Walla Walla Council (1855) facts for kids

The Walla Walla Council of 1855 was a very important meeting held in 1855 in the Pacific Northwest. It brought together leaders from the United States government and several independent Native American tribal nations, including the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama. During this council, several treaties were signed where the tribal nations agreed to share vast amounts of their traditional lands with the United States in exchange for promises of money, goods, and designated areas called "reservations" where they could continue their way of life. These treaties, however, were later broken by the U.S. government, leading to difficult times and conflicts.

Contents

- Introduction: A Grand Meeting in the Valley

- When and Where Did It Happen?

- Who Were the Main People Involved?

- Governor Isaac I. Stevens: The U.S. Representative

- The Treaties of 1855: Promises and Land

- Ratification: Making it Official

- Why Were These Treaties So Important?

- Broken Promises: A Sad Chapter

- What Happened Next? A Time of Conflict

- Legacy of the Walla Walla Council

Introduction: A Grand Meeting in the Valley

Imagine a time long, long ago, back in 1855. In a beautiful, wide-open valley in what we now call the Pacific Northwest, a very important gathering took place. This wasn't just any meeting; it was a grand council, a big discussion, between different groups of people who had very different ideas about the land. On one side were representatives from the United States government, and on the other were the respected leaders of several powerful and independent Native American tribal nations: the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama. This historic event is known as the Walla Walla Council of 1855.

The main goal of this council was to make agreements, called treaties, about land. The United States was growing rapidly, and more settlers were moving west, looking for new places to live and farm. The government wanted to acquire large areas of land for these new settlers. However, the tribal nations had lived on and cared for these lands for thousands of years, and these lands were central to their cultures, their spiritual beliefs, and their very survival. The council was an attempt to find a way for everyone to live together, but it involved some very big decisions and promises that would shape the future of the entire region.

When and Where Did It Happen?

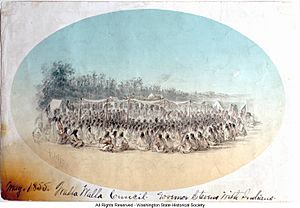

The Walla Walla Council began on May 29, 1855, and continued until June 11, 1855. The meetings took place in the scenic Walla Walla Valley, which is located in what is now the southeastern part of Washington State. This valley was chosen because it was a central and important location for many of the tribal nations involved, a place where they often gathered for trade, hunting, and social events.

Thousands of people gathered in the valley. It was a huge assembly, with tribal leaders, warriors, families, and U.S. officials all present. It was a time of great hope for some, and great concern for others, as the future of vast lands and many people was being decided.

Who Were the Main People Involved?

The council brought together a fascinating mix of leaders, each with their own goals and responsibilities.

The Tribal Nations: Guardians of the Land

The Native American groups at the council were not just "tribes" in a simple sense; they were sovereign tribal nations. This means they were independent, with their own governments, laws, leaders, and ways of life, just like separate countries. They had lived on these lands for countless generations, developing deep connections to the rivers, mountains, and plains.

- Cayuse: A skilled horse-riding people, known for their bravery and extensive trading networks throughout the region. Their territory stretched across parts of what is now Oregon and Washington.

- Nez Perce: One of the largest and most powerful nations, famous for their expert horsemanship and vast territories that included parts of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. They called themselves Nimíipuu, meaning "The People." Their leaders, like Chief Lawyer, played a significant role in the negotiations.

- Umatilla: Closely related to the Cayuse and Walla Walla, they shared cultural traditions and lived along the Columbia River and its tributaries. They were known for their fishing and gathering traditions.

- Walla Walla: Their name means "many waters," referring to the rivers in their homeland. They were also skilled traders and horsemen, with territory near the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers. Their respected leader, Chief Peo-peo-mox-mox, was a prominent voice at the council.

- Yakama: A large confederation of tribes and bands, known for their strong leadership and control over important fishing and hunting grounds in the Cascade Mountains and Columbia Plateau. Chief Kamiakin was a powerful and influential leader of the Yakama, deeply concerned about the future of his people's lands.

These leaders spoke for their people, carrying the weight of their ancestors' traditions and their descendants' future. They understood the importance of the land not just for survival, but for their identity and spiritual well-being.

Governor Isaac I. Stevens: The U.S. Representative

Representing the United States government was Isaac I. Stevens. He was a very important person at the time because he was the first governor of the Washington Territory. A "territory" is like a part of a country that isn't yet a full state; it's still being organized by the federal government. Governor Stevens had a big job: he was tasked with making treaties with the Native American tribes to open up land for American settlers, to build roads, and to plan for future railroads. He was a determined and ambitious man, eager to fulfill his mission and acquire vast amounts of land for the United States. He believed it was his duty to expand American control over the region.

The Treaties of 1855: Promises and Land

During the Walla Walla Council, after many days of intense discussions, speeches, and negotiations, several treaties were signed on June 9, 1855. These treaties were incredibly important because they set out new rules for how the land would be shared and how the different groups would live together.

Here's what the treaties generally said:

- Ceding Vast Lands

The tribal nations agreed to cede (which means to give up or hand over) enormous amounts of their traditional lands to the United States government. Governor Stevens was very successful in this, acquiring an astonishing 45,000 square miles (or about 120,000 square kilometers) of land. To give you an idea, that's bigger than the entire state of Pennsylvania! For the tribal nations, this was a monumental sacrifice, giving up ancestral lands that had sustained them for thousands of years. They believed they were doing so in exchange for lasting peace and security.

- Creating Reservations

In exchange for giving up so much land, the United States promised to set aside specific, smaller areas of land for the tribal nations to live on permanently. These areas are called reservations. The idea was that these reservations would be places where the tribal nations could continue their traditional ways of life, hunt, fish, gather food, practice their spiritual beliefs, and govern themselves without interference from settlers. They were meant to be permanent homelands.

- Land Distribution

The treaties tried to be fair, at least in theory, by giving larger portions of land to the two largest and most powerful nations: the Yakama and the Nez Perce. These reservations were designed to include most of their traditional hunting grounds, important fishing spots, and sacred places. The smaller nations, like the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla, were moved to a smaller, shared reservation, which became known as the Umatilla Reservation. The three main reservations established were the Nez Perce Reservation, the Umatilla Reservation, and the Yakama Reservation.

- Other Promises

Besides land, the treaties also included many other promises from the U.S. government. These included regular payments (called "annuities") of money and goods, the establishment of schools for children, blacksmith shops for repairs, mills for grinding grain, and the provision of farmers, doctors, and other services to help the tribal nations adjust to the new arrangements and develop new skills. These promises were crucial for the tribal nations, as they were giving up their traditional means of support.

Ratification: Making it Official

Even after the treaties were signed by the tribal leaders and Governor Stevens, they weren't immediately official. In the United States system, important treaties like these need to be approved by the U.S. Senate. This process is called ratification. It took four long years for the Senate to ratify these treaties, finally doing so in 1859. This delay caused a lot of uncertainty, frustration, and even anger for the tribal nations, as settlers began moving onto their lands even before the agreements were fully approved by the U.S. government.

Why Were These Treaties So Important?

The Walla Walla Council treaties were some of the earliest and most significant treaties made in the Pacific Northwest. They were meant to "codify" (which means to write down and make official) the "constitutional relationship" between the people living on the new Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Yakama reservations and the United States. In simpler terms, they were supposed to create a set of clear rules and understandings for how everyone would interact and share the land going forward. They legally established the boundaries of these reservations, which are still important today as the homelands of these sovereign nations. These treaties are still considered living documents by the tribal nations, defining their rights and relationship with the U.S. government.

Broken Promises: A Sad Chapter

Sadly, the story of the Walla Walla Council treaties doesn't end with everyone living happily ever after. The United States government, despite signing these solemn agreements and making these grand promises, later violated (which means broke) many of its commitments. This led to immense hardship and conflict.

Failure to Pay

One of the first and most significant violations was the government's failure to pay the agreed-upon sums of money and provide the promised goods and services to the tribal nations for the land they had given up. This left the tribal nations without the resources they had been promised to help them adapt to life on the reservations.

Shrinking Reservations

Even worse, the government later drastically reduced the size of some of the reservations. For example, the Nez Perce reservation was cut by a shocking 90%! This meant that lands that had been promised to them forever, lands that were vital for their hunting, fishing, gathering, and spiritual practices, were taken away. This was often done to open up land for gold miners or more settlers, completely disregarding the original treaty agreements.

Forcible Removal

In some cases, tribal members were even forcibly removed from their homes and lands that had been affirmed by the 1855 treaty. This was a devastating experience, tearing families and communities away from their ancestral homes and sacred sites, causing deep trauma and loss.

These broken promises led to deep distrust, immense hardship, and a sense of betrayal for the tribal nations. They had given up so much based on the word of the U.S. government, only to see those words disregarded.

What Happened Next? A Time of Conflict

The breaking of these treaties and the continued pressure on Native American lands led to a period of intense conflict in the Pacific Northwest. These wars were a direct result of the broken promises, the influx of settlers, and the struggle for land and sovereignty.

Cayuse War (1847–1855)

This war actually started before the Walla Walla Council, but its end coincided with the council. It was a conflict between the Cayuse people and the United States, sparked by cultural misunderstandings, the devastating impact of diseases brought by settlers, and growing land disputes.

Yakima War (1855–1858)

Almost immediately after the Walla Walla Council, tensions boiled over into the Yakima War. The Yakama people, feeling betrayed by the broken promises and the rapid influx of miners onto their lands (which were supposed to be protected), fought bravely to protect their territory and way of life.

Palouse War (1858)

This was another conflict that grew out of the Yakima War, involving the Palouse people and their allies, who resisted the U.S. military's expansion and the continued encroachment on their lands.

Nez Perce War (1877)

Perhaps one of the most famous and tragic conflicts, the Nez Perce War occurred many years after the Walla Walla Council. It began when a band of Nez Perce, led by the renowned Chief Joseph, refused to be moved from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley (which had been guaranteed by the original 1855 treaty but later taken away). They attempted a long and courageous journey of over 1,100 miles to escape to Canada, hoping to find freedom, but were eventually caught just short of the border.

These wars highlight the tragic consequences of broken treaties and the immense suffering caused when promises are not kept, and when one group's rights and lands are not respected.

Legacy of the Walla Walla Council

Even though the Walla Walla Council happened in 1855, its impact is still felt today. The treaties, even with their violations, are foundational documents for the tribal nations of the Pacific Northwest. They are a powerful reminder of the historical relationship between these sovereign nations and the United States.

Today, the descendants of the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama peoples continue to live on their reservations, working tirelessly to preserve their unique cultures, languages, and traditions. They also continue to advocate for their treaty rights, reminding the U.S. government of the promises made long ago. The story of the Walla Walla Council is a powerful lesson in history about promises, land, and the importance of respecting agreements between different peoples. It teaches us about the incredible resilience of Native American nations and their ongoing journey towards justice, self-determination, and understanding.