Washington–Franklin Issues facts for kids

The Washington–Franklin Issues are a special set of stamps from the United States. They show pictures of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. The U.S. Post Office released these stamps between 1908 and 1922.

What makes these stamps unique is that they only use two main pictures. These are the faces of Washington and Franklin, shown from the side. Every stamp in this series, no matter its value, uses one of these two pictures. This was different from older stamps, which showed many different famous Americans. But it also brought back an old tradition. Washington and Franklin were on the very first American stamps in 1847!

Early Washington–Franklin stamps (from 1908 to 1911) had olive branches around the faces. After 1912, stamps with Franklin's picture started to have oak leaves instead. Olive branches often mean peace, and oak leaves can mean strength. But the Post Office didn't say why they chose these designs.

These stamps came in many values, from 1 cent up to 5 dollars. Each value was printed in a different color. There were five main designs used to print over 250 different stamps over 14 years! The stamps were made by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington D.C. They mostly used a method called flat-plate printing. But they also tried new ways, like the rotary printing press and offset printing.

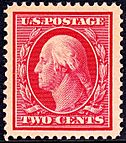

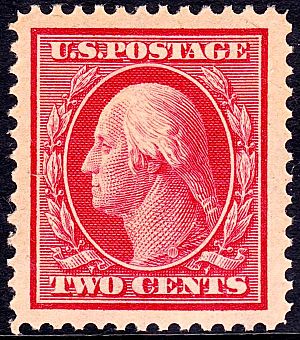

The very first Washington–Franklin stamp was a 2-cent stamp. It came out on November 16, 1908. More stamps followed, even during World War I. The last one was issued in 1923. This series lasted for almost 15 years, which was longer than any other U.S. stamp series made by one printer.

Contents

Why New Stamps Were Needed

Before the Washington–Franklin stamps, making U.S. stamps was still improving. People often complained to the Post Office about their stamps.

For example, in 1869, the Post Office released stamps that didn't just show presidents. People didn't like this change. They also complained that the stamps were too small or had bad glue. So, those stamps didn't last long.

Over the years, other complaints came in. People didn't like the stamp designs or had trouble tearing them apart. Some even said the glue tasted bad! Postal workers also complained. They said many stamps had similar colors, making it hard to sort mail quickly.

Around 1900, improving stamps became a big topic. Even President Theodore Roosevelt got involved. He wanted Abraham Lincoln on the new 1908 stamps for Lincoln's 100th birthday. But Lincoln wasn't included in this series. Instead, he got his own special stamp in 1909. Many of the new ideas used for the Washington–Franklin stamps came from trying to fix these old problems.

How the Stamps Looked

The Washington–Franklin stamps had a simple, classic look. They showed either George Washington or Benjamin Franklin from the side. Early stamps had olive branches around their pictures.

This was a big change from the stamps made in 1902–03. Those stamps showed many different American figures. But they had very fancy designs around them. Some people thought these designs were too flashy. They felt the fancy borders took away from the main picture. So, the Washington–Franklin stamps were made with a much simpler design.

Originally, the idea was to have only Washington on all the stamps. This idea came from Charles H. Dalton. He admired British stamps, which all showed the same picture of King Edward VII. Dalton thought U.S. stamps should do the same with Washington.

However, there was a long tradition of putting Franklin on every 1-cent stamp since 1851. So, Franklin was included on the 1-cent stamp in the 1908 series. The famous artist Clair Aubrey Houston designed the Washington–Franklin series. He designed many stamps.

Most of the 1902–03 stamps had the same colors as older stamps. But for the Washington–Franklin set, new and different colors were chosen for stamps 6-cents and higher.

Even though there were over 250 different Washington–Franklin stamps, they only used five basic designs. Two main pictures, one of Washington and one of Franklin, were used in these five designs. The picture of Washington was based on a sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon. The picture of Franklin was based on a sculpture by Jacques Caffieri.

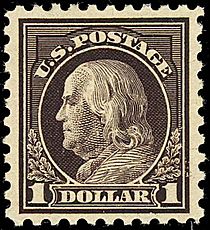

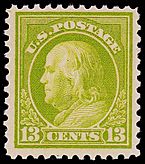

As the series continued, Washington and Franklin sometimes swapped places on stamps of the same value. This was the first time in U.S. stamp history that two different people appeared on the same stamp value in one series. Both Washington and Franklin eventually appeared on the 1-cent, 8-cent, 10-cent, 13-cent, 15-cent, 50-cent, and 1-dollar stamps.

At first glance, the design types may appear almost the same.

- Washington with Olive branches, postage spelled out, TWO CENTS.

- Franklin with Olive branches, the value spelled out, ONE CENT. (Only 1- and 2-cent stamps from 1908, 1909, and 1910 had the value spelled out.)

- Washington with Olive branches, value in numbers. Used on most stamps except 9, 11, 12, 20, 30-cent, and 2, 5-dollar stamps.

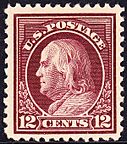

- Franklin with Oak leaves, value in numbers. Used on stamps from 8-cents to 1-dollar.

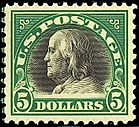

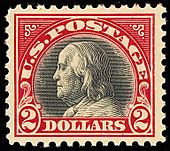

- Franklin with a horizontal frame. Used on 2 and 5-dollar stamps, value in numbers.

For the first four designs, printing plates needed two steps. One part of the plate had the Washington or Franklin picture. The other part had the frame and letters. After both parts were pressed onto the steel plate, it was heated to get it ready for printing.

Lower value stamps had 400 pictures on one printing plate, called a flat plate. The 1-dollar stamp used a flat plate with 200 pictures. The fifth design (for $2 and $5 stamps) needed different plates for each part. The frame was printed first in color. Then, the Franklin picture was printed over it in black. These $2 and $5 stamps used plates with 100 pictures.

Different Stamp Series

The first Washington–Franklin stamp was a 2-cent red Washington stamp. It came out on November 16, 1908. It was used to mail a standard letter. Seven different series of Washington–Franklin stamps were released over time. They had values from 1-cent up to 1 or 5 dollars, depending on the series.

You can tell the different series apart by a few things:

- The size of the perforations (the little holes that help you tear stamps apart).

- The type of paper used.

- Sometimes, the printing method.

Four or five basic paper types were used. Two had watermarks (hidden designs in the paper). One paper type had no watermark. In 1909, a rare bluish paper was used. It had 35% rag material mixed with wood pulp. You can see its faint bluish-gray color.

1908–09 Series

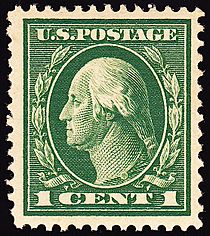

The first Washington–Franklin stamps came out in December 1908. They showed Washington and Franklin with olive branches. On the 1-cent and 2-cent stamps, the value was written out as ONE CENT or TWO CENTS. On other stamps (3-cents to 1-dollar), the value was in numbers. Franklin only appeared on the 1-cent stamp in this series. Washington was on stamps from 2-cents to 1-dollar.

The Post Office didn't make 2-dollar or 5-dollar stamps in this series. They still had plenty of those values from the 1902–03 series.

These first stamps had perforations of size 12. They were printed on paper with a double-line watermark. This watermark had large letters saying USPS hidden in the paper. These large letters sometimes made the stamp sheets weak. Stamps would tear apart easily before customers even got them. So, the double-line watermark was stopped in 1910. A single-line watermark with smaller letters replaced it.

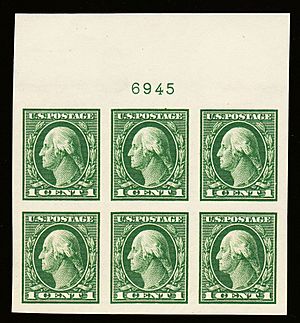

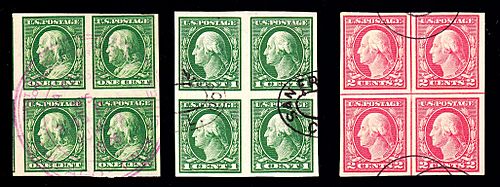

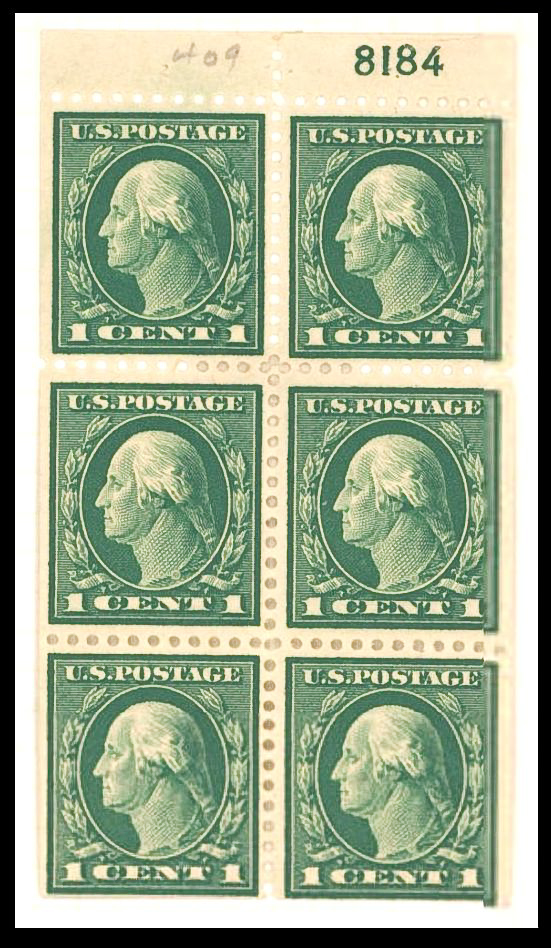

Because 1-cent and 2-cent stamps were very popular, they were also printed in small  . Each booklet page had six stamps.

. Each booklet page had six stamps.

The paper used for these stamps was dampened before printing. This helped the ink soak in better. But when the paper dried, it shrank. This made the rows of stamps closer together. It was hard to line up the perforations correctly. Many sheets had off-center perforations. About 20% of the sheets were so off-center they had to be destroyed. Finding well-centered stamps from this early series is hard. They are worth much more to collectors.

- The ONE CENT and TWO CENTS designs appear in the 1909 and 1910–11 series.

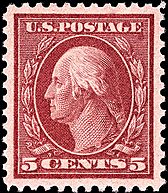

- The 3c, 4c, 5c and 6c designs appear in every series except that of 1912–1914.

- The 7c Washington-head (shown below) doesn't appear until 1914.

- The 8c, 10c and 15c Washington-heads also appear in the 1909 and 1910–11 series.

- The 13c Washington-head also appears in the 1909 series.

- The 50c and 1-dollar Washington-heads are exclusive to the 1908 series and appear nowhere else in the Issue.

- There are no Washington-heads with denominations of 9c, 11c, 12c, 20c 30c, $2 and $5.

1909 Series: Bluish Paper

In 1909, the Post Office tried a new paper to stop shrinkage. They printed stamps on bluish-paper. This paper had 35% rag material. If you compare it to regular paper, you can see the bluish tint on the back. This paper helped a little with shrinkage but didn't solve the problem completely. So, they stopped using it.

These stamps also had size 12 perforations. Stamps on bluish paper ranged from 1c to 15c. They were only sold in Washington D.C. So, used stamps often have a Washington D.C. postmark. Most stamps from this series are rare and expensive. The 1-cent and 2-cent stamps are more affordable. About 3 million of each were printed. Other values were printed in very small numbers and are very valuable. The 4-cent and 8-cent stamps are the rarest. They were never even released for postal use. They reached the public later when the Post Office traded them to stamp dealers.

1910–11 Series

For the 1910–11 series, the Post Office stopped using special paper. Instead, they tried two other things to fix paper shrinkage. First, they spaced the stamp pictures on the outer edges of the printing plate wider apart. Second, they stopped using the complicated double-line watermark. They thought it might cause uneven shrinkage. They replaced it with a simpler single-line watermark.

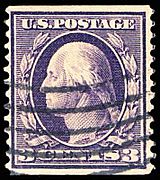

This series was also perforated 12. It used the same Franklin and Washington designs. However, it didn't include all the values from earlier series. The 13c Washington stamp, and the 50c and $1 Washington stamps from 1908–09, were left out. These three designs never appeared again in later Washington–Franklin series.

1912–1914 Series

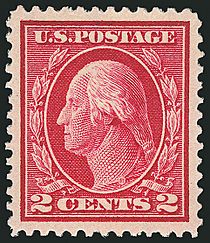

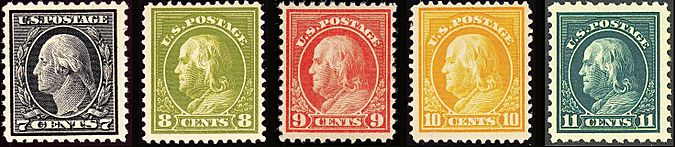

By 1912, postmasters complained that too many similar Washington stamps confused postal clerks. Clerks sometimes gave customers higher value stamps by mistake. To fix this, the Post Office made a big change in the 1912–1914 series. Washington would only appear on lower value stamps. All stamps 8c and higher would show Franklin. This made it easier to tell cheap stamps from expensive ones.

To make the difference even clearer, the Post Office added an oak-leaf frame for the Franklin stamps. This removed olive branches from the higher values and from Washington.

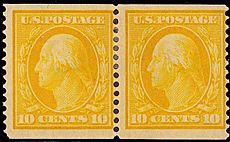

So, in early 1912, a new 1-cent stamp came out with Washington's picture. Franklin had been on all 1-cent green stamps before this. This was the first U.S. stamp sold in booklet form before full sheets were available. The 1-cent and 2-cent stamps now showed their values in numbers instead of words. The new Franklin oak leaf design came out in January with a 10-cent yellow stamp. Other high values soon followed. In this series, 7, 9, 12, 20, and 30-cent stamps appeared for the first time in the Washington–Franklin issues.

This series also had perforations of size 12. Stamps between 1¢ and 50¢ were printed on single-line watermarked paper. But the 50¢ and $1 stamps used double-line watermarked paper left over from the 1908 series. The 3, 4, 5, and 6-cent stamps were not printed in this series because there were still enough of them.

A special stamp was the 7-cent Washington-head in black. It came out on April 29, 1914. About 5 million were printed, which is a low number for a regular stamp. It was only available for five months.

The 50-cent and 1-dollar Franklin stamps first appeared on February 12, 1912. These stamps were printed from plates with 200 pictures. Smaller value stamps used plates with 400 pictures. Since there was old double-line watermarked paper from 1908 for 200-picture plates, it was used for these two stamps. When that paper ran out, new single-line watermarked paper was cut to the right size. So, the 50-cent Franklin stamp can be found on two paper types in this series. The 1-dollar Franklin was not printed again until 1916. The 50-cent and 1-dollar Franklin and Oak leaves stamps appeared again in the next three series.

1914–15 Series

This series continued to have Washington on 1-cent through 7-cent stamps. Franklin was on 8-cent through 1-dollar stamps. It was the first series to include the 11-cent stamp with the Franklin and Oak leaves design. This stamp was slate-green and appeared again in the 1916 and 1917 series.

Lower value stamps were printed from 400-picture plates on single-line watermarked paper. The 1-dollar Franklin was printed from 200-picture plates using double-line watermarked paper.

Because of problems with stamps tearing easily with size 12 perforations, this series used size 10 perforations. However, this coarser size also caused problems. It made stamps harder to separate, often leading to torn stamps.

1916–17 Series

The 1916–17 series stopped using watermarked paper. By this time, the old 2-dollar and 5-dollar stamps had run out. Instead of making new Franklin designs for these values, the Post Office just reprinted the 2-dollar and 5-dollar stamps from 1903. These showed James Madison and John Marshall. So, some people argue these two stamps don't truly belong to the Washington–Franklin Issues.

Unlike earlier series, this one didn't add or remove any values. It had all the same values (1-cent to 1-dollar) and colors as the 1914–15 series. It also kept the size 10 perforations.

There was a long-standing belief that the 30¢ stamp was left out of this series. No Post Office records showed it was issued. But later, some copies of a 30¢ stamp that seemed unwatermarked were found. In 1957, it was given a special number in the Scott catalogue. However, in 2008, a stamp-rating service found a "ghost" watermark on one of these stamps. This brought up the question of whether the unwatermarked version was ever truly issued. If it exists, the 30¢ unwatermarked perforated 10 stamp from 1916–17 is very rare. Fewer than 300 copies have been confirmed.

1917–1920 Series

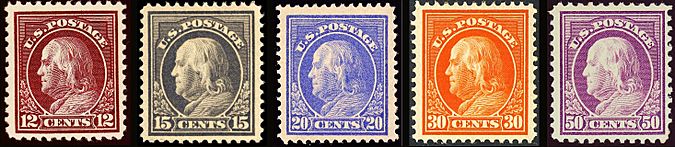

The 1917–1920 series had perforations of size 11. It included all the values from the two previous series. But it also added three new Franklin stamps: 13-cents, 2-dollars, and 5-dollars. The 2-dollar and 5-dollar stamps came out later in this series. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing was busy replacing old printing plates and trying new things.

These two higher value stamps were printed in two colors. The Franklin picture was in black, and the frame was in color. They were also different because they were wider than they were tall (landscape format), unlike the usual taller (portrait) stamps. Collectors often call the 2-dollar and 5-dollar Franklin-head stamps the 'Big Bens'.

The 2-dollar Franklin was supposed to be carmine-red and black. But some of the printing ink turned out orange. This kind of color difference can happen in stamp making. But this time, it was a completely different color. By the time officials noticed, many sheets had already been sent out. In 1920, a second printing of the 2-dollar Franklin was made. This time, it was the correct carmine-red and black. These were used for 3 to 4 years. So, there are about 15 red and black stamps for every 1 orange and black stamp.

The 1-cent to 1-dollar stamps were printed on plates with 400 pictures. They were cut into sheets of 100 stamps for sale. But the 2-dollar and 5-dollar stamps were printed on plates with 100 pictures. They didn't need to be cut and were sold as full sheets. This means there are no 2-dollar or 5-dollar stamps with a straight edge (an edge that hasn't been perforated). All the lower value stamps can be found with straight edges.

Offset Printing Method

During World War I, some ingredients for stamp ink came from Germany. When these became unavailable, the new materials used had gritty bits. This caused the stamp printing plates to wear out much faster. To fix this, the U.S. Post Office started using a new method called offset printing for some Washington-head stamps.

Offset printing involves taking a photo of the stamp design. This image is then transferred to a glass plate, which becomes the printing plate. Setting up this process took more time than engraving. But once the photo plate was made, it only took about an hour to replace a worn-out printing plate.

Stamps made by offset printing look a bit different. They have a smoother surface. Engraved stamps have lines that are slightly raised. Offset stamps often have a softer or grayish color. It's usually easy to tell them apart, especially when compared to an engraved stamp.

Three values were printed using offset printing: 1-cent, 2-cents, and 3-cents. There are different "types" of these stamps. These types have small differences in the lines on Washington's "toga rope" or other parts of the design. You usually need a magnifying glass to see these differences.

Offset stamps usually had perforations of size 11. One exception was a 1-cent stamp from 1919, which had size 12½ perforations. The first offset Washington–Franklin stamp was a 3-cent Washington-head, issued on March 22, 1918. The 1-cent green followed on December 24, 1918. The different types of the 2-cent stamp came out on March 15, 1920.

Starting in 1919, stamps without any perforations (called imperforate) were also issued. These imperforate stamps had the same "types" as the perforated ones because they were made from the same plates. No Franklin-head stamps were printed using the offset method.

Stamps Without Perforations

Some stamps were issued in sheets with no perforations between them. These are called imperforate stamps. The Washington–Franklin series includes several imperforate stamps, mainly in 1-cent to 5-cent values.

These stamps were made for vending machine companies. These companies would buy the imperforate sheets and then add their own special perforations. Companies like Schermack, Mail-O-Meter, and Brinkerhoff had their own patented machines. There were at least seven such companies.

Imperforate stamps were sold in full sheets of 400 stamps or in long rolls (coils) of 500 or 1000 stamps. Until 1918, they were printed from flat plates. After that, they were made on a rotary press from continuous rolls of paper. Imperforate coils from the rotary press are much rarer than those cut from full sheets.

Coil Stamps

Coil stamps come in long strips, either side-by-side or one above the other. They are rolled into a coil and sold at the post office. This made it easier for clerks and businesses to use many stamps at once. Coil stamps also worked well in vending machines.

Vending machine companies complained that coil stamps with standard perforations (size 12) tore too easily. So, in 1910, the Post Office introduced a much coarser perforation size: 8½. But this was too hard to tear! So, from 1914 on, a finer size 10 perforation was used for coils.

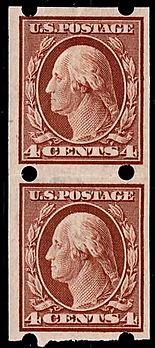

From 1908 to 1914, coil stamps were printed on Flat Plate presses in sheets of 400. These sheets were then cut into strips for coiling. In 1915, the Bureau started printing coil stamps from continuous rolls of paper using the Rotary Press. This press used curved printing plates. This stretched the stamp pictures slightly, making them a bit longer than stamps from a flat-plate. You can see the difference if you put them side by side.

Coil stamps can have perforations horizontally (stamps one above the other) or vertically (stamps side by side). They were made from the same paper as regular sheet stamps. Coil stamps ranged from 1-cent to 10-cents. The 1-cent to 5-cent coils were made almost continuously. The 10-cent coils were only issued twice: once as a yellow Washington-head stamp in 1908, and once as a 10-cent yellow Franklin-head coil in 1916.

| Denomination | 1914 SL-Wmrk Perf.10 Hz |

1914–15 SL-Wmrk Perf.10 Vrt |

1915–16 DL-Wmrk Perf.10 Hz |

1914–16 SL-Wmrk Perf.10 Vrt |

1916–19 SL-Wmrk Perf.10 Hz |

1916–22 Un-Wmrk Perf.10 Vrt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 cent | 441 – W | 443 – W | 448 – W | 453 – W | 486 – W | 490 – W |

| 2 cents | 442 – W | 444 – W | 449 – W | 453 – W | 487–88 – W | 491–92 – W |

| 3 cents | – | 445 – W | – | 456 – W | 489 – W | 493 – W |

| 4 cents | – | 446 – W | – | 457 – W | – | 495 – W |

| 5 cents | – | 447 – W | – | 458 – W | – | 496 – W |

| 10 cents | – | – | – | – | – | 497 – F |

DL-Wmrk = Double-line watermark / SL-Wmrk = Single-line watermark / Un-Wmrk = No watermark

Numbers for stamps from Scotts Specialized US Stamp Catalogue

Notes:

- Each year's series had 1c and 2c stamps with both horizontal and vertical perforations. Other values (3c to 10c) mostly had vertical perforations.

- There is only one example each of the Washington 3c, 4c, and 5c stamps with horizontal perforations.

- Neither the Washington-head nor Franklin-head 10-cent coil was ever issued with horizontal perforations. They only existed with stamps next to each other on a coil.

The Orangeburg Coil

A 3-cent Washington-head coil stamp from 1911 is known as the Orangeburg coil. It was printed on a flat-plate press on single-line watermarked paper. It had vertical, size 12, perforations. The Post Office made only a small amount of these stamps. They sold them all to the Bell Pharmaceutical Company. This company used 3¢ coil stamps to mail product samples to doctors.

The exact number of these stamps made is unknown. The earliest known use was on April 27, 1911. Because these stamps were used for third-class mail, most were thrown away. Stamp collectors didn't know about this stamp for about two years. So, very few were saved in new condition, which makes them very rare today. About twelve covers (envelopes with the stamp used) have been confirmed as real. The Orangeburg coils are the rarest coil stamps of the Washington–Franklin issues.

Private Perforations

Starting on January 3, 1911, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing issued 1-cent and 2-cent imperforate stamps. These were specifically for seven different private companies that made coil-stamp vending machines. Each company used its own unique perforations.

For the 1-cent stamps, these companies used 18 different types of private perforations. For the 2-cent stamps, there were 19 types. These special perforations were designed to fit the machines. They were added to the imperforate sheets after the sheets were cut into strips. Joseph Schermack is often given credit for making the first coil stamp vending machine. Private perforations were used until the 1920s. They are an interesting part of U.S. postal history.

There are no official records of how many of each private perforation type were made. However, how rare they are is known from years of stamp sales. The Farwell type 3A2 is the rarest private perforation. Fake perforations added to imperforate stamps are common for some types. This is because adding fake perforations can make a common imperforate stamp seem much rarer and more valuable.

Most vending machine companies made several different types of perforations. For example, Schermack made five types, Mail-o-meter made six, and Brinkerhoff made four. The John V. Farwell Company made eleven types, and the U.S. Automatic Vending Company made four. Only the Attleboro company and The International Vending Machine Company each made just one type.

2- and 3-Cent Stamp Types

On the 2-cent and 3-cent Washington-head stamps, some engraved pictures look similar but have small differences in their lines. These are called types. Type I stamps are only found on flat plate printings. Types II and III are mostly found on rotary press and offset printings. This is because they were made from photo plates taken from the original printing plates. The 2-cent Type II stamp is not found on a flat plate stamp.

Because the 2-cent and 3-cent stamps were used so much, the printing plates wore out often. They had to be replaced. Even though new plates were made from the same original design, they would be slightly different. This was due to the bending process needed to fit the plate around the rotary press printing cylinder. Also, the original design (die transfer) itself would wear down from repeated use.

There are eleven different "types" of stamp designs for the 2-cent and 3-cent values. The differences are in Washington's face, his Toga, and the shading lines on the stamp design. Finding these differences usually needs a magnifying glass. Most of these "types" are common. But two types are rare and valuable: a 2-cent, 1916 issue, type II, and a 2-cent 1919 issue, type II. Because these differences are so small, valuable stamps can go unnoticed for years. They sometimes turn up in regular stamp collections, but this is very rare.

Unusual Stamps in the Series

A few Washington–Franklin stamps were made later in the series. They don't fit neatly into the other groups because they have unique features. These features are not just about perforation size or paper type.

- In 1917, the New York Post Office sent back some imperforate 2-cent stamps from the 1908–09 series. Instead of giving credit, the main Post Office perforated them with the current size (size 11). Then, they sent them back to New York. This created a new, rare stamp.

- For the first time, three stamps had two different perforation sizes: 11 x 10. These were 1-, 2-, and 3-cent Washington-heads. They were issued on June 14, 1919. They are the only three stamps in the series with this special dual perforation.

- In 1920, a 1-cent Washington-head stamp was issued with perforations of size 10 x 11. This makes it the only stamp in the entire series with this specific setup. It's one of only four stamps with a "compound" or dual perforation.

- In 1921, 1-cent and 2-cent Washington-head stamps were issued. They were on unwatermarked paper with size 11 perforations. These stamps were made from leftover paper from the rotary press. Pictures from curved printing plates are slightly longer than those from a flat plate. The only way to tell these stamps apart from the 1918 size 11 printing is to measure them. They are 19½ mm wide by 20 mm tall. You can also compare them to a flat-plate printing.

- In 1923, the Post Office released the last Washington–Franklin stamp. It also became the rarest non-error stamp in the series. It was printed on unwatermarked paper with size 11 perforations. You can only tell it apart from the 1-cent 1918 stamp (which also has unwatermarked paper and size 11 perforations) by measuring its design. It is 19 mm wide by 23½ mm tall.

Rare Perforation Errors

When the Post Office changed the perforation size from 12 to 10 in 1914, a few sheets were perforated with one size horizontally and the other vertically. These were errors. They included 1¢, 2¢, and 5¢ stamps that were perforated 12×10 (12 horizontally and 10 vertically). There were also 1¢ and 2¢ stamps perforated 10x12. All five of these are very rare. The 2¢ perforated 10×12 stamp is one of the rarest U.S. stamps. Only one used copy has been confirmed.

The 5-Cent Color Error, 1916–1920

During the making of the 1916–17 series, three pictures on one 2-cent printing plate became very worn. When these three pictures were replaced, the worker accidentally put 5-cent pictures onto the 2-cent plate. This error wasn't noticed for several weeks.

Because of this, three different carmine-colored 5-cent stamps were released:

- The perforated 10 stamp from 1916–17.

- The imperforate stamp from the same years.

- The perforated 11 stamp from 1917–20.

The imperforate version is the rarest of these. Very few collectors have ever seen one.

Watermarks in Paper

Watermarks are hidden designs in paper. They are made when the paper is wet, usually by pressing an emblem or letters into the pulp. The part of the paper with the watermark is thinner than the rest. You can often see watermarks by holding the stamp up to a light. But some are hard to see and need a special fluid. Watermarks were first used by governments to prevent fake documents and money.

The U.S. Post Office started using a double-line watermark with the letters USPS in 1895. This same double-line watermarked paper was used for the 1908 and 1909 Washington–Franklin stamps. In 1910, the watermark changed to a single-line one with smaller letters. This was partly because the double-line watermark weakened the paper at the perforations. It also caused the paper to shrink unevenly after printing.

The Bureau used only two types of watermarks for the Washington–Franklins, both with USPS. Watermarks on U.S. stamps are usually not seen with the naked eye. You need special fluid to see them clearly. This helps tell stamps apart that look the same in color, perforation, and value. For example, a 3-cent, 1908 stamp with a double-line watermark looks identical to a 3-cent, 1910 stamp with a single-line watermark without checking the watermark.

The Washington–Franklin stamps were the last U.S. stamps to use paper with the USPS watermark. Using watermarks was stopped in 1916, during World War I. This was done to save money, as watermarked paper was more expensive. The savings by the end of the year were significant.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |