1935 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition facts for kids

The 1935 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition was a quick trip to Mount Everest. It happened because Tibet unexpectedly gave permission for climbers to visit. This expedition was a practice run for a bigger climb planned for 1936.

After many arguments, Eric Shipton was chosen to lead the team. He was known for his successful, lightweight climbing style, like his trip to the Nanda Devi area in India in 1934.

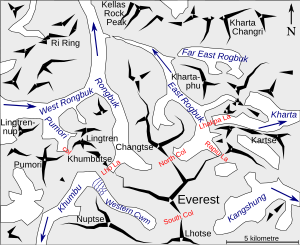

This expedition was smaller and cheaper than others. The climbers approached Everest from the north side. They planned to climb after the summer monsoon rains. However, the monsoon was very late that year. The bad weather and deep snow made it hard to reach the very top of Everest.

Even so, the team climbed many smaller peaks for the first time. They also found a possible new way to climb Everest from the south, through a place called the Western Cwm. This route could be used if Nepal ever allowed climbers into its territory.

This expedition greatly influenced future British climbs on Everest after World War II. Eric Shipton himself later led a trip in 1951 to explore the southern route.

Contents

Why They Went: The Background

British climbers had been trying to reach the top of Mount Everest since 1921. But no one had made it to the summit. These trips were planned by the Mount Everest Committee, a group from the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club.

After the 1933 expedition, climbers had reached a new high point. The committee felt they had done well. They asked Tibet for permission for another try and chose Hugh Ruttledge to lead again.

Some younger climbers were not happy with this. They felt the leader should be a strong climber, not someone focused on geography. Ruttledge, who was 50 and had a limp, offered to step down. The committee accepted, thinking there would be no expedition soon.

Then, in early 1935, the Tibetan government unexpectedly gave permission for expeditions in 1935 and 1936! The committee decided to send a quick "reconnaissance" (exploring) trip in 1935. There wasn't enough time or money for a full summit attempt that year.

Just to be polite, they offered the leadership to Ruttledge again. To their surprise, he said yes! This caused a big fuss. Many supported Colin Crawford for the leader instead. Ruttledge resigned a second time.

The committee struggled to find a leader. They offered the job to many people, but everyone said no. Finally, after more arguments, Eric Shipton was chosen to lead the 1935 trip.

Shipton and Tilman's Role

Eric Shipton had been on the 1933 Everest expedition. After that, he and Lawrence Wager explored a new route back to Sikkim. This made Shipton prefer lightweight, exploratory climbing over large, expensive expeditions.

The next year, Shipton and Bill Tilman led a small trip to Nanda Devi. They were the first to enter the Nanda Devi Sanctuary. They planned to return in 1935 to try to climb Nanda Devi.

In February 1935, Shipton spoke about Nanda Devi. He got a great reaction from the audience. One thing really interested the Everest Committee: his entire Nanda Devi trip had only cost £287!

Because Tibet gave unexpected permission, the Mount Everest Committee planned a summit attempt for 1936. But first, they wanted a reconnaissance trip in 1935. They decided to use Shipton's lightweight style for the 1935 Everest trip. This trip could be set up quickly and paid for with existing money. This saved new funds for the 1936 summit attempt.

Shipton was offered the leadership for 1935. He wouldn't arrive until July, which was after the monsoon was expected to start. But this would let the team see if the monsoon snow had settled.

Getting Ready for the Expedition

The expedition had a few goals. They wanted to test climbing conditions during and after the monsoon. They also wanted to see which climbers might be good for the 1936 trip. And they planned to continue the exploration work from the 1921 expedition.

It was clear: no one was to try for the summit. They also decided not to use extra oxygen. Bill Tilman was sad to miss the Nanda Devi summit attempt. But Shipton convinced him by explaining the lightweight, exploring nature of the Everest trip.

The team included Charles Warren and Edmund Wigram (both doctors), Edwin Kempson (a mathematician), and Dan Bryant (an ice climber from New Zealand). Shipton thought this was enough. But then Michael Spender, a surveyor, was added to the team. Spender had been unpopular on past trips. But Shipton and Spender became good friends.

Shipton didn't like the fancy lifestyle of earlier British expeditions. He wanted to save money. He consulted a food expert to plan a simple, healthy diet. It included lentils, dried vegetables, and powdered milk. They also took cod liver oil and vitamin tablets. This was very different from the caviar and lobster served in 1933! Shipton later admitted his diet was perhaps "too far the other way."

The team met in Darjeeling, India, on May 21, 1935. With help from Karma Paul, who had been on all Everest trips since 1922, they hired fourteen Sherpas. Shipton wanted a couple more. A 19-year-old was chosen. He had no climbing experience but was picked because of his "attractive grin." This young man was Tenzing Norgay.

The group traveled north through Sikkim into Tibet. Then they went west towards Everest. They took a route through Sar, which was closer to Nepal than earlier trips. They split into three groups to explore near the Nyonno Ri (28°12′18″N 87°36′30″E / 28.2050°N 87.6082°E) and Ama Drime (28°05′05″N 87°36′24″E / 28.0847°N 87.6067°E) mountains.

However, this was against the rules in their passports. They were ordered back to the main road through Gyankar Nangpar. From Nyonno Ri, they had a clear view of Everest in good weather. Some wondered if they could have rushed to the summit then. But Shipton didn't try, as it was forbidden by his passport and the expedition's goal. They reached Rongbuk Monastery on July 4.

Climbing the North Col

Spender stayed to map the North Face. The rest of the team climbed the East Rongbuk Glacier. They reached the base of the North Col on July 8. This was good timing, even though many felt sick. Bryant was especially ill, losing 14 pounds in three days. He went back down to Rongbuk.

As they moved Camp III higher, they found the body of Maurice Wilson. He was an unusual British climber who had died in 1934 trying to climb Everest alone. They set up camp next to food left from 1933. They were happy to add plums and chocolate to their simple diet.

The old path up to the North Col was blocked by snow. So, they took a new path to the right. They reached the 23,030-foot Col on their second try on July 12. But from there, heavy monsoon snow made climbing impossible.

On July 16, they started to descend from the Col. They found a huge avalanche had swept away snow about 6 feet deep. This showed how dangerous their climb had been. They reached Camp III safely. But they decided it was too risky to try the Col again. While this happened, Spender was surveying. Wigram and Tilman climbed the Lhakpa La and two peaks next to it.

Climbing Many Peaks

The expedition focused on climbing many smaller peaks. Two teams separately climbed the 23,640-foot Khartaphu. Then Kempson and Warren climbed the 23,070-foot Kharta Changri and two other nearby peaks. Spender mapped that area. Shipton, Wigram, and Tilman climbed the 23,190-foot Kellas Rock Peak and three more mountains. All the peaks they climbed were over 21,000 feet high.

Kempson had to go home. The rest of the team split into three pairs. Spender and Warren continued their mapping. Shipton and Bryant went to the West Rongbuk Glacier. They made first climbs of Lingtren and its nearby peaks, and Lingtrennup.

Looking down into the Western Cwm in Nepal, Shipton thought this could be a good route for a southern attempt on Everest. Tilman and Wigram went up the main Rongbuk Glacier to Lho La. From there, they decided the West Ridge was not a way to the summit. They also saw no way down to the Western Cwm from Lho La.

Everyone met back at Rongbuk on August 14. From there, they all tried to climb the 24,730-foot Changtse. But they had to stop at 23,000 feet because of deep snow. They had waited to try Changtse to see how high-altitude snow behaved during the monsoon.

Returning to Rongbuk, they hiked across the country to the Kharta valley. They hoped to explore Nyonno Ri again, but the authorities said no. Near the border of Tibet and Sikkim, they climbed in the Dodang Nyima range. Then they returned to Darjeeling.

Seeing the Western Cwm and Solu Khumbu

In 1921, George Mallory and Guy Bullock reached a pass between Pumori and Lingtren. Mallory looked down at the Western Cwm and said it looked "terribly steep and broken." He was glad they didn't have to go up it.

Shipton and Bryant reached the same spot on August 9, 1935. But mist blocked their view for hours. They returned to the pass on August 11. This time, the mist cleared after many hours. They were able to take the first photo of the Khumbu Icefall leading up to the Western Cwm.

Bryant wrote that a ridge from Nuptse squeezed the glacier into a narrow lip. Over this lip, the ice poured down in a "gigantic ice-fall." He said the cwm itself must be amazing, completely surrounded by mountains over 25,000 feet high.

Shipton said the Sherpas got excited because they recognized landmarks in their homeland, the Solu Khumbu. He felt the route up the icefall and cwm "did not look impossible." He hoped to explore it someday.

What They Achieved and Its Impact

The expedition successfully climbed 26 peaks over 20,000 feet. This was as many as all previous climbing trips combined! Of these, 24 were climbed for the very first time.

In 1994, Warren remembered, "This surely must have been one of the most enjoyable of all the expeditions to Mount Everest. It was small and achieved the objectives set for it at little cost." By these measures, and the mapping results, the expedition was a success. But it didn't get much attention from the news or public. It was the only pre-war British expedition that didn't publish a book about it.

The expedition's experiences led to some wrong ideas. The monsoon conditions had been bad, making climbing above 23,000 feet impossible. They didn't realize that the 1935 monsoon was unusually late. At that time, no one really understood when the monsoon would start.

The planned 1936 expedition, meant for before the monsoon, was ruined by a very early monsoon that year. This led to no more post-monsoon attempts on Everest until a Swiss expedition in 1952. It was slowly discovered that the time after the monsoon can actually be good for climbing.

The lightweight approach itself wasn't seen as a clear success. Everest expeditions, especially British ones, went back to large, military-style trips. This continued into the 1970s. Tilman and Bryant had struggled above 23,000 feet. So, they were not chosen for the 1936 trip. People didn't understand then that a climber's ability to get used to high altitude can change a lot from year to year.

Tilman proved this point. In 1936, he and Noel Odell made the first climb of the 25,645-foot Nanda Devi. This was the highest mountain climbed until Annapurna in 1950.

The 1935 expedition also had an unexpected impact on the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition, which was the first time the summit was reached. Tenzing Norgay had been impressive in 1935. In later years, he was a Sherpa on Everest many times. He was on all the later British expeditions, including 1936 and 1938. This led to him reaching the summit of Everest in 1953.

In 1935, New Zealander Dan Bryant hadn't done well at high altitude. But he was very popular and respected by the team. When Shipton was putting together his team for the 1951 Everest reconnaissance, he got an application from an unknown New Zealander. At that time, British climbers were usually preferred. But with happy memories of Bryant, Shipton decided to pick the New Zealander. He later wrote, "My momentary caprice was to have far reaching results." After his success in 1951, Ed Hillary was invited back to Everest in 1953.