Ulster Workers' Council strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ulster Workers' Council strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Troubles | |||

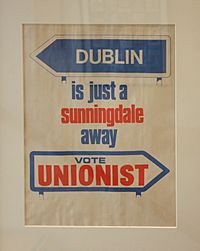

A 1974 poster by unionists opposed to the Sunningdale Agreement. It implied that the agreement would lead to "Dublin Rule" (that is, a united Ireland), to which unionists were opposed.

|

|||

| Date | 15–28 May 1974 | ||

| Location |

Throughout Northern Ireland

|

||

| Goals | Abolition of the Sunningdale Agreement and Government of Northern Ireland | ||

| Methods |

|

||

| Resulted in | Government of Northern Ireland prorogued; direct rule re-introduced | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a major event during "the Troubles" in Northern Ireland. It was a general strike, meaning many workers stopped working at the same time. This strike happened from May 15 to May 28, 1974.

The strike was called by unionists. These were people who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom. They were against the Sunningdale Agreement, a new political plan. This agreement, signed in December 1973, aimed to share power in Northern Ireland. It would have given Irish nationalists (people who wanted a united Ireland) a role in government. It also suggested a link with the Republic of Ireland's government. Unionists strongly opposed these ideas.

The Ulster Workers' Council and the Ulster Army Council organized the strike. These groups included Ulster loyalist paramilitary groups. Paramilitaries are groups that act like armies but are not official. Examples included the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)]. These groups helped the strike by blocking roads. They also used intimidation to make sure people did not go to work. During the two-week strike, 39 civilians were killed.

The strike was successful in its goal. It caused the power-sharing government in Northern Ireland to collapse. This government was called the Northern Ireland Executive. After the strike, the British Parliament in Westminster took back control. This was known as 'Direct Rule'.

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Merlyn Rees, later described the strike. He called it an "outbreak of Ulster nationalism". This meant it showed a strong desire for Northern Ireland to be separate.

Contents

Key Moments of the Strike

Starting the Strike: May 14-15

On May 14, 1974, there was a big debate. It happened in the Northern Ireland Assembly. The debate was about power-sharing and the Council of Ireland. This Council was part of the Sunningdale Agreement. It was meant to help Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and the UK work together. The plan was voted down.

After the vote, a leader of the UWC, Harry Murray, announced a general strike. It would start the next day. The UWC had planned this date for a while. They expected the vote to fail.

The strike began slowly on May 15. Many workers still went to their jobs. But by lunchtime, more workers started to leave. The port of Larne was soon blocked. UDA and UVF members made sure no ships could enter or leave. Roadblocks were set up across Northern Ireland. These were often made from hijacked vehicles. Electricity was also cut off. Workers at the Ballylumford power station joined the strike. The UWC said they would keep essential services running.

Strike Spreads: May 16-17

By May 16, the strike affected farming. Milk and fresh food could not be moved. The UWC then listed essential services that could continue. These included bakeries, hospitals, and banks. They even ordered pubs to close. This was partly because striking workers' wives complained about heavy drinking.

In Belfast, loyalist paramilitaries forced factories to close. They used petrol bombs to scare workers away. Even in Catholic towns, work stopped due to power cuts.

On May 17, the UVF set off four car bombs in the Republic of Ireland. These attacks killed 33 civilians. Almost 300 people were hurt. This was the deadliest day of "the Troubles." No warnings were given. A UDA and UWC spokesperson, Sammy Smyth, said he was "very happy" about the bombings. Postal services in Northern Ireland also stopped due to intimidation.

Escalation and Support: May 18-20

On May 18, the UWC said they wanted to make the strike even bigger. They called for a complete stoppage. Some people were still unsure if the strike would succeed. But the British Army warned they could not run power stations alone.

On May 19, Merlyn Rees declared a State of Emergency. He then met with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Meanwhile, the United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC) publicly supported the UWC. The UUUC was a group of pro-strike political parties.

With the UUUC's support, the UWC set up a committee on May 20. This committee, led by Glenn Barr, helped run the strike. It included political leaders and paramilitary heads. Electricity levels dropped very low. The British government sent 500 more troops to Northern Ireland.

Government Response and Impact: May 21-24

On May 21, the General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), Len Murray, led a 'back-to-work' march. Only 200 people joined. Loyalists attacked some marchers. Prime Minister Harold Wilson spoke at Westminster. He called the strike "sectarian."

On May 22, the government tried to end the strike. They offered to delay parts of the Sunningdale Agreement. They also offered to reduce the size of the Council of Ireland. But the UWC leaders rejected these offers. Loyalists bombed a railway line. They also bombed a shop that stayed open.

On May 23, security forces removed some loyalist roadblocks. But they were quickly put back up. The strike also affected school exams. Political leaders discussed sending the army to power stations. But the Prime Minister refused.

On May 24, Harold Wilson and Northern Ireland leaders met. They said they would not negotiate with groups outside normal politics. Loyalists shot and killed two Catholic civilians near Ballymena. They had attacked other pubs for staying open. A petrol station was also bombed. Two teenagers died when their car crashed into a loyalist roadblock near Dungannon.

Strike's End: May 25-28

On May 25, Harold Wilson gave a TV speech. He called the strikers "spongers." Many Northern Irish Protestants saw this as an insult to them all. This made more people support the strike. People even started wearing small sponges as a sign of support. A Catholic civilian was found beaten to death in Belfast.

On May 26, the British Army raided loyalist areas. They arrested over thirty suspected activists. The UWC said their permit system was working. They claimed it ensured essential services like petrol.

On May 27, the army took over twenty petrol stations. They would supply petrol to essential drivers with permits. In response, the UWC stopped overseeing essential services. They said the army could now handle everything. They also announced that the Ballylumford power station would close. Gas supplies in Belfast also dropped.

On May 28, Brian Faulkner, the Chief Executive, resigned. He was the head of the power-sharing government. His supporters also resigned. This effectively ended the Northern Ireland Executive. Faulkner said he hoped Catholics and Protestants could still work together. Farmers in tractors blocked the entrance to the Stormont parliament. News of the government's collapse spread. This led to celebrations in Protestant areas.

Aftermath of the Strike

Most people returned to work on May 29. The UWC formally ended the strike that day. The Northern Ireland Assembly was officially closed down later.

The strike showed a big difference between political leaders and worker leaders. Ian Paisley, a political leader, claimed a personal victory. But Harry Murray, a key UWC organizer, went back to his shipyard job. The political leaders soon stopped working with Andy Tyrie, a paramilitary leader.

Merlyn Rees saw the strike as a sign of Ulster nationalism. This was the idea that Northern Ireland should be its own nation. Journalist Robert Fisk agreed. He wrote that for fifteen days, Northern Ireland became "totally ungovernable." He said a "self-elected provisional government" took over. They controlled food, water, electricity, and transport.

Another writer, T. E. Utley, also noted that the UWC acted like a shadow government. He praised the strike's organization. He said it was done with "discipline and efficiency." The strikers even set up their own petrol rationing and issued passes. They also collected and gave out food.

For a while, the UDA paramilitary group explored the idea of Ulster nationalism. They even created a plan for an independent Northern Ireland in 1979. But this idea did not gain much support. The UVF also tried to form a political party, but it also struggled.

Harold Wilson, the British Prime Minister, learned from the strike. He realized that the British government could not force a solution on Northern Ireland. So, the next attempt at a local government was different. It was called the Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention in 1975. This body was elected, and politicians were supposed to decide the future. However, it failed to reach any agreements.

The UWC tried to organize a second strike in 1977. But this time, it did not have wide support. It failed and caused problems between the Democratic Unionist Party and the UDA.

Images for kids

See also

- Ulster Says No

- Timeline of Ulster Defence Association actions

- Timeline of Ulster Volunteer Force actions

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |