William Benbow facts for kids

William Benbow was an English shoemaker, writer, and political activist. He lived in the 1800s and fought for the rights of working people. He worked with William Cobbett on a newspaper called Political Register. Because of his writings and campaigns, he spent time in prison. Many people believe he was the first to suggest the idea of a general strike to bring about political change.

Contents

Who Was William Benbow?

William Benbow was born on February 5, 1787, in Middlewich, Cheshire. His father, also named William Benbow, was a shoemaker. We don't know much about his first jobs. But he was an ex-soldier.

His Early Beliefs

By 1808, he was giving religious talks in the Newton area of Manchester. He was a Nonconformist preacher. This means he was a Protestant who did not follow the Church of England. He might have been a Quaker. In 1816, he was listed as a top reformer in Lancashire. When he was in prison in 1841, he said he was a married shoemaker with three sons. He also said he was a Baptist.

Fighting for Change: Publishing and Activism

Benbow went to political meetings in London in 1816. He was a representative for a group called the Hampden Clubs. He became interested in a political idea called Spenceanism.

Early Protests and Arrests

He helped plan the Blanketeers protest march in March 1817. This was a march by weavers from Lancashire. After this event, many activists were arrested. Benbow was one of them. There were rumors that big uprisings were being planned in places like Manchester.

In 1818, Benbow sent a petition to Parliament. He explained that he was arrested in Dublin in May 1817. He spent eight months in London prison. Then he was let go without a trial. He didn't have money to travel back home to Manchester.

Becoming a Radical in London

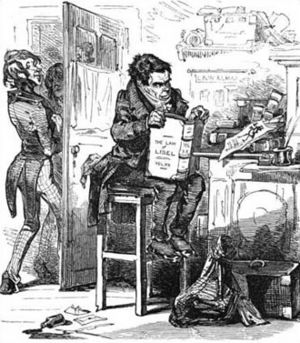

Benbow became a known political activist in London. He worked with William Cobbett. A writer named Samuel Bamford said Benbow spent his time "agitating the labouring classes." This means he encouraged working people at their meetings.

To earn money and support his activism, Benbow worked as a printer, publisher, and bookseller. He also owned a coffee house. He worked closely with writer George Cannon. Benbow printed many of Cannon's works. Some people think Cannon might have written some of the things published under Benbow's name. When William Cobbett left for America in 1817, Benbow continued to publish Cobbett's newspaper, the Political Register, until Cobbett returned in 1820.

Publishing Controversial Works

In 1822, Benbow published a version of Lord Byron's Don Juan. He also published The Natural History of Man by William Lawrence. This book had lost its copyright because it was seen as offensive to religion.

Benbow also had a strong disagreement with the Poet Laureate, Robert Southey. Southey was upset that Benbow reprinted parts of his early poem Wat Tyler without permission. Benbow responded with a pamphlet called A Scourge for the Laureate. In it, Benbow showed how Southey's early poem had radical ideas. This was very different from Southey's later role in the government. Benbow printed his version of Southey's work at his bookshop, the Byron's Head. He also printed a version of Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. This book had been quickly taken off the market by Shelley's wife, Mary, in 1824.

In 1832, Benbow published Crimes of Clergy. This was a collection of his own articles. They were very critical of Church of England ministers. One of these articles, from May 1821, said it was written in King's Bench Prison. In July 1821, Benbow's MP, John Cam Hobhouse, asked the Attorney General to look into Benbow's imprisonment.

The Grand National Holiday

On January 28, 1832, Benbow published a pamphlet. It was called Grand National Holiday and Congress of the Productive Classes. He had joined the National Union of the Working Classes in 1831. His coffee house became a main meeting place for the Union.

Benbow's Big Idea

Benbow often spoke at meetings at Blackfriars Rotunda. He suggested strong actions for political reform. He especially pushed his idea for a "national holiday" and "national convention." By this, he meant a long general strike by working people. He called it a "holy-day" because it would be a sacred action. During this time, local groups would keep peace. They would also choose people to go to a national meeting. This meeting would decide the future of the country.

In his pamphlet, Benbow compared his plan to the ancient Jewish Jubilee year. This year included ideas like forgiving debts and sharing land. The striking workers were supposed to support themselves with savings. They would also use money from local church funds. They would also ask rich people for money. Benbow briefly published a newspaper called the Tribune of the People. It talked about topics for the congress. But it stopped after only three issues.

Later Arrests and Legacy

In April 1832, Benbow was arrested again. This was for planning a Chartist parade and a "general feast." He was tried and found not guilty the next month.

Benbow's popularity went down for a while. But his idea of a Grand National Holiday was used by the Chartist Congress in 1839. Benbow had spent time in Manchester in 1838–39 promoting his pamphlet. The holiday was planned to start on August 12. But on August 4, Benbow was arrested. This was for trying to get workers to join the strike. The Chartists then called off the strike.

Benbow spent eight months in prison. At his trial in Chester in April 1840, he spoke for over ten hours to defend himself. But he was found guilty. He was sentenced to sixteen months in prison. William Benbow, his wife, and his son George moved to Australia around 1853. He passed away in Sydney on February 24, 1864.

See also

- Rotunda radicals

- Blanketeers

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |