

The Corps rebuilt the fish ladder in 1976. They increased the flow of "attraction water." This is freshwater flowing swiftly out of the ladder, which smells like the salmon's home. They also added more weirs, which are like steps. The old ladder had only 10 steps; the new one has 21. A special chamber mixes saltwater into the last 10 steps. As part of the rebuild, they added an underground room with windows where you can watch the fish!

Salmon smell the attraction water and recognize the scent of Lake Washington. They enter the ladder and either jump over each of the 21 steps or swim through tunnel-like openings. They exit the ladder into the freshwater of Salmon Bay. They keep following the waterway to the lake, river, or stream where they were born. There, the females lay eggs, and the males fertilize them. Most salmon die soon after laying eggs.

The young fish stay in freshwater until they are ready to go to the ocean as smolts. In a few years, the surviving adults return. They climb the fish ladder and reach their spawning ground to continue their life cycle. Out of millions of young fish, only a few survive to adulthood. Many things can cause them to die, like predators, fishing, diseases, low water levels, poor water quality, floods, and buildings along streams and lakes.

Visitors can watch the salmon through windows as they travel. The viewing area is open all year. But the best time to see salmon is during spawning season, from early July through mid-August. There's also public art that shares poems about the salmon's journey.

Types of Fish You Might See

Several types of salmon and trout regularly use the fish ladder at the Chittenden Locks:

- Chinook (king) salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

- Coho (silver) salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

- Sockeye (red) salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka)

Sockeye salmon mostly go up the Cedar River to lay eggs, often ending up at the Landsberg Dam Hatchery. Chinook and Coho salmon usually go up Issaquah Creek, many reaching the Issaquah Hatchery.

Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) used to migrate through the Locks. However, none have been seen in years, and their run is now considered gone.

- Corps of Engineers Foundation http://www.ballardlocks.org

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |