Walther Rathenau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Walther Rathenau

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Foreign Minister of Germany | |

| In office 1 February – 24 June 1922 |

|

| President | Friedrich Ebert |

| Chancellor | Joseph Wirth |

| Preceded by | Joseph Wirth (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Wirth (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 September 1867 Berlin, North German Confederation |

| Died | 24 June 1922 (aged 54) Berlin, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | German Democratic Party |

| Relations | Emil Rathenau (father) |

| Profession | Industrialist, politician, writer |

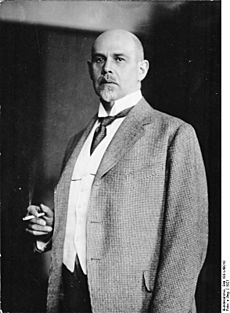

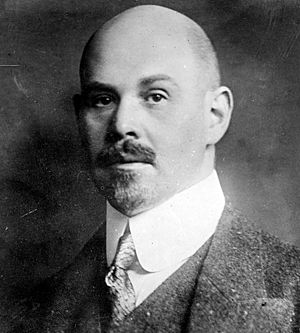

Walther Rathenau (born September 29, 1867 – died June 24, 1922) was an important German businessman, writer, and politician. He served as the Foreign Minister of Germany from February to June 1922.

Rathenau was the son of Emil Rathenau, a well-known Jewish businessman. His father founded the electrical company Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG). Walther earned a special degree in physics from the University of Berlin. He then worked in various industries before joining the AEG board. He became a top industrialist in Germany. In 1915, he became the head of AEG after his father passed away. During World War I, he helped organize Germany's war efforts. He led the War Raw Materials Department.

After the war, Rathenau helped start the German Democratic Party. He was a key person in the new Weimar Republic government. In 1921, he became the minister of reconstruction. A year later, he was made foreign minister. Rathenau helped create the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo. This agreement improved relations and trade between Germany and Soviet Russia. Some right-wing groups, including the early Nazi Party, did not like this treaty. They also disliked Rathenau's belief that Germany should follow the Treaty of Versailles. They falsely called him part of a "Jewish-Communist conspiracy."

Two months after the treaty was signed, Rathenau was killed by an extreme nationalist group called Organisation Consul in Berlin. His death made many Germans sad. People protested against political violence. This briefly made the Weimar Republic stronger. Rathenau became known as a hero for democracy. After the Nazis took power in 1933, they banned all ways of remembering Rathenau.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Walther Rathenau was born in Berlin. His father, Emil Rathenau, was a leading Jewish businessman. Emil founded the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), an electrical company. Walther's mother was Mathilde Nachmann.

He studied physics, chemistry, and philosophy in Berlin and Strasbourg. He earned his doctorate in physics in 1889. Being Jewish and wealthy made him a controversial figure in German politics. This was a time when anti-Jewish feelings were growing.

Rathenau shared his feelings about growing up Jewish in Germany. He said his loyalty to Germany was the same as any other German:

I am a German of Jewish origin. My people are the German people, my home is Germany, my faith is German faith, which stands above all denominations.

He worked as an engineer in a Swiss factory. Then he managed a small company in Bitterfeld. There, he experimented with electrolysis, a way to use electricity to separate chemicals. In 1899, he returned to Berlin and joined the AEG board. He became a very successful industrialist. He set up power stations in cities like Manchester, Buenos Aires, and Baku. AEG also bought a streetcar company in Madrid. He was involved with 84 companies around the world. AEG was known for its smart business methods. Rathenau was good at improving companies. His skills made AEG very rich.

Helping Germany in World War I

Rathenau was also a journalist. He wrote an article in the Berliner Tageblatt. In it, he accused his own country of secretly influencing politics. During World War I, his views became stronger. He held important positions in the War Ministry's Raw Materials Department. He became chairman of AEG in 1915 after his father died.

Rathenau was key in setting up the War Raw Materials Department (Kriegsrohstoffabteilung, KRA). He led it from August 1914 to March 1915. This department focused on raw materials that were hard to get because of the British blockade. It also managed supplies from occupied areas. The KRA set prices and controlled how materials were given to war industries. It also worked on finding new materials to replace old ones.

His Character and Ideas

Rathenau wrote about how people and society should be responsible to each other. He believed in courage, vision, and creativity. He also thought technology should help workers. He felt that work should bring "pleasure from profit" to improve society.

Some people criticized him, suggesting that Jewish people could not put Germany first. This idea, that Jews were "our misfortune," led to many anti-Jewish political groups forming in the 1880s. At that time, there were no Jewish officers in the Prussian Army. The ruling class was often anti-Jewish.

After the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Rathenau started a "League for Industry." He believed Germany's defeat was due to a lack of industrial readiness. He wanted to clear Germany of blame for the war.

A Statesman After the War

Rathenau was a moderate politician. After World War I, he helped found the German Democratic Party. He cared deeply about social equality. He did not want the government to own all industries. Instead, he wanted workers to have more say in how companies were run. His ideas were important for the new government.

He was suggested as a candidate for the first President of Germany. But when he spoke in the Reichstag (German parliament), he was laughed at. This upset him. Germany was very divided after the war. Rathenau believed that a small town was not the right place for the capital.

In 1918, he created the ZAG. This group aimed to build a collective economic community. Rathenau supported free trade. He believed in being prepared and efficient. His ideas influenced many, including his colleague Wichard von Moellendorff.

Rathenau became Minister of Reconstruction. In 1921, he met with British and French leaders to discuss war payments. He built good relationships with them. He was confident that Germany could meet its obligations. He also warned against the problems of other countries.

In 1922, he became Foreign Minister. He knew his life might be in danger. He insisted that Germany should fulfill its duties under the Treaty of Versailles. But he also wanted to change some of its terms. This made extreme German nationalists very angry. He also angered them by negotiating the Treaty of Rapallo with the Soviet Union. This treaty was signed on April 16, 1922. It secretly allowed Germany to rearm, including making German airplanes in Russia.

Leaders of the (then small) National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazis) and other extreme groups falsely claimed he was part of a "Jewish-Communist conspiracy." This was untrue, as Rathenau was a German nationalist who had helped his country during the war. A British politician, Robert Boothby, described him as a unique person: "He was something that only a German Jew could simultaneously be: a prophet, a philosopher, a mystic, a writer, a statesman, an industrial magnate of the highest and greatest order, and the pioneer of what has become known as 'industrial rationalization'."

Even though he wanted Germany and the Soviet Union to work together, Rathenau was careful about Soviet methods:

We cannot use Russia's methods, as they only and at best prove that the economy of an agrarian nation can be leveled to the ground; Russia's thoughts are not our thoughts. They are, as it is in the spirit of the Russian city intelligentsia, unphilosophical, and highly dialectic; they are passionate logic based on unverified suppositions. They assume that a single good, the destruction of the capitalist class, weighs more than all other goods, and that poverty, dictatorship, terror and the fall of civilization must be accepted to secure this one good. Ten million people must die to free ten million people from the bourgeoisie is regarded as a harsh but necessary consequence. The Russian idea is compulsory happiness, in the same sense and with the same logic as the compulsory introduction of Christianity and the Inquisition.

The issue of war reparations (payments Germany had to make) was a big problem for Rathenau. Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles demanded payments that would take Germany many decades to repay. Rathenau wanted to change the idea of war guilt into financial responsibility. He tried to convince Germans that they had to pay. He argued that other countries would then see that Germany could meet its duties.

Assassination and Its Impact

On June 24, 1922, two months after the Treaty of Rapallo was signed, Rathenau was killed. On that Saturday morning, Rathenau was being driven from his home in Berlin-Grunewald to the Foreign Office. During the drive, his car was passed by another car. In it were Ernst Werner Techow, Erwin Kern, and Hermann Fischer. Kern shot Rathenau with a submachine gun, killing him instantly. Fischer then threw a hand grenade into the car. Techow quickly drove them away. Others involved in the plot included Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon. All the attackers were part of the ultra-nationalist secret group called Organisation Consul (O.C.). A memorial stone in Berlin marks the spot where he was killed.

Rathenau's murder was one of many attacks by Organisation Consul. They had also killed former finance minister Matthias Erzberger in 1921. The leader of Organisation Consul, Hermann Ehrhardt, ordered the murders. Ehrhardt and his men hoped Rathenau's death would cause the government to fall. They wanted a civil war, believing their group would then be asked to help. After winning, Ehrhardt hoped to create a strong, authoritarian government.

However, the terrorists' goals were not met. There was no civil war. Instead, millions of Germans gathered to show their sadness and protest against the violence. When the news reached the Reichstag, there was chaos. Chancellor Joseph Wirth gave a famous speech. He pointed to the right side of the parliament and said, "There is the enemy – and there is no doubt about it: This enemy is on the right!"

The crime was quickly solved. Willi Günther bragged about his part and confessed. Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst Werner Techow were arrested soon after. Fischer and Kern were found at Saaleck Castle. Kern was killed by a police bullet, and Fischer then took his own life.

When the case went to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was charged with murder. Other people were charged with various crimes, including Ernst von Salomon. The prosecution focused on the anti-Jewish hatred behind the plot. Rathenau had often been attacked with anti-Jewish insults. The killers were members of an anti-Jewish group. Kern had falsely claimed Rathenau was part of a "Jewish-Communist conspiracy." But the defendants denied they killed him because he was Jewish. The court could not fully prove Organisation Consul's involvement. Techow received fifteen years in prison.

At first, Rathenau's death made the Weimar Republic stronger. A law was passed to protect the Republic. June 24 became a day of public remembrance. Rathenau's death was seen as a sacrifice for democracy.

This changed when the Nazis took power in 1933. The Nazis removed all public memorials to Rathenau. They closed the museum in his home and renamed streets and schools. Instead, they honored his killers.

The Nuremberg U-Bahn station Rathenauplatz is named after him and features his portrait.

In Books and TV

Walther Rathenau is thought to be partly the inspiration for a character named Paul Arnheim in Robert Musil's novel The Man Without Qualities. He also appears as a ghost in Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow. In 2017, the story of his assassination was shown in the first episode of the National Geographic series Genius.

His Writings

- Reflektionen (1908)

- Zur Kritik der Zeit (1912)

- Zur Mechanik des Geistes (1913)

- Von kommenden Dingen (1917)

- Vom Aktienwesen. Eine geschäftliche Betrachtung (1917)

- An Deutschlands Jugend (1918)

- Die neue Gesellschaft (1919) The New Society translated by Arthur Windham, (1921) New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- Der neue Staat (1919)

- Der Kaiser (1919)

- Kritik der dreifachen Revolution (1919)

- Was wird werden (1920, a utopian novel)

- Gesammelte Schriften (6 volumes)

- Gesammelte Reden (1924)

- Briefe (1926, 2 volumes)

- Neue Briefe (1927)

- Politische Briefe (1929)

See Also

In Spanish: Walther Rathenau para niños

In Spanish: Walther Rathenau para niños

- Contributions to liberal theory

- 1920s Berlin

- Liberalism

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |