North Cascades facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Cascades |

|

|---|---|

| Canadian Cascades | |

Mount Shuksan, one of the most picturesque peaks of the North Cascades

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Baker |

| Elevation | 3,286 m (10,781 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 434.5 km (270.0 mi) North-South |

| Width | 241 km (150 mi) East-West |

| Geography | |

| Countries | Canada and United States |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

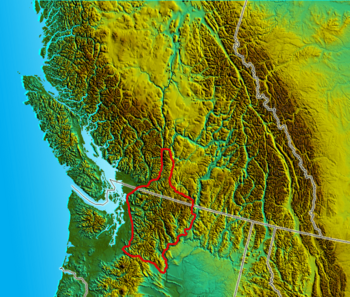

The North Cascades are a big mountain range in western North America. They stretch across the border between the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. state of Washington. In both countries, they are officially called the Cascade Mountains. The part of the range in Canada is often called the Canadian Cascades by people in the U.S. This name also includes mountains near the Fraser Canyon up to the town of Lytton.

Most of these mountains are not volcanoes. However, they do include a few stratovolcanoes like Mount Baker, Glacier Peak, and Coquihalla Mountain. These are part of the larger Cascade Volcanic Arc.

Contents

- Exploring the North Cascades' Geography

- Exploring the North Cascades' Subranges

- Notable Peaks of the North Cascades

- Tallest Waterfalls in the North Cascades

- Geology of the North Cascades

- Ecology: Plants and Animals of the North Cascades

- History of the North Cascades

- Climbing in the North Cascades

- Protected Areas in the North Cascades

- See also

Exploring the North Cascades' Geography

The U.S. part of the North Cascades and the nearby Skagit Range in British Columbia are famous for their amazing views. They are also known for challenging mountaineering (mountain climbing). This is because the mountains are very steep and rugged. Most peaks are under 10,000 feet (3,000 m) tall. But the valleys below are very low, making the mountains look much taller. The difference in height between the valley floor and the peak can be over 6,000 feet (1,800 m).

The summits of the Canadian Cascades are not as icy. They have rock "horns" that stick up from flat, high areas. Areas like Manning Park and Cathedral Park are known for their wide alpine meadows (high mountain grasslands). The eastern side of the U.S. part of the range also has these meadows. Some areas on the U.S. side are protected as part of North Cascades National Park.

The western part of the range gets a lot of rain and snow. This leads to many glaciers. Along with the land slowly pushing up (called tectonic uplift), this creates a dramatic landscape. Deep, U-shaped valleys were carved by glaciers long ago. Sharp ridges and peaks were shaped by more recent snow and ice.

The eastern and northern parts of the range are flatter, like a plateau. But in the northernmost areas, there are deep valleys along the side of the Fraser Canyon. One notable valley is that of the Anderson River.

Where are the North Cascades Located?

The Fraser River and the flat land south of it form the northern border of the range. To the east, the Okanogan River and the Columbia River mark the boundary in the United States. The northeastern border goes from the Thompson River to the Similkameen River. To the west, the mountains meet the Puget Sound. This is a narrow coastal plain, except near Chuckanut Drive where the mountains touch the Sound directly.

The southern border of the North Cascades is not as clear. For this article, we will say it is U.S. Highway 2, which crosses Stevens Pass. This also includes the Skykomish River, Nason Creek, and the lower Wenatchee River. This idea matches how Fred Beckey described the area in his Cascade Alpine Guide. Sometimes, the southern border is thought to be Snoqualmie Pass and Interstate 90. Some people even use "North Cascades" to mean the entire mountain range north of the Columbia River.

Geologically, the rocks of the North Cascades extend south past Stevens Pass. They also go west into the San Juan Islands. The exact boundaries with other geological areas, like the Okanagan Highland to the east and the Interior Plateau and Coast Mountains to the north, are still debated.

Understanding the North Cascades' Climate

The climate in the North Cascades changes a lot depending on the location and height. The western side of the mountains is wet and cool. It gets 60 to 250 inches (1.5 to 6.4 m) of rain and snow each year. This creates a temperate rain forest climate in the low valleys. Higher up, it changes to montane and alpine climates. Summers are quite dry, with much less rain than in winter. Sometimes, warm air from the east and cool air from the west meet over the Cascades in summer. This can cause thunderstorms.

The eastern side of the mountains is in a rain shadow. This means it is much drier than the western side. Most winds and moisture come from the west. So, the eastern lowlands become semi-arid (very dry). Like most mountain areas, the amount of rain and snow increases a lot as you go higher. This is why there is so much winter snow and glaciation in the high North Cascades.

The eastern slopes and mountain passes can get a lot of snow. Cold air from the Arctic can flow south from British Columbia. It moves through the Okanogan River valley into the basin east of the Cascades. This cold air can get trapped in the lower passes, like Snoqualmie Pass and Stevens Pass. Milder, Pacific air moving east over the Cascades is often forced up by this trapped cold air. This means the passes often get more snow than higher areas in the Cascades. This effect makes it possible to have ski resorts at relatively low elevations, like Snoqualmie Pass (about 3,000 feet (910 m)) and Stevens Pass (about 4,000 feet (1,200 m)).

Exploring the North Cascades' Subranges

The North Cascades are made up of several smaller mountain groups, called subranges.

- North Cascades

- Skagit Range

- Chuckanut Mountains

- Entiat Mountains

- Chelan Mountains

- Methow Mountains (also called Sawtooth Ridge)

- Skagit River Group

- Canadian Cascades

- Skagit Range

- Hope Mountains

- Cheam Range

- Hozameen Range

- Okanagan Range

- Coquihalla Range (this name is not official)

- Llamoid Group (this name is not official)

- Anderson River Group (this name is not official)

- Skagit Range

Notable Peaks of the North Cascades

Here are some of the tallest peaks in the North Cascades:

| Mountain | Height | Coordinates | Prominence | Parent mountain | First ascent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ft) | (m) | (ft) | (m) | ||||

| Mount Baker | 10,778 | 3,285 | 48°46′N 121°48′W / 48.767°N 121.800°W | 8,881 | 2,707 | Mount Rainier | 1868 by Edmund T. Coleman and party |

| Glacier Peak | 10,541 | 3,213 | 48°6′45.05″N 121°6′49.70″W / 48.1125139°N 121.1138056°W | 7,501 | 2,286 | Mount Rainier | 1898 by Thomas Gerdine |

| Bonanza Peak | 9,511 | 2,899 | 48°14′16″N 120°51′58″W / 48.23778°N 120.86611°W | 3,711 | 1,131 | Glacier Peak | 1937 by Curtis James, Barrie James, Joe Leuthold |

| Mount Fernow | 9,249 | 2,819 | 48°09′44″N 120°48′30″W / 48.16222°N 120.80833°W | 2,809 | 856 | Bonanza Peak | 1932 by Oscar Pennington, Hermann Ulrichs |

| Goode Mountain | 9,220 | 2,810 | 48°28′58″N 120°54′39″W / 48.48278°N 120.91083°W | 3,800 | 1,200 | Bonanza Peak | 1936 by Wolf Bauer, Philip Dickett, Joe Halwax, Jack Hossack, George MacGowan |

(This table only lists peaks that stand out by at least 1,000 feet (300 m) from their surroundings.)

Some peaks are notable for how much they rise above the land around them:

| Mountain | Height | Prominence | Parent mountain | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ft) | (m) | (ft) | (m) | ||

| Mount Baker | 10,778 | 3,285 | 8,881 | 2,707 | Mount Rainier |

| Glacier Peak | 10,541 | 3,213 | 7,501 | 2,286 | Mount Rainier |

| Round Mountain | 5,320 | 1,620 | 4,780 | 1,460 | Three Fingers |

| Mount Spickard | 8,979 | 2,737 | 4,779 | 1,457 | Mount Baker |

| Welch Peak | 7,976 | 2,431 | 4,728 | 1,441 | Robinson Mountain |

| Three Fingers | 6,850 | 2,090 | 4,490 | 1,370 | Glacier Peak |

| Mount Shuksan | 9,131 | 2,783 | 4,411 | 1,344 | Mount Baker |

| Remmel Mountain | 8,684 | 2,647 | 4,370 | 1,330 | Mount Lago |

| Mount Prophet | 7,650 | 2,330 | 4,080 | 1,240 | Luna Peak |

| Mount Outram | 8,074 | 2,461 | 3,678 | 1,121 | Hozomeen Mountain |

| Mount Lago | 8,743 | 2,665 | 3,300 | 1,000 | Silver Star Mountain |

These peaks are known for their steep rise from the local land:

| Mountain | Height | |

|---|---|---|

| (ft) | (m) | |

| Mount Baker | 10,778 | 3,285 |

| Glacier Peak | 10,541 | 3,213 |

| Goode Mountain | 9,220 | 2,810 |

| Mount Shuksan | 9,127 | 2,782 |

| Jack Mountain | 9,066 | 2,763 |

| North Gardner Mountain | 8,956 | 2,730 |

| Mount Redoubt | 8,956 | 2,730 |

| Eldorado Peak | 8,876 | 2,705 |

| Luna Peak | 8,311 | 2,533 |

| Johannesburg Mountain | 8,220 | 2,510 |

| Agnes Mountain | 8,115 | 2,473 |

| Hozomeen Mountain | 8,066 | 2,459 |

| Slesse Mountain | 8,002 | 2,439 |

| American Border Peak | 7,994 | 2,437 |

| Mount Blum | 7,680 | 2,340 |

| Sloan Peak | 7,835 | 2,388 |

| Colonial Peak | 7,771 | 2,369 |

| Mount Triumph | 7,270 | 2,220 |

| Pugh Mountain | 7,201 | 2,195 |

| Davis Peak | 7,051 | 2,149 |

| Whitehorse Mountain | 6,850 | 2,090 |

| Baring Mountain | 6,125 | 1,867 |

Tallest Waterfalls in the North Cascades

- Further information: Waterfalls of the North Fork Cascade River Valley

The North Cascades are famous for their many very tall waterfalls. These waterfalls are fed by melting glaciers. Here are the ten highest measured waterfalls:

| Waterfall | Height | Stream | Location | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ft) | (m) | ||||

| Colonial Creek Falls | 2,584 | 788 | Colonial Creek | Diablo Lake | 48°40′13″N 121°08′26″W / 48.67023°N 121.14044°W |

| Johannesburg Falls | 2,465 | 751 | Unnamed | Below Johannesburg Peak, near Mount Torment | 48°28′36″N 121°05′29″W / 48.47655°N 121.09132°W |

| Sulphide Creek Falls | 2,182 | 665 | Sulphide Creek | Eastern boundary of North Cascades National Park | 48°47′47″N 121°34′32″W / 48.79647°N 121.57563°W |

| Silver Lake Falls | 2,128 | 649 | Silver Creek | Near Mount Spickard in North Cascades National Park | 48°59′21″N 121°13′22″W / 48.98917°N 121.22278°W |

| Blum Basin Falls | 1,680 | 510 | Blum Creek | Below Mount Blum | 48°44′01″N 121°30′09″W / 48.73368°N 121.50263°W |

| Boston Creek Falls | 1,627 | 496 | Boston Creek | Near North Fork Cascade River | 48°29′35″N 121°04′32″W / 48.49298°N 121.07549°W |

| Torment Falls | 1,583 | 482 | Torment Creek | Near North Fork Cascade River | 48°29′50″N 121°06′22″W / 48.49719°N 121.10602°W |

| Green Lake Falls | 979 | 298 | Unnamed fork of Bacon Creek | Near Green Lake in North Cascades National Park | 48°41′34″N 121°29′34″W / 48.69271°N 121.49285°W |

| Depot Creek Falls | 967 | 295 | Depot Creek | Near Mount Redoubt, North Cascades National Park | 48°58′38″N 121°17′05″W / 48.97732°N 121.28477°W |

| Rainy Lake Falls | 800 | 240 | Unnamed | Rainy Lake, Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest | 48°29′49″N 120°44′45″W / 48.49694°N 120.74583°W |

Many tall waterfalls form where melting water from mountain glaciers drops down a steep rock face. This is common in the North Cascades. Many waterfalls, even if very tall, are not well-known because they are hard to see and do not carry much water. Seahpo Peak Falls, which is nearly 2,200 feet (670 m) tall, is one such example. However, some are very notable. Sulphide Creek Falls forms where meltwater from two large Mount Shuksan glaciers flows through a narrow channel. It then drops over a 2,183-foot (665 m) rock face at the start of Sulphide Valley.

Geology of the North Cascades

Most of the North Cascades are made of "deformed and changed, structurally complex pre-Tertiary rocks". These rocks came from different places around the world. The area is built from several different rock blocks, called terranes. These terranes have different ages and origins. They are separated by old fault lines. The most important one is the Straight Creek Fault. It runs north to south from north of Yale, British Columbia, through Hope, Marblemount, Washington, and down to Kachess Lake.

There is proof that this fault moved a lot in the past. Similar rocks on opposite sides of the fault are now miles apart. Scientists think this is because the West Coast of North America moved north compared to the rest of the continent.

About 35 million years ago, the oceanic crust from the Pacific Ocean began sliding under the continental margin. This process, called subduction, created the current volcanoes. It also formed many igneous (volcanic) rock bodies made of diorite and gabbro. The current lifting up of the Cascade Range started about 8 million years ago.

The rocks in the North Cascades are similar to those found north near Mount Meager massif in the Coast Mountains. This means the border between the North Cascades and Coast Mountains is not always clear.

In British Columbia, the western geological border of the North Cascades is the Fraser River. In the United States, the western border is the Puget Lowland. However, rocks similar to those in the North Cascades extend west into the San Juan Islands.

The eastern geological border of the North Cascades might be the Chewack-Pasayten Fault. This fault separates the easternmost part of the North Cascades, the Methow Terrane, from the Quesnellia Terrane. The fault also separates the Methow River valley from the Okanagan Range. The Columbia River Basalt Group forms the southeastern border of the North Cascades.

The southern limit of the "North Cascades" in terms of geology can be defined in different ways. It might be where the igneous and metamorphic rocks stop appearing. This is generally north of Snoqualmie Pass. It could also be Snoqualmie Pass itself, or Naches Pass at the White River Fault Zone.

Glaciers in the North Cascades

Alpine glaciers are a key feature of the entire Cascade Range. But they are especially common in the North Cascades. The stratovolcanoes like Mount Baker and Glacier Peak have the largest and most obvious glaciers. However, many smaller, non-volcanic peaks also have glaciers. For example, the part of the Cascades north of Snoqualmie Pass (which is roughly the North Cascades) has many glaciers.

These glaciers all shrunk between 1900 and 1950. From 1950 to 1975, many North Cascades glaciers grew again, but not all of them. Since 1975, the shrinking has become faster. By 1992, all 107 monitored glaciers were getting smaller. The year 2015 was very bad for Cascadian Glaciers. They lost an estimated five to ten percent of their mass. This was the biggest loss in over 50 years. There are about 700 glaciers in the range, but some have already disappeared.

Since a short period of growth in the 1950s, most of these glaciers have been shrinking. This is a big worry for water managers in the area. The glaciers and winter snowpack act like a large water storage. As snow and ice melt in the summer, this meltwater makes up for less rain. As glaciers shrink, they will provide less water in the summer.

The Cascades north of Snoqualmie Pass have 756 glaciers. They cover 103 square miles (270 km2) of land. To compare, the entire contiguous United States has about 1,100 glaciers in total. These cover 205 square miles (530 km2).

Ecology: Plants and Animals of the North Cascades

The North Cascades has many different kinds of plants. It is home to more than 1630 types of vascular plants (plants with tubes for water). There are eight different life zones. Each zone supports thousands of plants in its own way. If you travel from west to east through the range, you would go through several different natural areas. First, it gets higher and colder. Then, it gets warmer but drier. Each of these areas can be described by a special tree that grows there, or by a lack of trees. These include Western hemlock, silver fir, subalpine mountain hemlock, Alpine tundra (no trees), subalpine fir, and grand fir/Douglas-fir.

The range also has many different animals. These include bald eagles, wolves, grizzly bears, mountain lions, and black bears. At least 75 types of mammals and 200 types of birds live in or pass through the North Cascades. There are also 11 types of fish on the west side of the Cascades. Examples of amphibians (like frogs and salamanders) found here include the western toad (Bufo boreas) and the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa).

The variety of life in this area is at risk from global climate change. It is also threatened by exotic plant species that are not native to the area. These non-native plants grow well near human-made things like roads and trails. Examples of these invasive plants are the diffuse knapweed (Centaurea diffusa) and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea).

History of the North Cascades

On the U.S. side of the border, early people living in the North Cascades included the Nooksack, Skagit, and Sauk-Suiattle tribes in the west. The Okanagan people lived on the eastern side. The Nlaka'pamux people from what is now Canada hunted in the heart of the range, even south into Washington. The tribes living and using the range on the Canadian side were the Nlaka'pamux, Sto:lo, and the Upper and Lower Similkameen groups of the Okanagan. Many names of places in the region today come from native words.

Fur traders came to the area in the early 1800s. They came from Canada and from Astoria on the Columbia River. One of the first was Alexander Ross in 1814. After the border was set at the 49th Parallel, the Hudson's Bay Company had to find new trade routes. They tried a route over the northern Canadian Cascades, but it was too difficult and soon abandoned. Later routes, like the Dewdney Trail, helped build modern roads. South of the border, people looked for places to build railroads and found mines.

Miners played a big role in exploring the range from the 1880s to the early 1900s. For example, mines around the town of Monte Cristo produced a lot of silver and gold. The Holden Mine produced copper and gold. The discovery of gold by American prospectors near the Thompson River helped start the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858-1860. This led to the creation of the Colony of British Columbia. The gold rush also led to exploration of the Cascades east of the canyon. New towns like Boston Bar, Lytton, Hope, and Princeton, British Columbia were founded.

Early settlers also came to the foothills of the North Cascades in the late 1800s. They used the mountains for timber and grazing animals. However, the range is so rugged that this use was not as widespread as in other areas.

Early recreational use of the range included trips by local climbing clubs, The Mountaineers and The Mazamas. These groups did not fully explore the deepest parts of the range until the 1930s and 1940s. Most peaks in the most isolated areas were not climbed until the 1970s. This makes it one of the last explored mountain ranges in the United States.

Climbing in the North Cascades

Hikers and climbers often call the North Cascades the "American Alps." This is because of the many steep, jagged peaks that stretch across the range. The difficult paths and amazing mountain terrain make it a top training spot for mountain climbers.

Protected Areas in the North Cascades

The main protected area in Washington is North Cascades National Park. It covers much of the area between Mount Baker and the Cascade divide. Next to the park are Ross Lake National Recreation Area and Lake Chelan National Recreation Area. Other protected wilderness areas in the range include:

- Mount Baker Wilderness

- Glacier Peak Wilderness

- Boulder River Wilderness

- Henry M. Jackson Wilderness,

- Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness

- Noisy-Diobsud Wilderness

- Pasayten Wilderness

- Stephen Mather Wilderness

- Wild Sky Wilderness

In British Columbia, protected areas include:

- Skagit Valley Provincial Park

- E.C. Manning Provincial Park

- Cascade Recreation Area

- Cathedral Provincial Park

- Sx̱ótsaqel/Chilliwack Lake Provincial Park

- Coquihalla Canyon Provincial Park

- Coquihalla Summit Recreation Area

See also

In Spanish: Cascadas del Norte para niños

In Spanish: Cascadas del Norte para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |