Women during the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera facts for kids

Women in Spain during the time of Primo de Rivera's rule had very few rights. They faced many unfair rules because of their gender. Even though some women tried to fight for more rights, their groups were small and didn't achieve much at first.

Women did get a small step towards voting rights. On March 8, 1924, a new law allowed some women to vote for the first time in local elections. However, many people thought this was just a trick by Primo de Rivera to get more votes. By the time of the next big elections, this voting right was gone because a new constitution was being written.

Later in the dictatorship, more women started to demand equal rights. Some women also felt that traditional political groups weren't helping them enough. During this time, more girls and women got the chance to go to school, and more women learned to read and write.

Women often faced harassment when they were out in public. Because families needed more money, more women started working outside the home. They even began to go to places that were usually only for men, like cafes and special clubs for learning.

Contents

Spain's Government in the 1920s

The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera was a period when Spain was ruled by a military leader, Miguel Primo de Rivera, from 1923 to 1929. This happened during the time when Spain still had a king, Alfonso XIII. When the king left Spain in 1930, Primo de Rivera's rule ended. This led to a new period called the Second Republic, and new elections were planned for 1931.

Early Years of the Dictatorship (1923-1925)

Women Fighting for Rights

During Primo de Rivera's rule, there weren't many feminist events in Spain. When women did try to organize, some men didn't take them seriously. Groups like the Lyceum Club in Madrid, which promoted women's independence, were even criticized by the Catholic Church. Some men saw these groups as a threat to the way things had always been.

Feminists during this time often focused on quiet but strong ways to challenge traditional ideas about women. Many of them wrote stories or plays to criticize society. Other feminist groups existed, like the Future and Feminine Progressive in Barcelona and the Concepción Arenal Society in Valencia. However, these groups were less known and didn't achieve as much. Most members of these groups were from middle-class families, so they didn't represent all women in Spain.

Women's Right to Vote

On March 8, 1924, a new law called the Royal Decree's Municipal Statue Article 51 was passed. For the first time, it allowed some women to vote in local elections. Women over 23 who were not controlled by a male guardian or the government could be listed as voters. Unmarried women who were heads of their households and over 23 could also vote.

The next month, changes were made that allowed women with these same qualifications to run for political office. Because of this, some women ran for office and won seats in local governments as councilors and even mayors. This was a surprising move by Primo de Rivera. Many believed he did it to gain support for his government before upcoming elections. During this short time, many political parties tried to get women's votes before the elections were canceled.

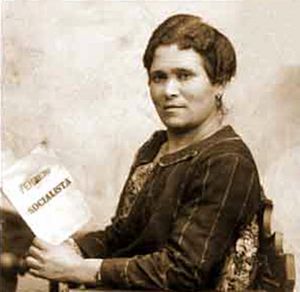

María Cambrils, a writer, was happy that women got the right to vote. However, she didn't like the limits placed on female voters. The leader of the Socialist Party (PSOE), Andrés Saborit, also supported women's voting rights. He believed that socialism needed to include women as important agents of change in society.

Some Catholic groups tried to use this new law for their own political gain. In some local elections, up to 40% of their votes came from women. However, by the time of the next national elections, the law giving women the right to vote was no longer in effect. A new constitution was being written. The discussions around the 1924 law were very important for later debates about women's voting rights in the Second Republic.

Women in Politics

When women did get involved in politics before the Second Republic, it was often spontaneous. Their actions were sometimes ignored by male political leaders, especially those on the left. Still, these protests showed that women were becoming more aware of the need to be active in society and politics to improve their lives.

Middle-class women in cities, who had more free time, started to ask for changes to improve their lives. They wanted things like easier divorce laws, better education, and equal pay. When politicians heard these demands, they often called them "women's issues." No big changes were made during Primo de Rivera's rule.

The Agrupación Femenina Socialista de Madrid (Socialist Women's Group of Madrid) was active during this time. To reach more people, they invited three women lawyers from Madrid – Victoria Kent, Clara Campoamor, and Matilde Huici – to speak at Casa del Pueblo in 1925 and 1926. They wanted to understand women's demands better. However, by March 19, 1926, Campoamor had stopped helping the Socialists with women's issues.

A writer named Margarita Nelken said in 1922 that she didn't think Socialists or Catholics offered much hope for women. She believed neither group truly understood the problems women faced. She saw this as a major weakness in the feminist movement during Primo de Rivera's time.

Socialist Women

Women in the Socialist Party

In the 1920s and early 1930s, more women became involved with socialist movements. However, this didn't mean they participated much in the political side. Socialist political groups were often unfriendly to women and didn't want them to get involved. When women did create socialist groups, they were usually helper groups for male-dominated ones. This was true for the Group of Feminist Socialists of Madrid. This was different from anarchist women, who played more active roles. Because of this, when the Civil War started, few socialist women went to the front lines.

| PSOE members of the Congress of Deputies | |||||

| Election | Seats | Vote | % | Status | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 |

7 / 409

|

Opposition | Pablo Iglesias Posse | ||

Later Years of the Dictatorship (1925-1930)

Primo de Rivera's government didn't have a real national congress until the Asamblea Nacional Consultiva was created in 1927. This group was made up of appointed members from different parts of Spain, but it had very little power. Only about 3% of the members in the last Asamblea Nacional Consultiva were women. Some of these women were wives of noblemen who didn't take their roles seriously. Others were chosen because of their contributions to culture and art. Their appointments showed a desire to see women become more involved in political life.

The Socialist Party (PSOE) and the UGT (a major labor union) argued internally about whether to join this assembly since it had little power. After much debate, both groups refused to participate. As a result, the government appointed socialists to the assembly without the party's or union's approval. María Cambrils was one of these socialist women who served in the 1927 Assembly.

Women's Political Roles

Women gained the chance to be part of national government during the 1927–1929 period. A law from September 12, 1927, stated that "men and women, single, widowed or married" could be part of the assembly. Married women needed their husbands' permission.

The 1927–1929 session also started to write a new Spanish constitution. Article 55 of this new constitution would have given women full voting rights. However, this article was not approved. Even so, women were allowed to serve in the National Assembly, and 15 women were appointed on October 10, 1927. Thirteen of them were "Representatives of National Life Activities," and two were "State Representatives." These women included María de Maeztu, Micaela Díaz Rabaneda, and Concepción Loring Heredia.

When the Congress of Deputies started its first session in 1927, the President of the Assembly specifically welcomed the new women. He said their past exclusion had been unfair. On November 23, 1927, Loring Heredia interrupted a minister to demand an explanation. This was the first time a woman had ever done this in the Congress.

Spain's right-wing political groups were divided into several parts, like those who supported the king (Alfonsine monarchists), traditionalists (Carlists), and fascists (Falangists). They also included parties like Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA). None of these groups had strong women's branches. Most of the political activity from right-leaning women came from Catholic women's groups. Their public actions sometimes made conservative groups nervous. This was because these women wanted to protect the traditional role of women at home, but they were also very visible as activists outside the home. In 1928, a major Catholic women's group had 119,000 members.

Women's Rights Discussions

The Feminine Socialist Group of Madrid met in 1926 to talk about women's rights. Victoria Kent and Clara Campoamor were among those who attended. The Agrupación Femenina Socialista de Madrid was also active. They invited the three women lawyers, Victoria Kent, Clara Campoamor, and Matilde Huici, to speak at Casa del Pueblo in 1925 and 1926. They wanted to understand what women needed. However, by March 19, 1926, Campoamor had stopped helping the Socialists with women's issues.

Margarita Nelken believed that neither Socialists nor Catholics truly offered hope for women. She felt they couldn't see the real problems women faced. She saw this as a major problem for the feminist movement during Primo de Rivera's time.

Work and Jobs for Women

In 1930, 40% of all working women in Spain had jobs in domestic roles, like housekeepers. This was the largest type of job for women. Even though Primo de Rivera had strong ideas about women's roles, women sometimes held important positions in the Spanish government.

Education for Girls and Women

Things slowly started to change for women's education. By 1930, 62% of women could read and write. In primary schools, the number of girls and boys was almost equal. However, this was not true for universities, where only 4.2% of students were women in 1928.

Before the Second Republic, the Socialist Party (PSOE) knew that women workers didn't have the same educational opportunities as men. But even with this knowledge, they didn't offer clear solutions or strongly support women's education. Their main demand for women's education was simply for equal education for everyone.

Women in Art

Women were also involved in the arts during this time. Maruja Mallo and Concha Méndez, who were painters, were part of an important group of artists called the Generation of 1927. They were active in Madrid and lived at the Students Residence, a place where many new and experimental artists lived in the 1920s and 1930s. Maruja Mallo, originally from Galicia, would go with Concha Mendez and other famous male painters to find inspiration for their art.

Daily Life for Women

In the years leading up to the Second Republic and during the dictatorship, women on the streets of big cities like Barcelona and Madrid often faced harassment.

More women started working outside the home during this period. They worked in universities and in service jobs. Women also began to enter places that were traditionally for men, like cafes and special clubs for learning and discussion. In the 1920s, some conservative men reacted negatively to these changes. They saw these women as confusing gender roles.

Many middle-class and upper-class women became feminists because of their boarding school education. Their parents couldn't always guide their political ideas. Sometimes, fathers encouraged their daughters to think politically. Other times, girls were taught in classes that were supposed to reinforce traditional gender roles, but this sometimes led to them breaking away from their families' ideas and becoming feminists. Families with left-leaning views were more likely to see their daughters become feminists through direct influence. Right-leaning families were more likely to see their daughters become feminists because strict gender rules caused them to break away from their families.

See also

In Spanish: Las mujeres durante la dictadura de Primo de Rivera para niños

In Spanish: Las mujeres durante la dictadura de Primo de Rivera para niños