Viral life cycle facts for kids

|

A virus is a tiny, tiny germ that can only make copies of itself inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses are super small, way smaller than even the smallest bacteria. You can't see them with a regular microscope! You need a special, powerful electron microscope to get a good look.

Viruses can infect all life forms, like animals, plants, and even tiny microorganisms such as bacteria. You can find viruses almost everywhere on Earth. They are the most common type of living thing!

How Small Are Viruses?

To measure viruses, scientists use a unit called a nanometer (nm). A nanometer is incredibly small. It's one billionth of a meter! Imagine lining up one billion tiny LEGO bricks. They would stretch out to be one meter long! That's how small a nanometer is.

Think about this: a single grain of sand is about 100,000 nanometers wide. A human hair is about 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers wide. Viruses are much, much smaller than that! They usually range from about 20 nanometers to 400 nanometers in size.

What Are Viruses Made Of?

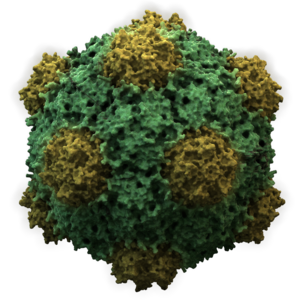

Unlike living things like plants and animals, viruses are not made of cells. They are much simpler. A virus is basically a tiny package of genetic material. This material is either DNA or RNA. Think of it like a secret code!

This genetic material is wrapped up in a protein coat. This coat protects the genetic material. It also helps the virus attach to cells. Some viruses even have an extra layer called a membrane. This is like an extra layer of protection. Imagine a tiny, hard candy shell with a special message inside. That's a bit like what a virus is!

How Do Viruses Work? (The Viral Life Cycle)

Viruses can only make copies of themselves inside the cells of a living organism. This could be a plant, an animal, or even a bacterium. They cannot reproduce on their own. They need to "take over" a cell's machinery to do the job for them.

Here is how a virus usually works:

1. Attachment: Sticking to a Cell

The virus first attaches itself to a cell. Think of it like a key fitting into a lock. Each virus has a specific "key." This key only fits certain types of "locks," which are the cells. This is why some viruses only infect certain plants or animals.

2. Entry: Getting Inside

Once attached, the virus enters the cell. It might inject its genetic material into the cell. Or, the cell might "swallow" the whole virus.

3. Replication: Making Copies

Inside the cell, the virus uses the cell's machinery. It makes many copies of its genetic material. It also makes copies of its protein coat. It's like the virus takes over a factory. It then uses the factory to produce more of itself!

4. Assembly: Building New Viruses

The newly made genetic material and protein coats then come together. They assemble into brand new viruses.

5. Shedding: Leaving the Cell

The new viruses then burst out of the cell. They are now ready to infect more cells. This process is called shedding. It is the final stage in the viral life cycle. Sometimes the cell is destroyed when the viruses leave. Other times, the cell survives but becomes weaker.

6. Latency: Hiding Out

Some viruses can "hide" inside a cell. This means they might avoid the cell's defenses. They can also avoid the immune system. This can help the virus survive for a long time. This hiding is called latency. During this time, the virus does not make new copies. It stays inactive. It waits until something, like light or stress, makes it active again.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |