Cascade Range facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cascade Range |

|

|---|---|

| Cascade Mountains (in Canada) "The Cascades" |

|

The Cascades in Washington, with Mount Rainier, the range's highest mountain, standing at 14,411 ft (4,392 m). Seen in the background (left to right) are Mount Adams, Mount Hood, and Mount St. Helens.

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Rainier (Washington) |

| Elevation | 14,411 ft (4,392 m) NAVD 88 |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 700 mi (1,100 km) north-south |

| Width | 80 mi (130 km) |

| Geography | |

| Country |

|

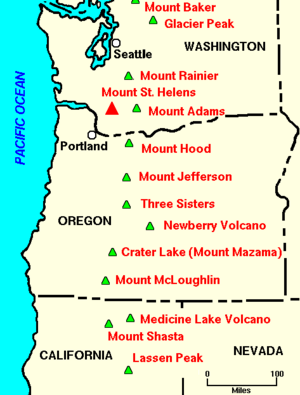

The Cascade Range, often called the Cascades, is a huge chain of mountains in western North America. It stretches from southern British Columbia in Canada, through the states of Washington and Oregon, all the way to northern California in the United States. This amazing range includes both regular mountains and famous volcanoes, which are sometimes called the High Cascades. The part of the range in British Columbia is known as the Canadian Cascades. The tallest mountain here is Mount Rainier in Washington, standing at 14,411 feet (4,392 meters) high.

The Cascades are a key part of the Pacific Ocean's Ring of Fire. This "Ring" is a huge circle of volcanoes and mountains around the Pacific Ocean, known for lots of volcanic activity. In the last 200 years, all volcanic eruptions in the main part of the United States have happened in the Cascade Volcanoes. Two well-known eruptions were Lassen Peak from 1914 to 1921 and a big eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980. Mount St. Helens also had smaller eruptions later, most recently from 2004 to 2008. The Cascade Range is part of the larger American Cordillera, which is a long chain of mountains forming the western "backbone" of North, Central, and South America.

Many beautiful national parks and protected areas are found in the Cascades. These include North Cascades National Park, Mount Rainier National Park, Crater Lake National Park, and Lassen Volcanic National Park. The northern part of the famous Pacific Crest Trail also winds its way through these mountains.

Contents

Exploring the Cascade Mountains

The Cascade Range begins in the south at Lassen Peak in northern California. It stretches north to where the Nicola River and Thompson River meet in British Columbia, Canada. In Canada, the Fraser River separates the Cascades from the Coast Mountains. In Oregon, the Willamette Valley separates them from the Oregon Coast Range.

Towering Peaks: The High Cascades

The tallest volcanoes in the Cascades are called the High Cascades. They stand out dramatically, often twice as tall as the mountains around them. These peaks can rise a mile or more above nearby ridges. The highest mountains, like Mount Rainier at 14,411 feet (4,392 meters), can be seen from 50 to 100 miles (80 to 160 kilometers) away!

Rugged North and Canadian Cascades

North of Mount Rainier, the range is known as the North Cascades in the United States. In Canada, it's called the Cascade Mountains, reaching up to Lytton Mountain. Both the North Cascades and Canadian Cascades are very rugged. Even the smaller peaks are steep and covered in glaciers. The valleys are quite low compared to the peaks, creating dramatic changes in height. The southern Canadian Cascades, especially the Skagit Range, look a lot like the North Cascades. However, the northern parts are less icy and more like a plateau.

Weather and Plant Life in the Cascades

The Cascades are close to the Pacific Ocean and get a lot of wind from the west. This brings significant rain and snowfall, especially on the western slopes. This happens because the mountains force the moist air upwards, a process called orographic lift. Some areas can get up to 1,000 inches (25 meters) of snow each year! Mount Baker in Washington holds a national record for snowfall, with 1,140 inches (29 meters) in the winter of 1998–99. It's common for places in the High Cascades to have over 500 inches (13 meters) of snow annually, so many peaks are white with snow and ice all year.

The western slopes are covered with thick forests of Douglas-fir, western hemlock, and red alder. The eastern slopes are drier and mostly have ponderosa pine, with some western larch, mountain hemlock, and subalpine fir at higher elevations. The eastern foothills get very little rain, sometimes as low as 9 inches (230 mm) a year, due to a "rain shadow" effect created by the mountains blocking the moisture.

The Columbia River Gorge

East of the Cascades, you'll find a dry plateau. This area was formed millions of years ago by many flows of volcanic rock from the Columbia River Basalt Group. These lava flows created the huge Columbia Plateau, covering 200,000 square miles (520,000 square kilometers) in eastern Washington, Oregon, and parts of Idaho.

The Columbia River Gorge is the only major break in the Cascade Range in the United States. About 7 million years ago, when the Cascades began to rise, the Columbia River already flowed through the area. As the mountains grew, the river was powerful enough to keep cutting its way through, creating the deep gorge we see today. This gorge also shows layers of ancient volcanic rock that were lifted and bent by the rising mountains.

A Look Back: History of the Cascades

Long before European explorers arrived, Native American tribes lived in the Cascade Range. They gave names to many of the peaks. For example, Mount Jefferson (Oregon) was called "Seekseekqua," Mount McLoughlin was "M'laiksini Yaina," and Mount Rainier was "Tahoma" in the Lushootseed language. Mount St. Helens was known as "Louwala-Clough," meaning "smoking mountain."

Early European Explorers and Names

In early 1792, British explorer George Vancouver sailed into Puget Sound. He gave English names to the tall mountains he saw. Mount Baker was named after his third lieutenant, Joseph Baker. However, a Spanish explorer, Manuel Quimper, had seen it earlier in 1790 and called it la gran montaña del Carmelo. Vancouver named Mount Rainier after Admiral Peter Rainier. Later that year, Vancouver's lieutenant, William Robert Broughton, explored the lower Columbia River. He named Mount Hood after Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood, a British admiral. Vancouver himself saw Mount St. Helens in May 1792 and named it after Alleyne FitzHerbert, 1st Baron St Helens, a British diplomat.

Vancouver's expedition didn't name the entire mountain range. He simply called it the "eastern snowy range." Earlier Spanish explorers had called it Sierra Nevada, which means "snowy mountains."

Lewis and Clark's Journey

In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Cascades along the Columbia River. For many years, this was the only practical way to cross that part of the mountains. They were the first non-Native Americans to see Mount Adams, though they mistakenly thought it was Mount St. Helens. Later, when they saw Mount St. Helens, they thought it was Mount Rainier. On their way back, Lewis and Clark saw a tall, snowy peak in the distance. They named it Mount Jefferson after the U.S. President who sponsored their trip. Lewis and Clark called the entire Cascade Range the "Western Mountains."

How the Cascades Got Their Name

The Lewis and Clark expedition, and the many settlers and traders who followed, faced a final challenge at the Cascades Rapids in the Columbia River Gorge. These rapids are now underwater, beneath the Bonneville Reservoir. Soon, people started calling the big, snow-capped mountains above these rapids the "mountains by the cascades." Eventually, this was shortened to simply "the Cascades." The first time the name "Cascade Range" was written down was by botanist David Douglas in 1825.

Early Crossings and Trails

In 1814, Alexander Ross, a fur trader, explored and crossed the northern Cascades. He was looking for a good route between Fort Okanogan and Puget Sound. He was likely the first European-American to explore the Methow River and Stehekin River areas. Because the northern Cascades were so difficult to cross and didn't have many beavers for fur, few fur traders explored them after Ross.

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) set up a major trading post at Fort Vancouver (near today's Portland, Oregon). From there, HBC trappers explored the Cascades, looking for animals. In the 1820s and 1830s, HBC trappers were the first non-Native Americans to explore the southern Cascades. They created trails near places like Crater Lake, Mount McLoughlin, Medicine Lake Volcano, Mount Shasta, and Lassen Peak.

Settling the Region

In 1845, the Barlow Road became the first established land route for U.S. settlers through the Cascade Range. It was the final overland part of the Oregon Trail. Before this road, settlers had to raft down the dangerous rapids of the Columbia River. The Barlow Road left the Columbia River near what is now Hood River, Oregon. It passed south of Mount Hood, near Government Camp, Oregon, and ended in Oregon City. This road was a successful toll road, costing $5 per wagon.

Another route, the Applegate Trail, was created to help settlers avoid the Columbia River rapids. This trail followed part of the California Trail into north-central Nevada. From there, it went northwest into northern California and then towards today's Ashland, Oregon. Settlers then traveled north along the existing Siskiyou Trail into the Willamette Valley.

Modern Developments and Volcanic Activity

Today, several major highways and rail lines cross the Cascades. While some lower areas have seen logging, much of the northern Cascades, from Mount Rainier northward, remains wild. These areas are protected by U.S. national parks and British Columbia provincial parks, like E.C. Manning Provincial Park.

The Canadian side of the range has its own history, including the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858–60. The Canadian Pacific Railway built a southern mainline through the Coquihalla River passes. This was one of the steepest and snowiest routes in the entire Pacific Cordillera. Near Hope, British Columbia, the old railway roadbed and the Othello Tunnels are now popular for hiking and biking. The Coquihalla Highway now uses this pass, connecting the coast to the interior of British Columbia.

Except for the 1915 eruption of Lassen Peak in northern California, the range was quiet for over a century. Then, on May 18, 1980, the dramatic eruption of Mount St. Helens brought worldwide attention to the Cascades. Geologists worried that this eruption might mean other long-sleeping Cascade volcanoes could become active again. Between 1800 and 1857, eight volcanoes erupted. No major eruptions have happened since Mount St. Helens, but scientists are taking precautions. For example, the Cascades Volcano Observatory and the Mount Rainier Volcano Lahar Warning System in Pierce County, Washington, help monitor these powerful mountains.

How the Cascades Were Formed

The Cascade Range is made up of thousands of small, short-lived volcanoes. These volcanoes have built a large platform of lava and volcanic rock over time. Rising above this platform are a few very large and famous volcanoes, like Mount Hood and Mount St. Helens, which truly stand out in the landscape.

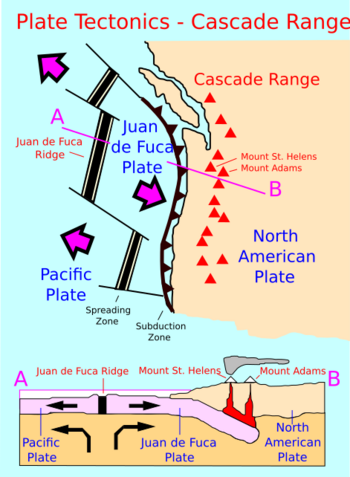

The Pacific Ring of Fire

The Cascade volcanoes are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. This is a huge circle of volcanoes that surrounds the Pacific Ocean. The Ring of Fire is also known for frequent earthquakes. Both the volcanoes and earthquakes happen for the same reason: subduction.

Understanding Subduction

Subduction is when one of Earth's large tectonic plates slides underneath another. In the Cascades, the dense Juan de Fuca Plate is slowly sliding beneath the North American Plate. This happens at a place called the Cascadia subduction zone. As the oceanic plate sinks deep into the Earth, the high heat and pressure cause water trapped in its rocks to escape. This water rises into the soft rock above the sinking plate, causing some of that rock to melt. This melted rock, called magma, then rises towards the Earth's surface and erupts, forming the chain of volcanoes we call the Cascade Volcanic Arc.

How People Use the Cascades

The soil around volcanoes is often very good for farming. This is because volcanic rocks contain important minerals like potassium, and they break down easily. Volcanic debris, like mudflows called lahars, also helps spread these mineral-rich materials. The snow and ice on the mountains store water, which is also important for farming.

Fun and Energy from the Mountains

Snow-capped mountains like Mount Hood and Mt. Bachelor are popular ski resorts in winter. In summer, they become great places for hiking and mountaineering. Much of the melting snow and ice flows into reservoirs. This water is used for fun activities like boating, and its power is captured to create hydroelectric power. After generating electricity, the water is then used to water crops.

Because there are so many powerful streams, many of the major rivers flowing west from the Cascades have been dammed. These dams create hydroelectric power. For example, Ross Dam on the Skagit River creates a reservoir that crosses the border into Canada. Near Concrete, Washington, the Baker River is dammed to form Lake Shannon and Baker Lake.

Geothermal Energy Potential

The Cascades also have a lot of untapped geothermal power potential. This means using heat from inside the Earth. The U.S. Geological Survey is studying this potential. Some of this energy is already being used in places like Klamath Falls, Oregon. There, volcanic steam heats public buildings. The highest underground temperature recorded in the range was 510°F (266°C) at 3,075 feet (937 meters) below the Newberry Volcano's caldera floor.

Plants and Animals of the Cascades

Most of the Cascade Range is covered by forests of large, cone-bearing trees. These include western red cedars, Douglas-firs, western hemlocks, firs, pines, and spruces. The cool, wet winters and warm, dry summers (thanks to the ocean's influence) are perfect for these evergreen trees. Mild temperatures and rich soils help them grow quickly and for a long time.

Diverse Habitats and Wildlife

As you travel through the Cascade Range, the climate changes. It gets colder as you go higher, then warmer and drier on the eastern side. Most lower and middle elevations have thick coniferous forests. Higher up, you'll find large meadows, alpine tundra (a treeless area), and glaciers. The southern Cascades are part of the California Floristic Province, an area with many different kinds of plants and animals.

Silver fir trees grow mostly above 2,500 feet (760 meters). Between 4,500 and 6,000 feet (1,370 to 1,830 meters) on the west side, you'll see moors, meadows, and groves of mountain hemlock and subalpine fir. The treeline (where trees stop growing) is around 6,000 feet (1,830 meters). On the east side, subalpine forests of larch trees gradually change to pine and interior fir forests below 4,200 feet (1,280 meters). Below 2,500 feet (760 meters), these turn into ponderosa forests, which then become semidesert scrub closer to sea level. Above 7,500 feet (2,290 meters), the landscape is mostly bare, with only moss and lichen growing.

Animals of the Cascades

Many animals call the Cascades home. These include black bears, coyotes, bobcats, cougars, beavers, deer, elk, moose, mountain goats, and a few wolf packs that have returned from Canada. There are also fewer than 50 grizzly bears living in the Cascades of Canada and Washington.

See also

In Spanish: Cordillera de las Cascadas para niños

In Spanish: Cordillera de las Cascadas para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |