Élie Lescot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Élie Lescot

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 29th President of Haiti | |

| In office May 15, 1941 – January 11, 1946 |

|

| Preceded by | Sténio Vincent |

| Succeeded by | Franck Lavaud (Chairman of the Military Executive Committee) |

| Minister of Interior | |

| In office September 20, 1933 – May 15, 1934 |

|

| President | Sténio Vincent |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Titus |

| Minister of Interior and Justice | |

| In office May 17, 1932 – September 20, 1933 |

|

| President | Sténio Vincent |

| Preceded by | Emmanuel Rampy |

| Succeeded by | Himself (Interior) Joseph Titus (Justice) |

| Minister of National Education, Agriculture and Labor | |

| In office January 27, 1930 – April 22, 1930 |

|

| President | Louis Borno |

| Preceded by | Hannibal Price IV |

| Succeeded by | Louis Edouard Rousseau |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Antoine Louis Léocardie Élie Lescot

December 9, 1883 Saint-Louis-du-Nord, Haiti |

| Died | October 20, 1974 (aged 90) Laboule, Haiti |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouses | Corinne Jean-Pierre, Georgina Saint-Aude (1892–1984) |

| Children | Andrée Lescot |

| Profession | Pharmacist |

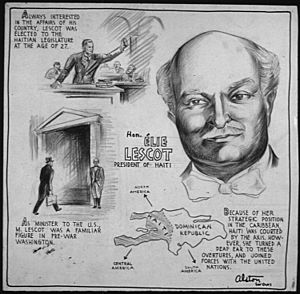

Élie Lescot (born December 9, 1883 – died October 20, 1974) was the President of Haiti. He served from May 15, 1941, to January 11, 1946. He came from a group of mixed-race families who were important in Haiti. During World War II, he used the global situation to keep his power. He also kept strong connections with the United States, Haiti's powerful neighbor. His time as president saw a difficult economy and strict rules against people who disagreed with him.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Élie Lescot was born in Saint-Louis-du-Nord, a town in Haiti. His family was middle-class and of mixed-race background. They were descendants of free people of color from the time Haiti was a colony. After finishing high school in Cap-Haïtien, he went to Port-au-Prince to study pharmacy. Later, he moved to Port-de-Paix and worked in the business of buying and selling goods.

In 1911, his first wife passed away. After this, Lescot decided to enter politics. Two years later, he was chosen to be a member of the Chamber of Deputies. He lived in France for four years during the time the United States occupied Haiti (1915-1934). When he returned, he worked in the governments of Louis Borno and Sténio Vincent. Four years later, he became the ambassador to the nearby Dominican Republic. There, he became friends with President Rafael Trujillo. He then moved to Washington, D.C. after being made ambassador to the United States.

Becoming President During Wartime

Lescot's strong political and economic ties to the United States helped him become president of Haiti. The U.S. government quietly supported his campaign to take over from Sténio Vincent in 1941. Some important members of the Chamber of Deputies did not want him to be president. They believed Haiti needed a black president from a majority African background.

It was said that Lescot used Trujillo's influence to help him win. He received 56 out of 58 votes from the lawmakers. Deputy Max Hudicourt claimed that Lescot won by using unfair methods against the lawmakers.

Lescot quickly took strong control of the government. He made himself the head of the Military Guard. He also appointed a small group of white and mixed-race people from the elite to important government jobs. This included his own sons. This made many of Haiti's mostly African people dislike him greatly.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Lescot declared war on the Axis Powers. He promised to fully support the Allied war effort. His government offered a safe place in Haiti for European Jewish refugees. This was done with the help of Trujillo. In 1942, Lescot said the war meant he had to stop the constitution. He then had the parliament give him unlimited power as president. People who were against him were watched closely and sometimes bothered by security forces.

Failed Rubber Program

During the war, an Axis blockade stopped rubber supplies from the East. Because of this, Lescot's government started a big project with the United States. The goal was to grow more rubber in the Haitian countryside for the war. The Export-Import Bank in Washington gave $5 million in 1941. This money was for growing rubber plants in Haiti. The project was called the Société Haïtiano-Américane de Développement Agricole (SHADA). An American plant expert named Thomas Fennell managed it.

SHADA started its work in 1941 with a lot of military support from the U.S. government. By 1943, about 47,177 acres (191 square kilometers) of land were cleared. This land was used to plant a vine called cryptostegia, which was thought to produce a lot of rubber. The program eventually took over 100,000 hectares of land. Farmers in northern Haiti were encouraged to stop growing food crops. Instead, they were told to grow rubber to meet the high demand.

Lescot strongly supported SHADA. He said the program would make Haitian farming more modern. The United States also promoted the project with a big public relations campaign. However, many farming families were forced to leave Haiti's best farming lands. In Jérémie, nearly a million fruit trees were cut down. Farmers' homes were entered or destroyed. Haiti's Minister of Agriculture, Maurice Dartigue, wrote to Fennell. He asked him to respect the Haitian people's feelings and their rights.

But the rubber plants did not produce as much as expected. Not enough rubber was made for significant exports. Dry weather also led to poor harvests.

A survey by the U.S. military concluded that SHADA was very expensive for American taxpayers. It also said the program was not respected by the Haitian people. The U.S. government offered $175,000 to the farmers who had lost their land. After this, they suggested stopping the program.

Lescot was worried that ending SHADA would cause more unemployment. At its peak, the program employed over 90,000 people. He feared it would also harm his public image and Haiti's struggling economy. He asked the Rubber Development Corporation to close the program slowly until the end of the war. But his request was turned down.

End of Presidency and Exile

Lescot's government was almost out of money. The economy was struggling. He asked the United States for more time to pay back Haiti's debts, but he was not successful. The relationship between Lescot and Trujillo in the Dominican Republic also broke down. In Haiti, Lescot made the Military Guard bigger. He put light-skinned officers in charge. A system of rural police chiefs, called chefs de section, ruled with force and fear. In 1944, some lower-ranking black soldiers were caught planning a rebellion. They faced severe punishment without a proper trial.

That same year, Lescot changed the law to extend his presidential term from five years to seven. By 1946, his attempts to control the news and stop opposition newspapers caused strong student protests. A revolt began in Port-au-Prince. Groups who wanted more power for black Haitians, Marxists, and popular leaders all joined together against him. Crowds protested outside the National Palace. Workers went on strike, and some government buildings were damaged. Lescot's government, mostly made of mixed-race people, was not liked by Haiti's mostly black military, the Garde.

Lescot tried to order the Military Guard to stop the protests, but they refused. Lescot and his government believed their lives were in danger. They fled Haiti and went into exile. A group of three military leaders took power in his place. They promised to hold new elections. Right after Lescot left, independent radio stations and newspapers became popular. Groups who had been silenced for a long time felt hopeful about Haiti's future. Dumarsais Estimé later became Haiti's president. He was the first black president of Haiti since the U.S. occupation ended.

See also

In Spanish: Elie Lescot para niños

In Spanish: Elie Lescot para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |