Mount St. Helens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mount St. Helens |

|

|---|---|

A 3,000-foot (0.9 km) high steam plume on May 19, 1982, two years after the big eruption in 1980

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 8,363 ft (2,549 m) |

| Prominence | 4,605 ft (1,404 m) |

| Listing | |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Alleyne FitzHerbert, 1st Baron St Helens |

| Native name | Error {{native name}}: an IETF language tag as parameter {{{1}}} is required (help) |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mount St. Helens |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Less than 40,000 years old |

| Mountain type | Active stratovolcano (Subduction zone) |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 2004–2008 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1853 by Thomas J. Dryer |

| Easiest route | Hike via south slope of volcano (closest area near eruption site) |

Mount St. Helens is an active volcano in Washington state, USA. It is known as Lawetlat'la by the Cowlitz people and Loowit or Louwala-Clough by the Klickitat. The volcano is about 52 miles (83 km) northeast of Portland, Oregon, and 98 miles (158 km) south of Seattle. Its English name comes from British diplomat Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens. He was a friend of explorer George Vancouver, who mapped the area in the late 1700s. Mount St. Helens is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, which is a section of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

The major eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980, was the deadliest and most costly volcanic event in U.S. history. Fifty-seven people lost their lives. Many homes, bridges, railways, and highways were destroyed. A huge landslide was caused by a magnitude 5.1 earthquake. This landslide led to a side-blast eruption. The mountain's top dropped from 9,677 feet (2,950 m) to 8,363 feet (2,549 m) high. It left a horseshoe-shaped crater about 1 mile (1.6 km) wide.

After the 1980 eruption, the volcano was active until 2008. Scientists believe future eruptions could be even more powerful. This is because of how the lava domes are shaped inside the volcano. Mount St. Helens is a popular place for hiking. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan and the U.S. Congress created the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. This area protects the volcano and its surroundings.

Contents

About Mount St. Helens

Where is Mount St. Helens?

Mount St. Helens is about 34 miles (55 km) west of Mount Adams. Both are in the western part of the Cascade Range. These two volcanoes are often called "brother and sister" mountains. They are about 50 miles (80 km) from Mount Rainier, the tallest volcano in the Cascades. Mount Hood in Oregon is about 60 miles (97 km) southeast of Mount St. Helens.

Mount St. Helens is quite young in terms of geology. It formed less than 40,000 years ago. The cone shape it had before the 1980 eruption started growing about 2,200 years ago. It is thought to be the most active volcano in the Cascades over the last 10,000 years.

Before 1980, Mount St. Helens was the fifth-highest peak in Washington. It looked very symmetrical and was covered in snow and ice. This led some people to call it the "Fuji-san of America." It had eleven named glaciers before 1980. Only the Shoestring Glacier has somewhat recovered since the eruption. The mountain rises over 5,000 feet (1,500 m) from its base. At its widest, the base is 6 miles (9.7 km) across.

Streams from the volcano flow into three main river systems. These are the Toutle River, the Kalama River, and the Lewis River. Heavy rain and snow feed these streams. The Lewis River has three dams that make hydroelectric power. The Swift Reservoir is directly south of the volcano's peak.

Mount St. Helens is in Skamania County, Washington. However, you can reach it through Cowlitz County to the west or Lewis County to the north. Washington State Route 504, also called the Spirit Lake Memorial Highway, connects to Interstate 5. This highway is 34 miles (55 km) west of the mountain. The closest town to the volcano is Cougar, about 11 miles (18 km) south-southwest of the peak. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest surrounds Mount St. Helens.

The Crater Glacier

After the 1980 eruption, a new glacier began to form during the winter of 1980–1981. It is now called Crater Glacier. This glacier grew quickly because of the shade from the crater walls and heavy snowfall. By 2004, it covered about 0.36 square miles (0.93 km2). It was split into two parts by a lava dome. The glacier often looks dark in late summer due to rocks falling from the crater walls and ash from small eruptions.

By 2006, the ice was about 300 feet (91 m) thick on average. In some places, it was as deep as 650 feet (200 m). This is almost as deep as the much older Carbon Glacier on Mount Rainier. Since all the ice formed after 1980, Crater Glacier is very young geologically. Yet, it has about the same amount of ice as all the glaciers that were there before 1980.

From 2004, new lava domes pushed the glacier parts aside and upward. The glacier's surface became very bumpy with cracks and icefalls. This was caused by the movement of the crater floor. The new domes have almost completely separated Crater Glacier into eastern and western parts. Even with the volcanic activity, the glacier has continued to grow. In May 2008, the two parts of the glacier joined, completely surrounding the lava domes. New glaciers have also formed on the crater walls above Crater Glacier. They feed rock and ice onto its surface.

How Mount St. Helens Formed (Geology)

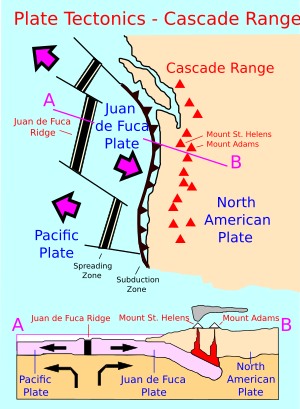

Mount St. Helens is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. This is a curved line of volcanoes that stretches from British Columbia to Northern California. It runs roughly parallel to the Pacific coastline. Underneath this area, a heavy ocean plate is slowly sliding beneath the North American plate. This process is called subduction.

As the ocean plate sinks deeper into the Earth, it gets very hot and experiences high pressure. Water trapped in the rocks escapes. This superheated water rises into the soft mantle above the sinking plate. This causes some of the mantle to melt, forming magma. This new magma then rises through cracks and faults in the Earth's crust. It also melts the surrounding rocks. This process changes the magma's chemical makeup. Some of this melted rock eventually reaches the surface and erupts, creating the volcanoes of the Cascade Volcanic Arc.

The magma for Mount St. Helens gathers in two chambers deep below the volcano. One is about 3 to 7 miles (5 to 12 km) down. The other is about 7 to 25 miles (12 to 40 km) deep. The deeper chamber might even be connected to Mount Adams.

Past Eruptions of Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens has had many eruptions over thousands of years. Scientists divide its history into different stages. The earliest stages are called "ancestral stages" (from about 40,000 to 8,000 years ago). The modern period, since about 2500 BC, is called the "Spirit Lake Stage." The main difference between these periods is the type of lava that erupted. Older lavas were a mix of dacite and andesite. Modern lavas are much more varied.

Mount St. Helens began to grow about 37,600 years ago. It started with eruptions of hot pumice and ash. Huge mudflows also flowed down the volcano. Mudflows have been a big part of all of St. Helens' eruption cycles. After these early periods, the volcano often had long quiet times.

Around 2500 BC, the "Smith Creek" period began. Large amounts of ash and pumice covered vast areas. An eruption in 1900 BC was the biggest known eruption from St. Helens in the last 10,000 years. Ash from this eruption reached as far as Mount Rainier National Park. It even reached parts of Alberta, Canada, and eastern Oregon.

The "Pine Creek" period started around 1200 BC. This period had smaller eruptions. Many hot, fast-moving flows of ash and gas, called pyroclastic flows, rushed down the volcano's sides. They settled in nearby valleys. A large mudflow partly filled 40 miles (64 km) of the Lewis River valley.

The "Castle Creek" period began around 400 BC. During this time, the lava changed, adding olivine and basalt. The cone shape of the mountain before 1980 started to form then. Large lava flows of andesite and basalt covered parts of the mountain. Some flowed up to 9 miles (14 km) away. Mudflows also moved down the Toutle and Kalama river valleys.

The "Sugar Bowl" period was short and unique. It produced the only known sideways blast from Mount St. Helens before the 1980 eruption. The volcano first erupted quietly, forming a dome. Then it erupted violently, sending out ash, blast deposits, pyroclastic flows, and mudflows.

Around 1480, after about 700 years of quiet, the "Kalama" period began. Large amounts of light gray pumice and ash erupted. The 1480 eruption was several times bigger than the 1980 event. Another large eruption in 1482 was similar in size to the 1980 eruption. Ash and pumice piled up 3 feet (0.91 m) thick northeast of the volcano. Even 50 miles (80 km) away, the ash was 2 inches (5.1 cm) deep. Mount St. Helens reached its greatest height and its very symmetrical shape by the end of this period, around 1647.

The "Goat Rocks" period started in 1800 and lasted 57 years. This was the first period with both spoken and written records. Like the Kalama period, it began with a blast of ash. This was followed by an andesite lava flow and then a dacite dome forming at the top. The 1800 eruption was probably as big as the 1980 eruption. However, it did not cause as much damage to the mountain's cone. Ash from this eruption drifted over Washington, Idaho, and Montana. There were at least a dozen small ash eruptions reported from 1831 to 1857. The Goat Rocks dome was destroyed in the May 18, 1980, eruption. This event removed the entire north face and the top 1,300 feet (400 m) of the mountain.

The 1980 Eruption and Later Activity

On March 20, 1980, Mount St. Helens had a magnitude 4.2 earthquake. On March 27, steam started coming out. By late April, the north side of the mountain began to bulge. On May 18, a second earthquake, magnitude 5.1, caused the north face of the mountain to collapse. This was the largest known debris avalanche ever recorded.

The magma inside St. Helens burst out in a huge pyroclastic flow. This flow flattened plants and buildings over an area of 230 square miles (600 km2). Over 1.5 million metric tons of sulfur dioxide gas were released into the air. On the Volcanic Explosivity Index scale, this eruption was rated a 5. It was a Plinian eruption, which means it had a tall, column-shaped ash cloud.

The collapse of the mountain's northern side mixed with ice, snow, and water. This created lahars, which are volcanic mudflows. These mudflows traveled many miles down the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers. They destroyed bridges and logging camps. About 3.9 million cubic yards (3 million m3) of material traveled 17 miles (27 km) south into the Columbia River.

For over nine hours, a strong plume of ash erupted. It reached 12 to 16 miles (19 to 26 km) above sea level. The ash cloud moved eastward at about 60 miles per hour (97 km/h). Ash reached Idaho by noon. The next morning, ash was found on cars and roofs as far away as Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

By about 5:30 p.m. on May 18, the ash column became smaller. Less severe eruptions continued through the night and for several days. The May 18 eruption released a huge amount of energy. It ejected more than 0.67 cubic miles (2.8 km3) of material. The loss of the mountain's north side reduced its height by about 1,300 feet (400 m). It left a crater 1.2 to 1.8 miles (1.9 to 2.9 km) wide and 2,084 feet (635 m) deep. The north end of the crater was a huge open breach.

The eruption killed 57 people. It also killed nearly 7,000 large animals like deer, elk, and bear. An estimated 12 million fish from a hatchery also died. More than 200 homes were destroyed or badly damaged. About 185 miles (298 km) of highways and 15 miles (24 km) of railways were also ruined.

Between 1980 and 1986, Mount St. Helens remained active. A new lava dome formed inside the crater. Many small explosions and dome-building eruptions happened. The mountain also erupted with large ash clouds in late 1989 to early 1990, and again in late 1990 to early 1991.

Mount St. Helens Activity from 2004 to 2008

Magma reached the surface of the volcano around October 11, 2004. This led to a new lava dome growing on the south side of the existing dome. This new dome continued to grow through 2005 and into 2006. Scientists observed temporary features, like a lava spine nicknamed the "whaleback." This was a long piece of hardened magma pushed up by pressure from below. These features were fragile and often broke apart. On July 2, 2005, the tip of the whaleback broke off. This caused a rockfall that sent ash and dust hundreds of meters into the air.

Mount St. Helens showed a lot of activity on March 8, 2005. A 36,000-foot (11,000 m) plume of steam and ash appeared. It was even visible from Seattle. This small eruption was a release of pressure from the growing dome. It happened along with a magnitude 2.5 earthquake.

Another feature that emerged from the dome was called the "fin" or "slab." This large, cooled volcanic rock was about half the size of a football field. It was being pushed upward as fast as 6 feet (1.8 m) per day. By mid-June 2006, the slab was crumbling from frequent rockfalls. However, it was still being pushed out. The dome's height was 7,550 feet (2,300 m). This was still lower than the height reached in July 2005 when the whaleback collapsed.

On October 22, 2006, a magnitude 3.5 earthquake caused a part of the dome, called Spine 7, to break off. The collapse sent an ash plume 2,000 feet (610 m) over the western rim of the crater. The ash plume quickly disappeared.

On December 19, 2006, a large white plume of steam was seen. Some news outlets thought it was a small eruption. However, the Cascades Volcano Observatory did not report any major ash plume. The volcano had been erupting continuously since October 2004. This eruption mainly involved the slow pushing out of lava, forming a dome in the crater.

On January 16, 2008, steam started leaking from a crack on top of the lava dome. The earthquakes that came with it were the strongest since 2004. Scientists stopped working in the crater and on the mountain's sides. However, the risk of a major eruption was thought to be low. By the end of January, the eruption stopped. No more lava was being pushed out. On July 10, 2008, it was decided that the eruption had ended. This was after more than six months of no volcanic activity.

Future Dangers from Mount St. Helens

Future eruptions of Mount St. Helens will likely be even bigger than the 1980 eruption. The way the lava domes are now in the crater means that much more pressure will be needed for the next eruption. This means the damage could be greater. A lot of ash could fall over 40,000 square miles (100,000 km2). This would disrupt transportation. A large lahar (mudflow) is also likely to flow down parts of the Toutle River. This could cause damage in towns along the I-5 highway.

Ecology: Life Around the Volcano

Before the 1980 eruption, the slopes of Mount St. Helens were covered in thick forests. These forests had lots of western hemlock, Douglas fir, and western redcedar. Higher up, Pacific silver fir trees grew. Near the treeline, there were mountain hemlock and Alaska yellow cedar. Large animals like Roosevelt elk, black-tailed deer, American black bear, and mountain lion lived there.

The treeline at Mount St. Helens was unusually low. This was because of past volcanic activity. Alpine meadows were rare. Mountain goats lived at higher elevations, but their population was wiped out by the 1980 eruption.

How the Eruption Changed Nature

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens has been studied more than any other eruption. This is because research started right after the eruption. Also, the eruption did not completely destroy all life in the area. More than half of all studies on how nature responds to volcanic eruptions come from Mount St. Helens.

An important idea from studying Mount St. Helens is "biological legacy." This means the living things that survive a huge natural disaster. They can be living plants, dead organic material, or patterns of life that existed before the event. These survivors greatly influence how nature rebuilds itself after the disturbance.

Some species from every level of the food web survived the 1980 eruption. This allowed food webs to rebuild fairly quickly. Larger animals had higher death rates. Mountain goats, elk, deer, black bears, and cougars were all wiped out. Eventually, these larger animals moved back into the area. Without enough food, many elk starved in the winters after the eruption. By 2014, the mountain goat population had grown to 65. In 2015, there were 152. Mountain goats are important to the Cowlitz Tribe. They used to collect goat wool left on the mountain. The tribe helps watch over the goat population, which is still recovering naturally.

Human History of Mount St. Helens

Stories from Native American Tribes

Native American stories explain the eruptions of Mount St. Helens and other Cascade volcanoes. The most famous story is the Bridge of the Gods tale, told by the Klickitat people.

The story says that the chief of all gods and his two sons, Pahto and Wy'east, traveled down the Columbia River. They were looking for a place to live. They found a beautiful area called The Dalles. The sons argued over the land. So, their father shot two arrows from his bow. One went north, the other south. Pahto followed the north arrow, and Wy'east followed the south. The chief then built the Bridge of the Gods so his family could meet.

The two sons fell in love with a beautiful maiden named Loowit. She could not choose between them. The young chiefs fought over her, destroying villages and forests. The earth shook so hard that the huge bridge fell into the river. This created the Columbia River Gorge's cascades.

As punishment, the chief of the gods turned each lover into a great mountain where they fell. Wy'east, with his head held high, became Mount Hood. Pahto, with his head bowed, became Mount Adams. The beautiful Loowit became Mount St. Helens. The Klickitat people call it Louwala-Clough, meaning "smoking or fire mountain." The Sahaptin call it Loowit.

The mountain is also very important to the Cowlitz and Yakama tribes. They believe the area above the treeline is spiritually significant. The mountain, which they call "Lawetlat'la" (meaning "the smoker"), is central to their creation story, songs, and rituals. Because of its cultural importance, over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) of the mountain are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Other tribal names for the mountain include "nšh'ák'w" ("water coming out") from the Upper Chehalis. The Kiksht term is "aka akn" ("snow mountain").

European Explorers and Settlers

Royal Navy Commander George Vancouver and his crew were the first Europeans to see Mount St. Helens. They spotted it on May 19, 1792, while exploring the northern Pacific Ocean coast. Vancouver named the mountain after British diplomat Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens on October 20, 1792.

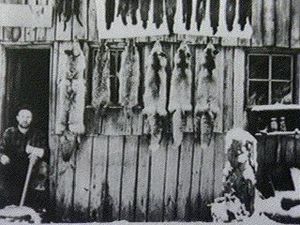

Years later, explorers and traders heard stories of an erupting volcano in the area. Geologists later figured out that an eruption happened in 1800. This marked the start of the 57-year-long Goat Rocks Eruptive Period. The Nespelem tribe of northeastern Washington was alarmed by the "dry snow" (ash). They supposedly danced and prayed instead of gathering food. They suffered from hunger that winter.

In late 1805 and early 1806, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition saw Mount St. Helens from the Columbia River. They did not report any ongoing eruption. However, they did report quicksand and clogged river conditions near Portland. This suggests an eruption by Mount Hood happened in the decades before.

In 1829, Hall J. Kelley tried to rename the Cascade Range the "President's Range." He also wanted to name each major Cascade mountain after a former U.S. President. In his plan, Mount St. Helens would have been called Mount Washington.

The first confirmed non-Native American eyewitness report of an eruption was in March 1835. It was made by Meredith Gairdner, who worked for the Hudson's Bay Company. He sent a report that was published in January 1836. In 1841, James Dwight Dana of Yale University saw the quiet peak from the Columbia River.

In late 1842, nearby European settlers saw what they called the "Great Eruption." This was a small eruption that created large ash clouds. Small explosions continued for 15 years. These eruptions were likely phreatic, meaning steam explosions. Josiah L. Parrish saw Mount St. Helens erupting on November 22, 1842. Ash from this eruption may have reached The Dalles, Oregon, 48 miles (77 km) southeast of the volcano.

British lieutenant Henry J. Warre sketched the eruption in 1845. Two years later, Canadian painter Paul Kane made watercolors of the gently smoking mountain. Warre's drawing showed material erupting from a vent about a third of the way down the mountain's west or northwest side. One of Kane's sketches also showed smoke from about the same spot.

On April 17, 1857, a newspaper reported that "Mount St. Helens, or some other mount to the southward, is seen ... to be in a state of eruption." This was the first reported volcanic activity since 1854. The lack of a thick ash layer suggests it was a small eruption.

Before the 1980 eruption, Spirit Lake was a popular spot for fun activities all year. In summer, people enjoyed boating, swimming, and camping. In winter, they went skiing.

Impact on People from the 1980 Eruption

Fifty-seven people died during the eruption. If the eruption had happened one day later, on a workday, more loggers would have been in the area. The death toll could have been much higher.

Eighty-three-year-old Harry R. Truman ran the Spirit Lake Lodge. He had lived near the mountain since 1929. He became famous in the media because he refused to leave before the eruption. His body was never found after the eruption.

Another victim was 30-year-old volcanologist David A. Johnston. He was stationed on nearby Coldwater Ridge. Moments before the pyroclastic flow hit his position, Johnston radioed his last words: "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" Johnston's body was never found.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter saw the damage. He said, "Someone said this area looked like a moonscape. But the moon looks more like a golf course compared to what's up there." A film crew was dropped by helicopter on St. Helens on May 23 to film the destruction. Their compasses spun in circles, and they quickly got lost. A second eruption happened on May 25. The crew survived and was rescued two days later by National Guard helicopter pilots. Their film, The Eruption of Mount St. Helens!, became a popular documentary.

The eruption also had negative effects far from the volcano. Ashfall caused about $100 million in damage to farms in Eastern Washington. This is equal to about $370 million today.

However, the eruption also had some good effects. Apple and wheat crops were larger in 1980. This might have been because the ash helped the soil hold moisture. The ash also became a source of income. It was used to make a fake gemstone called helenite. It was also used for ceramic glazes or sold as a souvenir to tourists.

Protecting the Mountain and Recent History

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan and the U.S. Congress created the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. This is a 110,000-acre (45,000 ha) area around the mountain. It is located within the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

After the 1980 eruption, the area was left to return to its natural state. In 1987, the U.S. Forest Service reopened the mountain for climbing. It stayed open until 2004, when new activity caused the area around the mountain to close. The Monitor Ridge trail, which allowed up to 100 hikers per day to climb to the top, stopped operating. On July 21, 2006, the mountain was opened to climbers again. In February 2010, a climber died after falling from the rim into the crater.

Because of the eruption, the state of Washington recognizes May as "Volcano Awareness Month." Events are held at Mount St. Helens and nearby areas. These events discuss the eruption, safety, and remember those who died.

On May 14, 2023, a mudslide and debris flow, called the 2023 South Coldwater Slide, destroyed the 85-foot (26 m) Spirit Lake Outlet Bridge. This bridge was on Washington State Route 504. The slide also cut off access to the Johnston Ridge Observatory. Closures and access to Coldwater Lake and hiking trails changed in the month after the slide.

Climbing and Fun Activities

Mount St. Helens is a popular climbing spot for both new and experienced mountaineers. People climb the peak all year, but it is most popular from late spring to early fall. All routes have steep, rough sections. Since 1987, climbers need a permit. A climbing permit is required all year for anyone going above 4,800 feet (1,500 m) on the mountain.

The usual hiking route in warmer months is the Monitor Ridge Route. It starts at the Climbers Bivouac. This is the most crowded route in summer. It gains about 4,600 feet (1,400 m) in about 5 miles (8.0 km) to reach the crater rim. It is hard work, but it is not a technical climb. Most climbers finish the round trip in 7 to 12 hours.

The Worm Flows Route is the usual winter route on Mount St. Helens. It is the most direct way to the top. This route gains about 5,700 feet (1,700 m) in elevation over about 6 miles (9.7 km) from the start to the summit. It does not require the technical climbing skills needed for other Cascade peaks like Mount Rainier. The route is named after the rocky lava flows around it. You can reach this route from the Marble Mountain Sno-Park.

The mountain is now circled by the Loowit Trail. This trail is at elevations of 4,000 to 4,900 feet (1,200 to 1,500 m). The northern part of the trail is a restricted zone. Camping, biking, pets, fires, and going off-trail are not allowed there.

On April 14, 2008, John Slemp, a snowmobiler, fell 1,500 feet (460 m) into the crater. A snow cornice (an overhanging mass of snow) broke beneath him. He was on a trip to the volcano with his son. Even after such a long fall, Slemp survived with only minor injuries. He was able to walk after stopping at the foot of the crater wall. A mountain rescue helicopter rescued him two days later.

A visitor center run by the Washington State Parks is in Silver Lake, Washington. It is about 30 miles (48 km) west of Mount St. Helens. It has a large model of the volcano, a seismograph, a theater program, and an outdoor nature trail.

Images for kids

-

Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, at 8:32 AM PDT.

See also

In Spanish: Monte Santa Helena para niños

In Spanish: Monte Santa Helena para niños