Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion State Historic Site |

|

|---|---|

The mansion in 2013

|

|

| Location | 375 Little Harbor Road, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, US |

| Website | Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion State Historic Site |

|

Wentworth-Coolidge Mansion

|

|

| Built | 1750 |

| Architectural style | Colonial |

| NRHP reference No. | 68000011 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 24, 1968 |

| Designated NHL | November 24, 1968 |

The Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion is a large, historic house with 40 rooms. It was once the home and workplace of Benning Wentworth, who was a colonial governor of New Hampshire. He also ran a farm from this location.

The mansion sits right on the water at 375 Little Harbor Road, near Portsmouth, New Hampshire. It's special because it's one of the few homes of a royal governor that still looks much like it did long ago. This site is now a New Hampshire state park. In 1968, it was named a National Historic Landmark, which means it's a very important place in American history. Today, the state helps manage the mansion with a group of volunteers.

Contents

A Look Back at the Mansion's History

In 1741, New Hampshire became its own separate colony, and Benning Wentworth became its first royal governor. He wanted a special building for the government in Portsmouth, but the local leaders said no.

So, in 1741, Governor Wentworth rented a fancy brick house in Portsmouth. This house, now called the MacPheadris–Warner House, served as his home for about 17 years. He tried to buy it for the government, but the price was too high.

Around 1750, Governor Wentworth's son, John, started buying land outside Portsmouth. This land became a large farm with a house near a water channel called Little Harbor. Wealthy people in Portsmouth often bought country farms like this.

The mansion wasn't built all at once. It was made by moving several existing buildings to the site and joining them together. New parts were added too. This is why the house looks a bit unusual and not perfectly even. Experts believe it's a mix of at least four or five older buildings.

By 1753, the house by the water was comfortable enough for Governor Wentworth to live in. He likely moved there permanently around 1759. From this new home, he continued to sign important papers that created new towns in New Hampshire and Vermont.

Today, you reach the house by driving through a forest, which makes it feel far away. But in Wentworth's time, the land was mostly clear farmland. It was also much easier and faster to get to Portsmouth by boat than by land. The water around the house, even in the calm-looking harbor, had strong currents.

Governor Wentworth owned the property until he passed away in 1766. His second wife, Martha Hilton, inherited it. She later married Michael Wentworth. The house's contents were sold in 1806, giving us clues about what was inside.

In 1803, the house and land were advertised for sale. Martha passed away in 1805 and left the property to her daughter, also named Martha. This younger Martha married Sir John Wentworth in 1802. A map from 1812 shows the property belonging to John Wentworth.

The Cushing family bought the property in 1816 and ran it as a farm. By the 1840s, they started showing the old mansion to visitors. This was one of the first times a historic house in America was opened to the public. It showed a growing interest in preserving history.

In 1886, John Templeman Coolidge III and his wife bought the property. They worked with William Sumner Appleton, who started a group to save old New England buildings. They fixed up and added to the mansion. This was part of a movement to celebrate colonial history.

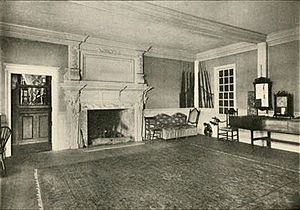

Photos from 1937 show the house filled with old furniture, arranged in a style popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Coolidge's second wife, Mary Abigail Parsons Coolidge, gave the Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion to the state of New Hampshire in 1954.

How the Mansion is Organized

From the outside, the mansion looks very different from other grand houses built in the mid-1700s. Most wealthy people at that time preferred houses that looked perfectly balanced and even. For example, the John Paul Jones House, built around the same time, shows this balanced style.

The mansion's unusual look came from joining different buildings together and adding new parts. To make it look more uniform, the outside was covered with clapboards. Inside, the rooms had plaster walls and fancy wooden trim, common in high-end homes of that time. A carpenter named Neal, who lived in the house as a servant, did this work.

Inside, the house might seem like a maze, but the rooms were carefully planned. They were arranged in three main sections: one for formal parties, one for family life, and one for servants' work. Each section had its own entrance and staircase. This way of organizing a large house came from European traditions.

Governor Wentworth was likely aware of these grand European styles. He had connections to British culture and had traveled to London. People who didn't like him sometimes called him a "Spanish grandee" because of his fancy style and European connections.

The formal style usually had impressive public areas like a grand hall and a large room for guests. Smaller, fancier rooms were for private use, like bedrooms or studies. At Little Harbor, Governor Wentworth followed this idea of different rooms for different purposes, even with the house's unusual shape and sloped land.

The Formal Wing: For Important Guests

The part of the house closest to the water seems to be made from another reused building. It has a tall entrance area, a grand room for parties, and a long room with two smaller rooms, plus attic spaces.

The main door to this wing is very fancy, with decorative columns and a triangular top. This shows it was the most important entrance. It doesn't face the water directly but points towards the old wharves and driveway. This made it easy for guests arriving by land or water to find.

Inside, the entrance area has a staircase with a fancy railing, built-in benches, and racks for guns above the doors. The benches were for servants to wait or for visitors to sit while waiting to see the governor.

The gun racks, filled with flintlock muskets, were an impressive display. They reminded everyone that the governor was in charge of the colony's army. These guns were said to have been captured from a French fortress in Canada. This story fit well with the interest in colonial history during the Colonial Revival period.

To the right of this entrance are the mansion's largest rooms. They have high ceilings, rich wooden details, and tall windows. Both rooms have built-in corner cupboards, likely used for serving drinks like punch. This suggests these rooms were used for entertaining.

The first room is square and was probably called a "parlor" or "great parlor." Today, it's known as the Council Chamber, though there's no proof the governor's council ever met here. This room felt very important. A large portrait of Governor Benning Wentworth, painted in 1760, originally hung here. It was seven feet tall and four feet wide, making him look larger than life. A copy hangs there today.

The most impressive part of this room is the fireplace. It has fancy carvings and columns, inspired by a famous British mansion called Houghton Hall. This design showed that Governor Wentworth wanted to connect himself with the powerful British government.

This room also had two special corner cupboards, called "beaufaits," for serving food and drinks. Their unique design was only found in this house.

Even though the room wasn't actually a council chamber, it was furnished in the 1980s to look like one. It had reproduction furniture and flags. These meetings were more about celebrating history than bringing back old traditions.

The next room in this formal wing is long and narrow, with tall windows overlooking the water. It has no fireplace, suggesting it was used in warmer seasons, perhaps as a summer parlor. Its two serving cupboards confirm it was for entertaining. Its long shape and two small side rooms suggest it might have been a ballroom for dancing. The small rooms could have been for cards or as cloakrooms.

This long room has original wallpaper with a fancy pattern and glitter. It was likely added in the late 1700s or early 1800s.

The Family Wing: For Everyday Life

From the main entrance area, a few steps lead up to another part of the house, the family wing. This section has a nice parlor, a more casual everyday parlor, and a small area that might have been an office. These rooms together made a comfortable family home. Because this wing is higher up but has the same ceiling height, the rooms feel cozier and were easier to heat.

The parlor has bold wooden trim on its lower walls, painted sky blue. This strong style might have been what Governor Wentworth liked, or it could be similar to the trim in the Warner House where he lived before.

The parlor walls have original red-and-yellow wallpaper with a large pattern. During restoration, it looked like this wallpaper might have been moved from another room. The room also has a harpsichord, a musical instrument. It was added by Martha's second husband, Michael Wentworth, who loved music. Even though it wasn't Governor Wentworth's, people thought it was because it was so old.

Off the parlor is a small, lockable room with shelves. This "china room" was like a very large cupboard. It likely held locked containers of tea, sugar, and alcohol, along with fancy silver and china. These items were expensive and often associated with women. In those days, tea was very costly, so keeping it locked up made sense.

Dining rooms were not common yet. Families would eat in different rooms depending on the occasion. So, a large china room was useful for keeping the best dishes safe and separate from the kitchen.

The family entrance has an outer and inner hall with a staircase. This entrance was hidden from the wharves and main road, guiding visitors to the formal entrance. The wooden trim here is simpler, fitting its everyday use.

Behind the stairs is a small room with a small fireplace. It was likely a study or office. A deep closet in this room has a window that lets in light from the entrance area. People used to say the governor could "spy" on guests from here. But it was probably just to light up the dark closet, as lighting with candles or lamps was dangerous.

Beyond the stair hall is a back parlor. In Governor Wentworth's time, this was probably an everyday sitting room. It had nice wooden panels and trim, but not as fancy as the more important rooms. Families used these rooms daily for relaxing, talking, sewing, and eating casual meals. Dedicated dining rooms were just starting to appear in Britain and wouldn't be common in New England until much later.

Today, the back parlor is furnished to look like a dining room from a later period, showing how it might have been used by Michael and Martha Wentworth.

Above these three main rooms are three bedrooms. They have simpler wooden trim, with the fanciest bedroom above the parlor and plainer ones above the other rooms.

The bedroom above the parlor has pieces of the same red-and-yellow wallpaper as the parlor below. It's decorated with fancy yellow fabric for the bed, curtains, and chairs, showing a very high-end style of the time.

The Service Wing: For Work and Servants

The back part of the house was the service wing, for household work. Steps here also follow the slope of the land, and the rooms have lower ceilings than the other wings. This section includes a large kitchen with a big cooking fireplace, small storage rooms, a brick-floored room for food storage or dairy, and a small French-style "potager" or stewing kitchen. This stewing kitchen had iron fire baskets built into a brick counter for cooking, but no chimneys.

The stew kitchen is thought to be connected to John King, a French cook Governor Wentworth hired. King would visit the mansion a few times a week to cook for the governor. This type of kitchen is very rare in New England and is more common in places with strong French influences. It has a door to the dining room, a pass-through to the main kitchen, and windows for air.

Behind these rooms is the main kitchen. It has a large table built around a central post. There are also two smaller rooms, possibly pantries. The combination of a large fireplace, two ovens, and the French stew kitchen meant the house could handle big parties and meals.

Upstairs in this wing are rooms of different sizes with the plainest wooden trim. These were likely for servants and for work.

This back service wing has its own entrance and staircase. This door faces away from the family entrance and is hidden from the main road and wharves. This made sure that visitors would use the formal entrance. It also meant that servants and enslaved people coming and going from the barns, fields, and wharves wouldn't be seen by the family or guests. This separation of people by their status was unusual for the time in New England.

When the Coolidge family owned the house, they built a new carriage house and driveway. This new driveway is what visitors use today. This means the service entrance is now the most obvious door, and the formal entrance is hidden. This completely changes the original impression of the house.

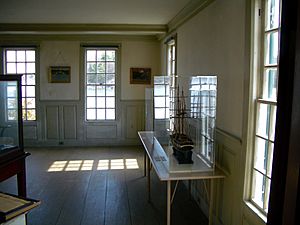

Two more wings were added during the Coolidge family's ownership. A simple service wing was added behind the kitchen. At the water end of the house, a guest bedroom was added with windows overlooking the water. This room now displays items from the Coolidge era.

Outdoor Spaces: Gardens and Views

The outdoor areas also had a special arrangement. There was a small garden, a large garden, and a roof deck.

An old map from 1812 shows the gardens. The small garden was between the formal entrance and a building by the water. It was called a "Flower Garden."

A much larger garden was south of the house. It was a long rectangle with paths, dividing it into six sections. It might have been for vegetables, herbs, or flowers. In 1803, the property was described as having both a large garden and a flower garden with "all kinds of the best growth of Fruit Trees, Grape Vines, &c."

Today, the small garden area is a flat lawn. Most of the large garden is now covered with trees.

One plant that might be a survivor from those gardens is the lilac. The mansion is traditionally believed to be where lilacs were first brought to New Hampshire. Their abundance around the house led to the lilac being chosen as the state flower in 1919.

Above the best bedroom was a flat roof deck. You could reach it from a staircase in the family wing. This deck offered amazing views of the garden, orchards, farm fields, the water, and even the sea. This kind of view was popular in new garden styles in Britain at the time. It's the earliest known example of a roof deck in New England.

Building and maintaining this deck was probably easy in Portsmouth, a shipbuilding city. But the harsh New England weather eventually caused problems. At some point, the roof deck was covered with a sloped roof to shed snow and rain. Leaks from the deck might explain why the wallpaper in the bedroom below was damaged.

An advertisement from 1803 described the property: "That pleasant, agreeable and well known SEAT, at Little Harbor. The large and spacious MANSION HOUSE, formerly belonging to Gov. Benning Wentworth... a large and extensive Garden, – likewise, a beautiful Flower Garden, adjoining the House, both containing all kinds of the best growth of Fruit Trees, Grape Vines, &c. A Wharf with convenient Stores thereon, two large and commodious Barns, Cyder House, and other out and convenient Buildings, with two Wells of excellent water. – The above containing about one hundred acres of Tillage, Mowing and Pasture Land, together with two excellent Orchards, the whole enclosed with a strong and well built stone Wall. The situation is delightful and romantic, commanding a grand prospect of the sea and adjacent country."

This description suggests that many of these features were from Governor Wentworth's time and were kept up by later owners.

The way the mansion is designed, its decorations, and how the outdoor spaces were arranged all show that it followed a clear, organized plan, even with its unusual outside appearance.

Today, the house is open to the public in the summer. Tours usually start at the kitchen door. This gives visitors a different experience, moving from the less important work rooms, through the family rooms, to the impressive formal rooms. This is the opposite of how important guests would have experienced the house long ago.

Drift Contemporary Art Gallery

An old barn on the property was turned into a visitor center, event rooms, and offices in the late 1990s. Around 2000, it became a gallery for modern local art in the summer and an art school in the winter. After the gallery manager retired and passed away, the space was empty until 2013. That's when the Drift Gallery moved in.

The Drift Gallery now runs the space as a private art gallery, working with the mansion. It has shown art by many modern artists, including Robert Wilson and Ryan Jude Novelline. The gallery also offers educational programs, like a week-long art residency. This residency honors the art community that John Templeton Coolidge started in the late 1800s.

More to Explore

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New Hampshire

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Rockingham County, New Hampshire

- List of New Hampshire historical markers (176–200) § 194: Wentworth–Coolidge Mansion

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |