1797 Rugby School rebellion facts for kids

The 1797 Rugby School Rebellion was a big protest by students at Rugby School. It happened after the headmaster, Dr. Henry Ingles, told older students they had to pay for broken windows at a local shop. The students had smashed these windows themselves. During the protest, many school windows were broken, and furniture was burned. The boys then went to an island on the school grounds. A local official read a special law called the Riot Act. Soldiers then crossed the island's moat and captured the students.

This rebellion was not the only one at Rugby School. Many other public schools in England also had similar problems between 1710 and 1832.

Rugby School and Old School Rules

Rugby School started in 1567. It was one of the first seven public schools in England. Other famous schools like Winchester (1382) and Eton College (1440) were also part of this group.

Discipline was often very poor in public schools during the 1700s and 1800s. Experts Kenneth Sheard and Eric Dunning say this was because of how power was shared between students and teachers. Rich families used to teach their children at home with tutors. When these children went to school, they saw teachers as paid staff. They thought teachers were below them in social class. This made teachers unsure how to control students who came from powerful families.

When discipline was at its worst, students often rebelled. In 1710, students at Winchester protested about their beer. Winchester had more protests in 1770, 1774, 1788, and 1793. Eton students rebelled in 1728, 1768, and 1783. Harrow had a protest in 1771. Rugby's first protest happened in 1786.

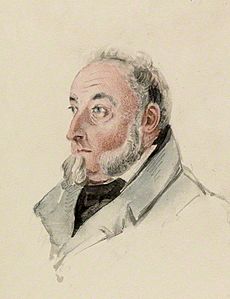

Dr. Henry Ingles was the headmaster of Rugby School during the 1797 rebellion. He became headmaster in 1794. He was known for being strict and serious. Students even called him the "Black Tiger."

The November 1797 Protest

In November 1797, Headmaster Ingles caught a student named Astley. Astley was shooting cork bullets at windows. He told Ingles he bought the gunpowder from a local shop called Rowell's. This shop sold groceries, books, and hardware.

Ingles went to Rowell, the shopkeeper. Rowell said he did not sell gunpowder. He showed Ingles his sales book, which said "tea" was sold. Ingles believed the shopkeeper over Astley. Astley was then flogged, which means he was whipped as punishment, for lying.

Astley told his friends why he was punished. His friends got angry and smashed the windows of Rowell's shop.

When Ingles heard about the broken windows, he made a rule. All students in the fifth and sixth forms had to pay for the damage. The boys wrote a special letter called a round robin. This letter hid who the leaders were. In it, they refused to pay. The headmaster then threatened to punish them.

That Friday, after the fourth lesson, the boys placed a small homemade bomb, called a petard, against a school door. The bomb blew the door off its hinges.

The next day, Saturday, the school bell was rung by the boys. This was a signal for the next part of their protest. Younger students, called fags, were sent to the boarding houses. They gathered other boys to the main school building.

The students broke all the windows of the main building. They threw the school's furniture, including its wooden wall panels, into the Close. The Close was a large field in front of the school. They set the furniture on fire. Dr. Ingles's books were also added to the fire. Billy Plus, the school's butler, saved some of the more expensive books. The boys also nailed shut the passage between School House and the main building. This stopped Ingles, who lived in School House, from getting into the school.

Saturday afternoons had no lessons, so many teachers had left the school. Ingles sent messages for them to come back. But most were too far away to be found. Some were fishing, and others were hunting.

Ingles sent a message to Mr. Butlin. He was a local banker and the town's justice of the peace. It was market day in Rugby, so Butlin asked horse-dealers to help with their long whips. He also asked an army recruitment group, led by a sergeant, for help.

An armed guard with a fixed bayonet was placed at School House. The rest of the soldiers, along with the horse-dealers and special police, went to the Close.

The protesting students left their bonfire. They went to "the Island." This was an old Bronze Age burial mound next to the Close. It was surrounded by a water moat that was up to 6 feet (1.8 m) deep and 20 to 30 feet (6 to 9 m) wide. After crossing the ditch, the boys pulled up the wooden drawbridge.

Mr. Butlin kept the boys busy by reading them the Riot Act. Meanwhile, the soldiers went around behind them. They crossed the moat on the other side and captured the students.

What Happened Next

Ingles had stayed locked in School House during the protest. He came out when it was over. He immediately expelled the main leaders of the rebellion. Many other students were flogged.

One of the leaders was later identified as Willoughby Cotton. He joined the army soon after. He later led troops in Jamaica in 1831 to deal with a local uprising. Of the students who were expelled, one later became a bishop, and another became a marquess.

The 1797 rebellion was not the last one at public schools. Rugby School itself had more student protests in 1820 and 1822. Between 1797 and 1832, there were ten more rebellions in schools. Four happened at Eton, three at Winchester, and one each at Charterhouse, Harrow, and Shrewsbury.

|

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |