William Knibb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Knibb

OM

|

|

|---|---|

Knibb in the centre, to the left is John Burnet and to the right is John Scoble - 1840

|

|

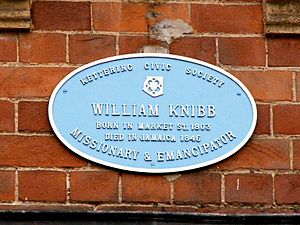

| Born | 7 September 1803 Kettering, England

|

| Died | 15 November 1845 (aged 42) Kettering, Jamaica

|

| Spouse(s) | Mary Watki(n)s |

William Knibb (born September 7, 1803, died November 15, 1845) was an English minister who traveled to Jamaica as a missionary. He is famous for his important work to help free enslaved people in Jamaica.

In 1988, 150 years after slavery was ended in the British Empire, Knibb was given the Jamaican Order of Merit. This is Jamaica's highest award for citizens. He was the first white man to receive this special honor.

Contents

William Knibb's Early Life

William Knibb was born in Kettering, England. His father, Thomas Knibb, was a tradesman. His mother, Mary, was very involved in their local church. William was the fifth of eight children.

William's older brother, Thomas, was also a missionary and teacher in Jamaica. When Thomas sadly passed away at age 24, William decided to take his place. He had a special service in Bristol on October 7, 1824. Just two days before, he had married Mary Watkins. William was only 21 when he and Mary sailed to Jamaica on November 5, 1824.

Starting His Mission in Jamaica

When William arrived, there were already six English Baptist missionaries in Jamaica. There were also many African-Caribbean Baptist leaders and churches. They were continuing the work of George Lisle, a former enslaved person from Virginia. Lisle had started a Baptist church in Kingston in 1782.

Knibb began his work as a teacher at the Baptist mission school in Kingston. He worked closely with other missionaries, Thomas Burchell and James Phillippo. In 1828, he moved to Savanna-la-Mar. By 1830, he became the minister for the Baptist church in Falmouth. When he arrived, about 600 people regularly attended the church. He stayed there as minister until he died.

William Knibb Fights Slavery

The Baptist churches in Jamaica were started by freed enslaved people. They sought help from churches abroad, like the English Baptist movement that William Knibb joined. Jamaica was a big sugar producer, and this relied on slavery. Knibb strongly supported the enslaved people and their fight for freedom.

The terrible curse of slavery has ruined almost everything good. I don't understand how anyone can support such a monster, such a child of hell. I hate it and see it as one of the most awful things that ever shamed the earth. The cruel hand of slavery tries daily to keep enslaved people ignorant.

—William Knibb

Knibb made his feelings very clear. Once, a Black enslaved man named Sam Swiney was wrongly accused of a small crime. Knibb spoke up for him in court. But the local authorities still found Swiney guilty and had him whipped. Knibb refused to let this go. He published the details in a newspaper, even though he was threatened with legal action. His story reached officials in London, who eventually fired the two magistrates responsible.

Knibb and his fellow Baptist missionaries also worked hard to stop new, harsh laws against enslaved people in Jamaica. They helped convince the British Parliament to prevent these laws from being passed.

Because of his actions, Knibb was very popular with the enslaved people. When the church in Falmouth needed a new minister, Knibb's name was suggested. The person leading the meeting said that when he asked for a vote, everyone stood up, raised both hands, and cried. This showed how much they wanted him as their minister.

Speaking Up for Jamaica's Enslaved People

In 1832, the Baptist enslaved people in Jamaica decided to send Knibb back to England. They wanted him to speak for their cause. Once in England, he traveled around England and Scotland, giving speeches at public meetings. He told people the truth about the good work churches were doing in Jamaica. He also spoke about the terrible treatment of the enslaved population.

Knibb's public speeches had an amazing power. People who doubted were convinced, those who were unsure made up their minds, and many hearts everywhere were filled with strong support.

—Peter Masters

Knibb later remembered his efforts.

I was forced from a place of shame and from a dark prison. My church members were scattered, many were killed, and many faithful people were whipped. I came home and will never forget the three years of struggle and constant worry as I traveled across the country telling of the enslaved people's suffering.

—William Knibb

Knibb was asked to speak before committees in both parts of the British Parliament. These committees were looking into the situation in the West Indies.

Knibb's evidence...was so true and strong that it helped more than anyone else's to convince everyone that slavery had to be ended quickly.

—Peter Masters

Slavery Ends!

Finally, in May 1833, a law to end slavery in the colonies was introduced. This law was passed later that year. Slavery was supposed to end on August 1, 1834. However, enslaved people had to go through another six years of 'apprenticeship' before they were fully free. Plantation owners cruelly misused this rule.

A new law was passed in Jamaica to stop the original law's purpose. This Jamaican law prevented full freedom by forcing former enslaved people to work in an apprenticeship system. The money they earned was used to buy their freedom at very high prices, sometimes £60, £80, or even £90. Knibb and others fought against these unfair practices. Because of their efforts, Parliament moved the date for full freedom from 1840 to 1838.

Helping After Freedom

With freedom came huge social changes. Thousands of enslaved children also became free, but there was no education for them. Knibb did what he could, but it was hard because there weren't enough teachers.

When adults gained freedom, they entered a world without education or support systems. Church ministers were often the only people former enslaved people could go to for legal advice. Knibb said, "Often I have had people come to me for advice who have walked twenty miles to ask for it."

Knibb helped raise money to buy thousands of acres of land. This allowed 19,000 former enslaved people to own their own property.

Big Religious Changes

Freedom also brought big religious changes. From 1838 to 1845, there was a religious revival in Jamaica known as the Jamaican Awakening. Many thousands of former enslaved people joined the nonconformist churches. Knibb remembered that "in those seven years, about twenty [Baptist] missionaries helped 22,000 people get baptized after saying they believed in Jesus Christ."

Knibb personally baptized 6,000 people. He also helped translate the Bible into Creole, the language spoken by many formerly enslaved people.

In 1839, the Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society became part of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. This group planned a big meeting in 1840, led by Joseph Sturge. Knibb was invited. Thomas Swan, who led a Baptist church in Birmingham, met Knibb. Swan and Joseph Sturge had worked hard to support Knibb. Knibb had already encouraged his church in Jamaica to free any unpaid workers they had.

Knibb brought two church leaders from Jamaica, Edward Barrett and Henry Beckford, with him to England. These two men spoke to 5,000 people at Birmingham Town Hall. Beckford became the main person in a famous painting that showed the World Anti-Slavery Convention.

By 1845, the Baptists in Jamaica had built 47 new churches. These replaced the ones that had been burned down. Many of these churches, mostly made up of former enslaved people, were financially independent. Knibb's own church in Falmouth grew from 650 to 1,280 members in ten years. Over 3,000 adults had been baptized, and two-thirds of them had gone on to start new churches. The Falmouth church alone helped start six other churches. Knibb himself was involved in starting 35 churches, 24 missions, and 16 schools. In 1845, Knibb bought land to create the village of Granville, Jamaica, named after Granville Sharp.

Death and Lasting Legacy

William Knibb died of a fever in Jamaica on November 15, 1845. He was only 42 years old. He was buried at his Baptist Falmouth Chapel. Eight thousand African islanders attended his funeral. The sermon was given by pastor Samuel Oughton.

In 1988, 150 years after slavery ended in the British Empire, Knibb was given the Jamaican Order of Merit. This was Jamaica's highest award for citizens. He was the first white man to receive this special honor.

This monument was put up by the freed enslaved people, whose freedom and progress he worked so hard for. It was also put up by his fellow workers who admired and loved him, and who are very sad about his early death. And by friends of different beliefs and groups, to show their respect for someone whose good name as a man, a helper of people, and a Christian minister is known in all churches. Even though he is dead, he still speaks.

– The inscription on the tomb of William Knibb at Kettering Baptist Church, Trelawny, Jamaica

William Knibb Memorial High School in Trelawny, Jamaica is named after him.

Images for kids