William Barley facts for kids

William Barley (born around 1565, died 1614) was an English bookseller and publisher. He started his career as a draper (someone who sells cloth) in 1587. Soon after, he began working in the book business in London.

William Barley often faced legal problems throughout his life. He was involved in a big argument between two important groups: the Drapers' Company (for cloth sellers) and the Stationers' Company (for printers and booksellers). This argument was about whether drapers could also be publishers and booksellers.

Scholars have different ideas about Barley's role in publishing music during the Elizabethan era (when Queen Elizabeth I ruled). Some say he was "full of energy and ambition," while others thought he was "somewhat tricky." People at the time criticized the quality of some of his first music books. However, he was still an important person in the music publishing world.

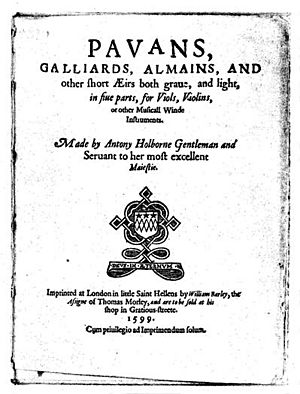

Barley later worked with Thomas Morley, a famous composer who also had a special permission (a printing patent) to be the only one to publish music. Barley published Pavans, Galliards, Almains (1599) by Anthony Holborne. This was the first music book for instruments (not just voices) printed in England. His partnership with Morley helped him claim rights to music books, but it didn't last long. Morley died in 1602, and some publishers didn't respect Barley's claims after that.

Contents

William Barley: A Printer's Story

Early Life and Business Challenges

William Barley was likely born around 1565, possibly in a place called Warwickshire. We don't know much about his very early life. By 1587, he was in London. He finished his training with the Drapers' Company that year.

Working in London and Oxford

Barley learned about bookselling from Yarath James, a smaller publisher. James had a shop in Newgate Market, London. Both James and Barley were interested in publishing popular songs called ballads. Barley published many of these during his life. By 1592, Barley had his own shop in London. He ran his business from this shop for the next 20 years.

Barley also opened a branch shop in Oxford. This caused problems with the authorities there. He probably had his assistant, William Davis, run the Oxford shop while he stayed in London. In 1599, Davis was arrested because Barley hadn't registered as a bookseller with Oxford University. However, Barley and Davis fixed this. In 1603, they were given "privileged person" status at Oxford University. This meant they could do business without the town's local rules getting in the way.

Barley also had trouble with the London authorities. In 1591, there was an order for his arrest, but we don't know why. He was also caught in a long-running fight between the Drapers' Company and the Stationers' Company. The Stationers' Company had a special right to control all publishing. But the Drapers' Company wanted its members to be able to publish and sell books too. They said it was a "custom of the City" for their members to work in the book trade.

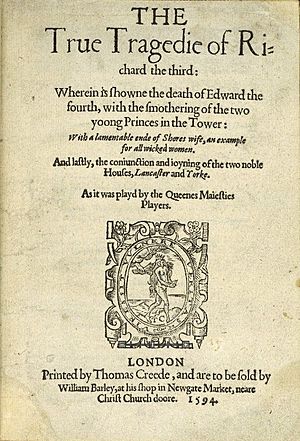

From 1591 to 1604, Barley was involved with at least 57 different books. It's sometimes hard to know exactly what his role was. Some books were printed "for" him, others were "to be sold by" him, and two even said they were printed "by" him. He worked with important printers like Thomas Creede and John Danter. With Creede, Barley helped publish A Looking Glass for London and England (1594) and The True Tragedy of Richard III (1594).

During this time, Barley didn't register any of these books in the Stationers' Register. Registering a book meant a publisher officially owned the rights to it. He probably didn't register them because of the fight between the Drapers' and Stationers' companies. The Stationers' Company saw it as a special privilege for their members to register books. So, Barley relied on others, like Creede, to register the titles. We don't know if Barley just sold the books for them or if he secretly owned the rights to some of them.

In 1595, the Stationers' Company fined Barley 40 shillings for publishing books without permission. Three years later, they sued him and another draper, Simon Stafford. They were accused of publishing "privileged books" (books that only certain people had the right to print). A search of Barley's old shop found 4,000 copies of the Accidence, a Latin grammar book that was protected by a special right. Even though Barley said he was innocent, he, Stafford, and others were found guilty and sent to prison. This lawsuit showed that the Stationers' Company had strong control over the book trade.

Stafford and other draper-booksellers joined the Stationers' Company soon after so they could keep working. But Barley didn't join until 1606. Experts wonder why he waited so long. Some think the Stationers' Company didn't want him because he didn't have printing experience. Others believe his partnership with Thomas Morley, who had a special royal permission for music publishing, helped him avoid legal problems. The Stationers' Company couldn't stop books published under a royal grant.

Publishing Music in Elizabethan England

In England during Queen Elizabeth's time, music printing was controlled by two special permissions from the queen. One was for metrical psalters (songs based on psalms), and the other was for all other music and music paper. Only the people who held these permissions, or those they allowed, could legally print music. This was a monopoly, meaning they had exclusive control.

After printer John Day died in 1584, the permission for metrical psalters went to his son Richard Day. The more general music permission was given to composers Thomas Tallis and William Byrd in 1575. Even with this special right, Tallis and Byrd didn't do well with their printing. Their 1575 collection of Latin songs, Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur, didn't sell well and lost money. After Tallis died in 1585, Byrd continued with the permission. This special right ended in 1596, which allowed other publishers like Barley to try their hand at music publishing.

Early Music Books and Problems

In 1596, even though he didn't have the right music fount (type for printing music), Barley published The Pathway to Music (a music theory book) and A New Booke of Tabliture (a guide for playing the lute and similar instruments). The second book included music by John Dowland, Philip Rosseter, and Anthony Holborne. Both books had many mistakes. For A New Booke of Tabliture, Barley seems not to have gotten permission from the composers.

Dowland said his lute lessons in the book were "false and imperfect." Holborne complained about "corrupt copies" of his work being printed by a "mere stranger." Modern music experts have called the book "frustrating" and "shady." Thomas Morley also criticized The Pathway to Music, saying the author should be "ashamed" and that "there is scarcely a page that makes sense in the whole book." Despite their flaws, these books were important for bringing music guidebooks to London.

Two years later, Thomas Morley received the same music printing permission that Byrd had held. It was surprising that Morley chose Barley as his partner, instead of experienced printers like East or Peter Short, who had worked with Morley before. Morley might have wanted help challenging Richard Day's permission for metrical psalters. At that time, East and Short were members of the Stationers' Company, which was strongly supporting Day's monopoly. But Barley was not a stationer.

In 1599, Barley and Morley published The Whole Booke of Psalmes and Richard Allison's Psalmes of David in Metre. The Whole Booke of Psalmes was a small pocket-sized book, mostly based on East's 1592 version. This book, even though it was copied without permission and had small errors, showed Barley's skill. One music expert noted that if Barley is criticized for being tricky, he should also be praised for his "musical imagination" in making such a large work fit into a small book. In Allison's work, Barley and Morley claimed they had the only rights to metrical psalters. This made Day angry, and he sued them. We don't know the result of the lawsuit, but Barley and Morley never published another metrical psalter.

Barley's Partnership with Thomas Morley

Under Morley, Barley published eight books. The covers of these books said they were "printed by" Barley, but looking closely at the printing styles, this seems unlikely. At least two of the books have designs that look like they belong to a London printer named Henry Ballard. Among these eight books, Holborne's Pavans, Galliards, Almains (1599) was very important. It was the first music book for instruments (not voices) printed in England. Also, the first edition of Morley's famous The First Booke of Consort Lessons (1599) was published during this time.

Joining the Stationers' Company

Barley's partnership with Morley didn't last long. By 1600, Morley had chosen East as his new partner. Two years later, Morley died, and his music permission ended. Without Morley's protection, Barley likely faced more pressure from the Stationers' Company. His money problems also grew after he lost a lawsuit to a cook named George Goodale, who wanted an 80 pounds debt paid. Because of this, many of Barley's belongings, including books and paper, were taken away. Barley published much less from 1601 to 1605, only releasing six books.

New Rules and Old Disputes

Barley probably decided it was useless to keep fighting the Stationers' Company. On May 15, 1605, he asked the Drapers' Company to let him switch to the Stationers' Company, and they agreed. On June 25, 1606, the Stationers' Company accepted him as a member. On the same day, the Company's court, which settled arguments between members, helped resolve a lawsuit Barley had against East. This lawsuit was about the copyrights (legal rights) to certain music books.

East claimed that since he had properly registered the books in the Company's register, the rights belonged to him. Barley disagreed, saying the rights were his because of his partnership with Morley, who had held the royal music permission. The court reached a compromise: if East printed any of the books, he had to mention Barley's name, pay Barley 20 shillings, and give him six free copies. On the other hand, Barley could not publish any of the books without East's permission.

Later Life and Legacy

Even though the settlement recognized Barley's claim to Morley's music permission, he found it hard to use his rights, even as a new member of the Stationers' Company. Less than half of the known music books published from 1606 to 1613 mentioned Barley's rights. In 1609, Barley took Thomas Adams to the Stationers' court, challenging Adams's copyrights on music books. The court made a similar agreement to the one between East and Barley. However, none of the music books Adams published afterward mentioned Barley's permission.

Barley himself published four books under his permission. In March 1612, one of Barley's servants died, possibly from the plague. After getting some money from the Stationers' Company, Barley moved. Records show he was buried on July 11, 1614. His wife, Mary, and their son, William, were mentioned in the will of Thomas Pavier. Mary Barley later remarried and transferred five of her husband's permissions to a printer named John Beale. Some of Barley's other copyrights might have gone to printer Thomas Snodham.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |