Cascadia (independence movement) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cascadia

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag of Cascadia

|

|

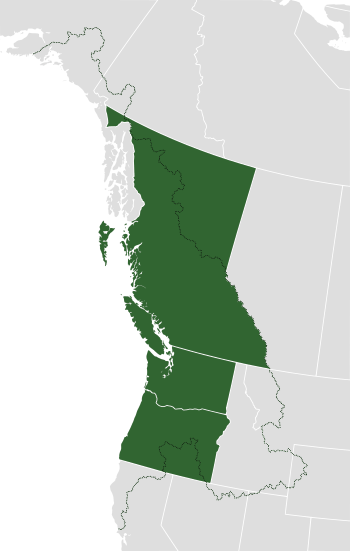

Boundaries of the bioregion with respect to current political divisions (Washington, Oregon and British Columbia).

|

|

| Largest city | Seattle |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) | Cascadian |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

1,384,588 km2 (534,592 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate

|

17,250,000 |

|

• 2010 census

|

15,105,870 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

|

• Total

|

US$1.1 trillion estimate |

|

• Per capita

|

$69,153 estimate |

|

a. *Statistics are compiled from US and Canadian census records by combining information from the states of Washington, Oregon and the province of British Columbia.

|

|

The Cascadia independence movement is a group of ideas and people who believe that a region in western North America, called the Cascadia bioregion, should be more connected, or even become its own country. A bioregion is an area defined by its natural environment, like rivers and mountains, rather than by political borders.

The proposed Cascadia region usually includes the Canadian province of British Columbia and the US states of Washington and Oregon. This area includes big cities like Seattle, Vancouver, and Portland. Some people imagine Cascadia stretching even further, from coastal Alaska in the north to Northern California in the south. It could also go inland to parts of Idaho, Montana, and other states.

If Cascadia were a country, based on the combined numbers for Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, it would have over 16 million people. Its economy would be very strong, producing more than US$675 billion worth of goods and services each year. With a land area of over 1.3 million square kilometers (534,572 sq mi), Cascadia would be one of the largest countries in the world. Its population would be similar to countries like Ecuador or the Netherlands.

Contents

What is the Cascadia Movement?

The Cascadia movement is made up of different groups with various goals. Some groups want the Cascadia bioregion to become fully independent. Others aim to create a strong network of communities that work together, offering an alternative to how countries are currently organized.

People in the Cascadia movement have several reasons for wanting closer ties or independence for the Pacific Northwest. These include protecting the environment, promoting local economies, and supporting personal freedoms. They also want to strengthen the unique regional identity of the area.

Alexander Baretich, who designed the Cascadia flag, believes the movement is not just about breaking away. He sees it as a way for the region to thrive and adapt to big challenges like climate change and other environmental issues.

Cascadia's Early History

Before the 1800s, over 500,000 Indigenous people lived in the Cascadia region. They belonged to many nations, like the Chinook, Haida, and Tlingit. These groups lived and traded along the natural river systems, using the waterways for travel and commerce. They spoke many different languages.

Today, many Cascadia and First Nation organizers believe it's important to respect Indigenous rights and self-determination. They argue that Indigenous groups should have the power to make their own decisions about their lands and cultures.

The 1800s: Early Ideas of Independence

Oregon Country and Columbia District

In 1813, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter about Fort Astoria, an early fur trading post. He saw it as the beginning of a "great, free, and independent empire" in the western part of the continent. He believed that freedom and self-government would spread from both the east and west, covering the whole continent.

Other important figures like John Quincy Adams also saw the Northwest as a potential "empire of Astoria." Even in the 1820s, some leaders thought the region west of the Rocky Mountains might become an independent nation.

Some early settlers in the 1840s also wanted to form their own country. John McLoughlin, a leader for the Hudson's Bay Company, argued for the independence of the Oregon Country. In 1843, settlers held meetings and many voted to create an independent republic. However, this idea was put on hold.

Later, the settlers formed a Provisional Government. A leader named Osborne Russell suggested that the Oregon Territory should not join the United States. Instead, he wanted it to become a "Pacific Republic" stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Continental Divide.

American Civil War and Regional Identity

When the Southern states left the U.S. to form the Confederacy, some settlers in the Oregon Territory saw another chance for independence. However, this movement did not gain enough support.

Even though independence movements didn't succeed, people in the Pacific Northwest began to think about their own unique culture. In 1894, Adella M. Parker, a leader at the University of Washington, said that the West should create its own ideals and not just follow the East. She believed something "wild and free" would come from the West.

The 1900s: New Ideas and Movements

The State of Jefferson

In the 1940s, a well-known movement tried to create a "State of Jefferson." This idea involved Southern Oregon and Northern California breaking away from their states to form a new state within the U.S. People in these areas felt their state governments weren't paying enough attention to them.

Organizers even blocked a highway and collected tolls to draw attention to their cause. Their flag had a gold pan and two X's, symbolizing a "double cross" by their state governments. However, the movement quickly ended after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, as the country focused on World War II.

Ecotopia: A Vision of a Green Future

In 1975, Ernest Callenbach wrote a famous book called Ecotopia. This novel imagined a secret republic made up of Washington, Oregon, and Northern California. In the story, this region had left the U.S. 20 years earlier. The book describes a society that has been carefully planned to live in a way that protects the environment and is sustainable.

Cascadia and Bioregionalism

The idea of Cascadia is strongly linked to bioregionalism. This is the belief that political boundaries should match natural areas, like river systems, rather than artificial lines drawn on a map. Cascadians feel that the Cascadia bioregion better represents the people and environment than current state or national borders.

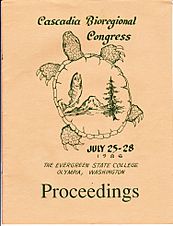

Bioregional Congresses

The early Cascadia movement grew from meetings called "Bioregional Congresses" in the 1980s. These gatherings brought people together to discuss social needs and how to govern their region based on natural boundaries. The first Cascadia Bioregional Congress was held in 1986 in Olympia, Washington.

The Cascadia Bioregion

The Cascadia bioregion is defined by the watersheds of major rivers like the Fraser, Snake, and Columbia. It includes parts of many states and provinces, stretching from California in the south to Alaska and Alberta in the north.

Bioregionalists believe that culture comes from the place where people live. They use this idea to argue for more independence and self-rule for the Cascadia region. They see it as a way to create communities that are more connected to their environment.

The Cascadian Bioregional Flag

The Cascadian Bioregional Flag, often called the Doug Flag, is a key symbol for the movement. It was designed in 1994 by Alexander Baretich. The flag's colors represent the region's natural features:

- Green for the forests.

- Blue for the waters and the Pacific Ocean.

- White for the snow-capped mountains.

A Douglas Fir tree in the middle symbolizes the strength and endurance of the region.

Alexander Baretich says the flag is not about war or national glory. Instead, it shows a love for the bioregion, its natural boundaries, and the place where people live. Anyone who is part of the Cascadia movement can use the flag for non-commercial purposes with his permission.

Many leaders and groups have embraced the idea of Cascadia as a connected economic region. For example, former mayor of Seattle Paul Schell created the "Main Street Cascadia" idea in the 1990s. He believed that Cascadia better represented the cultural and natural reality of the area from Eugene, Oregon, to Vancouver, British Columbia.

The region has several groups that work together across borders. Since 2008, the Pacific Coast Collaborative has helped coordinate policies on environmental protection, forestry, and transportation.

The area from Vancouver, B.C., to Portland, Oregon, is seen as a growing "megaregion." This means that the boundaries between big cities are blurring, creating a larger connected area. These megaregions have linked economies, shared natural resources, and common transportation systems. This specific area holds over 80% of Cascadia's population. Programs like the enhanced driver's license make it easier for people to cross the border between Washington and British Columbia.

Modern Secessionist Ideas

Some Cascadia independence groups believe that the governments in the eastern parts of the U.S. and Canada are too far away and don't understand the region's needs. They argue that these distant governments slow down efforts to connect the bioregion more closely. These ideas of regional independence have roots going back to the Oregon Territory.

After the 2004 U.S. presidential election, some people in Washington and Oregon felt a renewed interest in separating from the U.S. This was because these states often vote differently from the rest of the country.

In 2016, after Donald Trump was elected U.S. president, there was a new surge in interest for Cascadian independence. Some groups even proposed a vote on secession in Oregon, though this proposal was later withdrawn. New Cascadia organizations have also formed during this time.

People in the Cascadia movement celebrate May 18 as "Cascadia Day." This date marks the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, a famous volcano in the region. The week around this date is called "Cascadia Culture Week."

In British Columbia, the Cascadia Party formed in 2016 to support the idea of independence for the Cascadia bioregion. In 2021, the Cascadia Bioregional Party was also created, advocating for independence from both the United States and Canada.

Public Support for Independence

Canada

Recent polls in British Columbia show growing support for the province to become an independent country, or to join with Washington and Oregon. A 2020 poll found that 27% of British Columbians supported independence, up from 17% in previous years. Younger people (aged 18-34) were more likely to support this idea, with 37% in favor.

Support for joining with Washington and Oregon was even higher, especially among younger generations. About 66% of those aged 18-34 supported this idea, along with 60% of those aged 35-54.

Another study in 2017-2018 found that 54% of British Columbians felt they had the most in common with Washington state. This connection has continued to grow over the years.

United States

While there isn't specific research on support for Cascadia independence in Washington and Oregon, the idea of states leaving the U.S. is at a high point. A 2021 study found that 47% of Democrats in the Pacific region (Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Hawaii, California) supported the idea of their state leaving to join a new regional union. Overall, 37% of Americans supported the idea of secession.

Another poll in 2022 found that 52% of Trump voters and 41% of Biden voters agreed that it might be time to divide the country into different unions. Earlier, in 2018, a national poll showed that 39% of Americans supported the idea of independence, and 68% were open to a state or region peacefully leaving the United States.

Even though these studies don't specifically mention Cascadia, they show a general openness to new political arrangements. In 2011, Time magazine listed Cascadia as one of the "Top 10 Aspiring Nations," though they noted it had little chance of becoming real.

Cascadia in Popular Culture

- The Doug flag is widely used by supporters of the Cascadia movement. It is also adopted by sports teams in the region, like the Portland Timbers soccer club. The three major soccer teams in the region compete for the Cascadia Cup.

- The documentary Occupied Cascadia explores bioregionalism and environmentalism in the region.

- In 2010, artist Lloyd Vivola wrote a song called "O Cascadia – A Folk Anthem for the Pacific Northwest." An orchestral version of this song was later adopted by the Cascadia National Team.

- The Cascadia Association Football Federation (CAFF) was founded in 2013. They send a soccer team to compete in international tournaments for regions not recognized by FIFA. In 2018, they sent a team to the ConIFA World Football Cup in London.

- The 2016 book Towards Cascadia looks at the identity of the Pacific Northwest and the possibility of Cascadia becoming independent.

- In 2019, the band Said the Whale released an album called "Cascadia."

- The 2020 video game Project Wingman features a fictional war where "United Cascadia" (including Alaska and parts of the West Coast) tries to break away from a larger superpower.

Images for kids

-

The Oregon Country as claimed by the United States. The Columbia District extended much farther north.

See also

In Spanish: Cascadia para niños

In Spanish: Cascadia para niños