Waterloo Creek massacre facts for kids

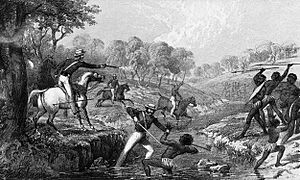

The Waterloo Creek massacre (also called the Slaughterhouse Creek massacre) was a series of violent events in Australia. It happened between December 1837 and January 1838. These clashes involved mounted police, local settlers acting as vigilantes, and Indigenous Gamilaraay people. The events took place southwest of Moree, in New South Wales, Australia.

There has been a lot of disagreement about what exactly happened. People have different ideas about how many people died and if the actions were legal. The discussions about Waterloo Creek became important again in the 1990s during a time called the "history wars" in Australia.

Contents

What Happened at Waterloo Creek?

A group of Sydney mounted police was sent out. They were ordered by Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass, who was acting as the leader of New South Wales. Their job was to find Namoi, Weraerai, and Kamilaroi people. These Indigenous groups were believed to have killed five stockmen. The killings happened on new farms (called pastoral runs) in the upper Gwydir River area of New South Wales.

Major James Nunn led the police group, which had two sergeants and twenty troopers. After two months, they arrested 15 Aboriginal people along the Namoi River. They let most of them go, but one person was shot while trying to escape.

Most of the Kamilaroi people managed to get away from the police. So, Major Nunn's group, along with two stockmen, chased them for three weeks. They went from Manilla on the Namoi River north to the upper Gwydir River.

On the morning of January 26, the Aboriginal people surprised Nunn's group. Corporal Hannan was hurt in the leg by a spear. In return, four or five Aboriginal people were shot and killed. The Aboriginal people ran down the river. The police regrouped, got more weapons, and chased them. Lieutenant George Cobban, the second-in-command, led this chase.

Cobban's group found the Aboriginal people about a mile down the river. This spot is now known as Waterloo Creek. A second fight happened there. This clash lasted for several hours. No Aboriginal people were captured.

Was the Force Used Fair?

At that time, there was no special law (like martial law) that allowed the police to use extreme force. Police were only supposed to use enough force to protect people or property. No one had the right to kill others without a good reason.

People suspected that the police might have used too much force. They might have acted more like a military group than a regular police force. This meant they might have hurt people who were not a big danger.

Official Investigation into the Events

On March 5, 1838, Major Nunn gave a report about his trip to the new Governor Gipps.

Within a month, the government of the Colony (called the Executive Council) agreed to a suggestion. Their Attorney General, Mr. J. H. Plunkett, said there should be an official investigation into the expedition, including the deaths of the Aboriginal people.

The government in the Colony and the British government in England wanted to make sure the law applied to Aboriginal people. They wanted them to be treated like other "British subjects" in the Colony.

On April 6, 1838, the Executive Council decided to announce that there would be an investigation (like a coronial inquiry) into the death of any Aboriginal person killed by a Colonist. This would be the same as when a Colonist died suddenly or violently. However, they delayed announcing this investigation. They decided to wait until the "public excitement" about the executions of the Myall Creek murderers had calmed down.

On August 14, 1838, another group, the Legislative Council, set up a Committee of Inquiry. This committee was to look into "the present state of Aborigines." The Anglican Bishop, William Broughton, led this committee.

Governor Gipps's own investigation into Nunn's expedition was also delayed. He said he couldn't get police officers to testify because they were needed elsewhere. Also, he didn't want to upset the police volunteers, as policing depended on them back then.

Away from the cities, settlers were also starting to take the law into their own hands. Some people believe that law and order were breaking down, making it hard for the New South Wales government to control things.

Even though the Nunn investigation started again on July 22, 1839, at the Merton Courthouse, no one was found guilty. The matter was dropped. Only Lieutenant Cobban and Sergeant John Lee gave eyewitness accounts of the main deadly clash. No further court cases came from this investigation.

Attorney General Plunkett did not want to charge anyone from Nunn's group. This was because of the long delays, a lack of clear evidence, and public opposition.

The Executive Council decided not to take any more action. They accepted that the Aboriginal deaths at Waterloo Creek happened because the police, led by a military officer, acted honestly. They believed the police were following orders and doing their duty to stop an "aggressive attack" by Aboriginal people, even if they made mistakes.

Police Statements About the Event

Lieutenant Cobban said he rode to the back of the group. He found many Aboriginal weapons hidden in the bush and took them. When he returned to the river, he admitted seeing two Aboriginal people shot while trying to escape. He believed that at most three or four Aboriginal people had been killed in the conflict.

Sergeant John Lee was with the main police group that chased the Aboriginal people into the river. He claimed that forty to fifty Aboriginal people were killed.

Historians' Views Later On

More recently, historians and other experts have given different ideas about where the conflict happened and how many people died.

- R. H. W. Reece: Believed the fight was where Slaughterhouse Creek and the Gwydir River meet. He thought 60 or 70 Aboriginal people were killed.

- Lyndall Ryan: Thought Sergeant Lee's estimate of 40 to 50 killed was the most accurate.

- Roger Milliss: Believed 200-300 Gamilaraay people were killed around Snodgrass Lagoon, near the Lower Waters of Waterloo Creek.

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Waterloo Creek para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |