Valerius Maximus facts for kids

Valerius Maximus was a Roman writer who lived in the 1st century AD. He wrote a collection of historical stories called Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings. This book is also known as Facta et dicta memorabilia. He worked during the rule of Emperor Tiberius, from 14 AD to 37 AD.

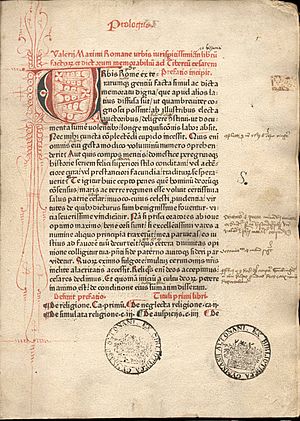

During the Middle Ages, Valerius Maximus was one of the most copied Latin writers. Only Priscian, a grammarian, had more copies of his work. Because of this, more than 600 old handwritten copies (manuscripts) of his books still exist today.

About Valerius Maximus

We don't know much about Valerius Maximus's life. His family was not wealthy or well-known. He owed a lot to Sextus Pompeius, who was a powerful Roman official. Valerius traveled with Pompeius to the East in 27 AD. Pompeius was part of a group of writers, and the famous poet Ovid was in it too. Pompeius was also a close friend of Germanicus, a prince in the Roman imperial family.

Some people have said that Valerius Maximus praised Emperor Tiberius too much. However, others argue that his writings were not overly flattering. They say his descriptions of the emperor were common for writers of his time. He also wrote strongly against Sejanus, another powerful figure.

His Writing Style

Valerius Maximus's writing style suggests he was a professional speaker or teacher of public speaking. His book was meant to be a collection of historical stories. Students could use these stories to make their speeches more interesting. The full title of his work is Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings.

The stories in his book are not arranged in a strict order. Each book is divided into sections. Each section has a title, usually about a good quality or a bad one. The stories in that section then show examples of that quality.

Most of the stories are about Roman history. But each section also has extra stories from other cultures, mostly the Greeks. Valerius often showed two main ideas in his writing. First, he felt that Romans of his time were not as good as their ancestors from the Roman Republic. Second, he believed that Romans were still better than other people in the world, especially the Greeks.

Valerius got most of his information from writers like Cicero, Livy, Sallust, and Pompeius Trogus. He was not always perfectly accurate with his facts. But his stories were good examples for what he wanted to show. He also used some sources that are now lost. His work gives us a few clues about the time of Emperor Tiberius. It also shares some details about ancient Roman religion and art.

His Legacy

Valerius Maximus's collection was very popular in schools. Its popularity in the Middle Ages is clear because so many copies of it still exist. Some even said it was the most important book after the Bible. Like other schoolbooks, shorter versions (called epitomes) were made. One complete short version, probably from the 4th or 5th century, was made by Julius Paris.

During the Renaissance, his full book became a key part of Latin studies. This is when his influence was probably strongest. For example, the famous writer Dante used Valerius's book for details in his own stories.

There is a tenth book sometimes found with Valerius's works. It is called Liber de Praenominibus. But this book was written by someone else much later.

Editions and Translations

Many versions of Valerius Maximus's work have been published over time. Modern editions include those by R. Combès (with a French translation), J. Briscoe, and D.R. Shackleton Baily (with an English translation).

In 1614, a Dutch translation was published. Famous artists like Rembrandt read this translation. It even inspired new subjects for paintings, such as Artemisia drinking her husband's ashes.

More than 600 handwritten copies (manuscripts) of Valerius's work have survived. If you count the shorter versions, there are over 800. This is more than any other Latin prose writer except Priscian. Most of these copies are from the late Middle Ages. However, about 30 copies are older than the 12th century. The three oldest manuscripts are very important for studying his original text:

- The Burgerbibliothek in Bern, Switzerland, manuscript n°366 (called manuscript A).

- The Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy, Ashburnham 1899 (called manuscript L). Both A and L were written in northern France in the 9th century. They came from a shared older copy.

- The Royal Library in Brussels, Belgium, manuscript n°5336 (called manuscript G). This copy was likely made at the Gembloux Abbey in the 11th century. Manuscript G seems to have come from a different older copy than A and L.

See also

In Spanish: Valerio Máximo para niños

In Spanish: Valerio Máximo para niños