David A. Johnston facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

David Alexander Johnston

|

|

|---|---|

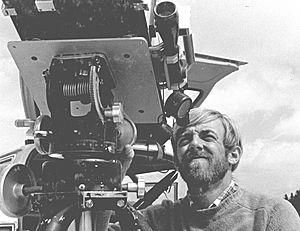

The last picture ever taken of Johnston, 13 hours before his death at the eruption site.

|

|

| Born |

David Alexander Johnston

December 18, 1949 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Died | May 18, 1980 (aged 30) Mount St. Helens, Washington, U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Killed by a pyroclastic flow caused by the volcanic eruption of Mount St. Helens |

| Education | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (BS) University of Washington (MS, PhD) |

| Occupation | Volcanologist |

David Alexander Johnston (December 18, 1949 – May 18, 1980) was an American volcanologist. He worked for the United States Geological Survey (USGS). David was killed by the powerful 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington state.

He was a main scientist on the USGS team watching the volcano. Johnston was at an observation post about 6 miles (10 km) away when the eruption happened. He was the first to report the eruption, shouting, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" before a fast-moving cloud of hot gas and ash swept him away. His body was never found, but parts of his trailer were found years later.

Johnston studied volcanoes all over the United States. He was known for carefully studying volcanic gases. These gases can help predict when a volcano might erupt. His hard work and positive attitude made him well-liked. After his death, many scientists praised him. Johnston believed scientists should take risks to help protect people from natural disasters. His work helped convince officials to close Mount St. Helens before it erupted. This decision saved thousands of lives.

David Johnston's Life and Career

David Johnston was born in Chicago, Illinois, on December 18, 1949. He grew up in Oak Lawn, Illinois, with his parents and one sister. His father was an engineer, and his mother was a newspaper editor. David often took photos and wrote for his school newspaper. He never married.

After high school, David went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He first planned to study journalism. But he found geology interesting and changed his major. His first geology project was studying old volcanoes in Michigan. This experience sparked his love for volcanoes. He worked hard and graduated with high honors in 1971.

After college, Johnston worked in Colorado studying two old volcanoes. This work led to his graduate studies at the University of Washington. He focused on reconstructing the eruption history of ancient volcanoes. His first experience with an active volcano was in Alaska in 1975. This was Augustine Volcano. When it erupted in 1976, he rushed back to study it. This became the focus of his Ph.D. work. He earned his Ph.D. in 1978.

In 1978, Johnston joined the United States Geological Survey (USGS). He monitored volcanic gases in the Cascade Range and Aleutian Islands. He helped develop the idea that changes in volcanic gases can help predict eruptions. His goal was to find a way to predict big volcanic blasts. He also visited Augustine Volcano every summer.

Johnston was based in California, but his work took him to many volcanoes. When earthquakes started shaking Mount St. Helens in March 1980, Johnston was nearby. He quickly became a leader in the USGS team. He was in charge of watching the volcanic gases.

Mount St. Helens Eruption

Early Warning Signs

Mount St. Helens had been quiet for 123 years. But in early 1980, things changed. On March 15, small earthquakes began shaking the area. For six days, over 100 earthquakes hit near the mountain. This showed that magma was moving underground.

By March 20, a magnitude 4.2 earthquake shook the area. Scientists then installed more seismic stations. By March 24, volcanologists like Johnston were sure an eruption was coming. Earthquakes increased greatly after March 25. On March 27, the volcano had a small eruption of steam and ash. This ash plume went nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 meters) into the air.

Over the next weeks, the volcano kept erupting steam and ash. Plumes sometimes reached 20,000 feet (6,100 meters). Many people came to watch the volcano. On April 17, scientists found a large bulge on the mountain's north side. This "cryptodome" meant magma was pushing up from inside. It suggested a dangerous side-blast could happen.

The Final Moments

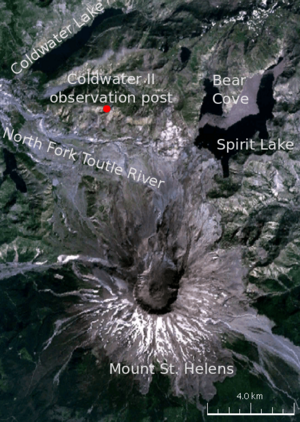

Johnston and other scientists set up observation posts. They used lasers to measure how the bulge was growing. Coldwater II, where Johnston was, was about 6 miles (10 km) north of the mountain. The bulge was growing 5 to 8 feet (1.5 to 2.4 meters) each day. Scientists also found high levels of sulfur dioxide gas. This showed pressure was building.

The volcano stopped its small eruptions on May 16 and 17. Cracks formed on the north side of the summit. This showed magma was moving.

At 8:32 a.m. on May 18, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake hit. This caused a huge landslide on the mountain's north face. The landslide removed the pressure on the magma. Mount St. Helens then exploded sideways. Hot, fast-moving clouds of gas and ash, called pyroclastic flows, rushed down the mountain. They moved at almost supersonic speeds.

Before the flows reached him, Johnston radioed his co-workers. He said: "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" Seconds later, his radio went silent. All contact was lost. Another person nearby, Gerry Martin, also reported seeing the blast hit Johnston's post. Martin then said, "It's going to hit me, too," before his radio also went silent.

The eruption was heard far away. But some survivors said the landslide and pyroclastic flows were silent as they raced down. This happens because of how air moves and changes temperature.

Johnston had famously told reporters that being on the mountain was like "standing next to a dynamite keg and the fuse is lit." He was one of the first scientists at the volcano. He helped lead the gas monitoring. He and other scientists kept people away from the volcano. They fought against pressure to reopen the area. Their work saved thousands of lives.

Search and Discovery

Graduate student Harry Glicken had been at the Coldwater II post for two and a half weeks. The night before the eruption, Johnston took his place. On May 17, Johnston went on patrol with another geologist, Carolyn Driedger. Johnston told her to go home, saying he would stay alone. Glicken took a famous photo of Johnston sitting by the trailer that evening. This was 13 and a half hours before the eruption.

After the eruption, rescue workers were sent out. The USGS pilot, Lon Stickney, flew over the area. He saw only bare rock and destroyed trees. He saw no sign of Johnston's trailer. Harry Glicken also tried to find Johnston. He convinced helicopter pilots to fly him over the devastated area. But the landscape had changed so much they could not find the post.

In 1993, workers building a road found pieces of Johnston's trailer. But his body was never found.

David Johnston's Legacy

Scientific Impact

Johnston is remembered by scientists and the government. He was known for being careful and dedicated. A USGS paper called him "an exemplary scientist." It also said he was "genuine, with an infectious curiosity and enthusiasm." An obituary said he was "among the leading young volcanologists in the world."

His death shocked his friends and co-workers. But most of them said Johnston died "doing what he wanted to do." His mother said, "Not many people get to do what they really want to do in this world, but our son did."

Since Johnston's death, predicting volcanic eruptions has gotten much better. Scientists can now predict eruptions days or months in advance. They use patterns in seismic waves to see magma movement. They also measure carbon dioxide gas and ground changes. This combination of methods has greatly improved predictions.

Johnston's story is now part of volcano history. He and Harry Glicken are the only two American volcanologists known to have died in a volcanic eruption. Glicken died in 1991 in Japan.

Memorials and Honors

Two trees were planted in Tel Aviv, Israel, to honor Johnston. A community center in his hometown was renamed the "Johnston Center."

On the second anniversary of the eruption, the USGS office in Vancouver was renamed the David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO). This observatory monitors Mount St. Helens. It helped predict all its eruptions between 1980 and 1985.

The University of Washington created a memorial fund in his name. It gives money to graduate students for research. This is called the 'David A. Johnston Memorial Fellowship for Research Excellence'.

An observatory was built where Coldwater II had been. It opened in 1997 and is called the Johnston Ridge Observatory (JRO). It is about 5 miles (8 km) from Mount St. Helens. The JRO lets people see the volcano's crater and the effects of the 1980 eruption. It cost $10.5 million to build. Thousands of tourists visit it each year. It has tours, a theater, and exhibits.

Johnston's name is on several public memorials. These include a granite monument at the Johnston Ridge Observatory. There is also a plaque at the Hoffstadt Bluffs Visitor Center.

In Films and Books

Johnston's story has been told in many documentaries and films.

In the 1981 TV movie St. Helens, actor David Huffman played a character based on Johnston. However, Johnston's parents felt the film did not show their son accurately. They said it made him seem like a daredevil, not a careful scientist. Many scientists who knew Johnston also protested the film.

Several documentaries have covered the eruption and Johnston's story. These include Up From the Ashes (1990) and episodes of Seconds From Disaster (2005) and Surviving Disaster (2006). His story was also featured in "Rescued From Mount St. Helens" (2017) on PBS.

Works

- "Guides to Some Volcanic Terranes in Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and Northern California". Circular. U.S. Geological Survey Circular. 838. United States Geological Survey. 1981. doi:10.3133/cir838. http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/WesternUSA/Circular838/framework.html.

- Johnston, David A. (1979). "Volcanic gas studies at Alaskan volcanoes". U. S. Geological Survey Circular (Reston, Virginia, US: United States Geological Survey) C 0804-B: B83–B84. ISSN 0364-6017.

- Johnston, David A. (1979). "Revision of the recent eruption history of Augustine Volcano; elimination of the "1902 eruption"". U. S. Geological Survey Circular (Reston, Virginia, US: United States Geological Survey) C 0804-B: B80–B84. ISSN 0364-6017.

- Johnston, David A. (1979). "Onset of volcanism at Augustine Volcano, lower Cook Inlet". U. S. Geological Survey Circular (Reston, Virginia, US: United States Geological Survey) C 0804-B: B78–B80. ISSN 0364-6017.

- Johnston, David A. (1978). Volatiles, magma mixing, and the mechanism of eruption of Augustine Volcano, Alaska. Ph.D. Thesis. Seattle, Washington, US: University of Washington.

- Johnston, David A. (1978). Volcanistic facies and implications for the eruptive history of the Cimarron Volcano, San Juan Mountains, SW Colorado. Master's Thesis. Seattle, Washington, US: University of Washington.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: David Alexander Johnston para niños

In Spanish: David Alexander Johnston para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |