1970 British Annapurna South Face expedition facts for kids

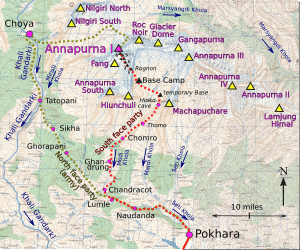

The 1970 British Annapurna South Face expedition was a daring climb in the Himalaya mountains. It was the first time climbers tried a super difficult route up the side of an 8,000-meter mountain. On May 27, 1970, climbers Don Whillans and Dougal Haston reached the top of Annapurna I. This mountain is 26,545 feet (8,091 m) high and is the tallest peak in the Annapurna Massif in Nepal.

Chris Bonington led the team. They started their climb from the Annapurna Sanctuary. They used special rock climbing skills to put up ropes on the very steep South Face. The team had planned to use extra oxygen. But they couldn't carry the oxygen tanks high enough for the main climbers to use when they went for the summit.

Sadly, on May 30, as the team was getting ready to leave, Ian Clough was killed by a falling block of ice called a serac. Many members of the expedition became famous in Britain. The climb was recognized around the world because it was so new and incredibly hard.

Contents

What is Annapurna?

The Annapurna Massif is a group of mountains in Nepal. For over 100 years, the rulers of Nepal didn't let explorers into the country. But in 1950, Nepal allowed the 1950 French Annapurna expedition to try climbing Annapurna I. This team, led by Maurice Herzog, successfully climbed the North Face. For most big mountains, the easiest way to the top is along a ridge. But for Annapurna, the North Face was the easiest path. Even though Annapurna was the first 8,000-meter mountain ever climbed, it's still very dangerous. Many climbers who try to reach its summit do not make it.

A New Way to Climb Big Mountains

After World War II, British rock climbing became very popular. New climbing clubs started in England and Scotland. Climbers became very competitive. People like Hamish MacInnes, Dougal Haston, and Chris Bonington were part of this new wave.

In 1960, Bonington climbed Annapurna II, which is 26,039-foot (7,937 m) high. It's about 20 miles (32 km) east of Annapurna I. That climb didn't involve rock climbing.

In 1963, an American team climbed Mount Everest using a very difficult route. Two years later, Bonington learned a new climbing method called "big wall" climbing. This involves climbing straight up a rock face using fixed ropes and special tools called jumars. This technique was used on the North Face of the Eiger in Europe. This new method opened up possibilities for more challenging climbs.

By 1964, all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks had been climbed. Bonington wanted to try something new: using rock climbing skills on these huge mountains. He got the idea to climb Annapurna's South Face. He knew it would be a "siege" climb, meaning it would take many weeks. No one had ever tried rock climbing at such high altitudes before. The South Face was almost twice as tall as the 6,000 feet (1,800 m) Eigerwand. Even above the main rock part, there were another 3,000 feet (910 m) to the summit.

Planning the Annapurna Expedition

The Mount Everest Foundation helped pay for the expedition. Bonington gathered a team of his friends. These included Nick Estcourt, Martin Boysen, Ian Clough, Mike Thompson, Mick Burke, and Haston. They also added Tom Frost, an American climber with lots of "big wall" experience. Frost was known and respected by Haston and Don Whillans. Only Bonington, Clough, and Frost had been to the Himalaya before. Kelvin Kent was the base camp manager, and David Lambert was the doctor. A four-person TV crew from ITN and Thames Television also joined them.

They brought 18,000 feet (5,500 m) of rope to fix on the mountain. They also had 40 oxygen cylinders and six breathing sets. The main gear was sent by sea. The team planned to use extra oxygen above 22,500 feet (6,900 m). But they hardly used it for climbing, and not at all above Camp VI. They did use it for climbers who got sick.

The Journey to Base Camp

In March 1970, the team flew to Kathmandu and then to Pokhara. They then walked to the Annapurna area. By 1970, the path was well known. The Sherpas, who are local mountain guides, were also more experienced. Pasang Kami, the sirdar (head Sherpa), treated the climbers as equals. Other Sherpas included Pemba Tharkay, Ang Pema, Mingma Tsering, Nima Tsering, and Kancha. Another British Army team helped Bonington by flying in 1,500 pounds (680 kg) of gear for him.

On March 16, Whillans, Thompson, and two Sherpas went ahead. They wanted to find a good spot for base camp. They found a temporary spot at the entrance to the Annapurna Sanctuary. This was where a 1957 expedition had set up camp.

Bonington and Whillans met on March 27. Whillans said he thought he saw a yeti and photographed its footprints! More importantly, he found a climbing route up the South Face. On March 29, the whole team gathered at the temporary base camp. An advance group, including Whillans, Haston, and Burke, set up the final base camp at 14,000 feet (4,300 m). This was three miles from the bottom of the mountain face. The monsoon season was expected around the end of May.

The Climbing Route

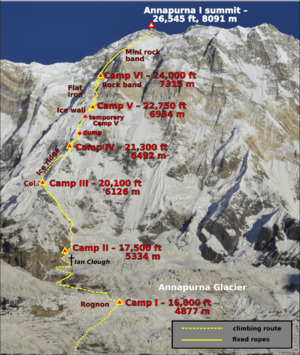

The climb from Camp III (at 20,100 feet (6,100 m)) to the top of the Rock Band (at 24,750 feet (7,540 m)) was very steep, with an average slope of 55 degrees.

| Main Camps on the Mountain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Height | Set Up | Details | |

| feet | meters | |||

| Temporary Base | 12,000 | 3,700 | March 28 | At the 1957 Machapuchare expedition's base camp |

| Base | 14,000 | 4,300 | March 31 | Next to the Annapurna glacier |

| Camp I | 16,000 | 4,900 | April 2 | On a rock island in the glacier |

| Camp II | 17,500 | 5,300 | April 6 | Under a rock overhang |

| Camp III | 20,100 | 6,100 | April 13 | A large, flat, safe area |

| Camp IV | 21,300 | 6,500 | April 23 | On a 30-degree sloping Ice Ridge |

| dump | 21,650 | 6,600 | May 11 | At the top of the Ice Ridge |

| temporary Camp V |

22,500 |

6,900 | May 6 | At the bottom of the Ice Wall, risky from snow |

| Camp V | 22,750 | 6,930 | May 9 | At the bottom of the Rock Band |

| Camp VI | 24,000 | 7,300 | May 19 | A tiny platform carved in snow |

| Summit | 26,545 | 8,091 | May 27 | |

Climbing Higher: The Ice Ridge and Rock Band

Whillans and Haston found a difficult path across the glacier to Camp I. This camp was on a rock island, far enough away from avalanches. They then found a spot for Camp II, which was under a rock overhang. Part of the route was under a dangerous ice overhang they called the "Sword of Damocles." They decided to move quickly under it to reduce risk.

On April 11, Boysen and Estcourt set up Camp III. It was a spacious and safe spot. They used special "Whillans Box tents," which were strong and cube-shaped.

Bonington and Frost tried to find a route up the Ice Ridge above Camp III. It was much harder than they thought. The snow was too soft to place anchors. They realized they would need to fix ropes all the way up the ridge. They changed their climbing method. They started using their 9-millimetre (0.35 in) fixed ropes, securing them with pitons (metal spikes) and karabiners (metal clips).

Whillans and Haston found a better way around the ridge, avoiding the soft snow. All four climbers then used this new path. It was still risky due to avalanches. They had to climb a small ridge to avoid a dangerous gully.

By April 18, they had only gained 1,000 feet (300 m) in eleven days. On April 19, Haston found a way through huge snow overhangs to reach the main ridge. Two days later, he found a perfect spot for Camp IV.

Unexpectedly, four trekkers, whom the Sherpas called "London Sherpas," arrived at Base Camp. They helped carry loads up to Camp IV. Other trekkers also came to watch and help.

Boysen and Estcourt worked on the upper part of the Ice Ridge above Camp IV. It was very narrow. Boysen even had to crawl through a 20-foot (6.1 m) tunnel in the ice! He then had to climb a difficult ice cliff. This was the hardest ice climb Boysen had ever done. They spent a whole day climbing only 300 feet (91 m). The next day, they found an ice-covered rock wall that led upwards.

Bonington and Clough took over the climbing. They sometimes moved only 10 feet (3.0 m) in an hour. Whillans suggested that Sherpas carry supplies up to Camp III. This way, climbers could rest at Camp III instead of going all the way to Base Camp.

On May 3, Whillans, Frost, and Burke carried a tent up to Camp IV. Bonington and Haston reached a col (a low point on a ridge) at 21,650 feet (6,600 m). The Ice Ridge ended here, and a snow slope led to the Ice Wall. The next day, they carried ropes to the col. Haston ran out 500 feet (150 m) of rope towards the Ice Wall. At 22,350 feet (6,810 m), the slope became vertical. This was where they planned Camp V. It was hard to get supplies up to this height. It took at least five days for anything to arrive from base camp.

Whillans and Haston set up Camp V. But snow buried their tent that night. So they looked for a better spot. They found a sheltered area under a snow overhang at the foot of the Rock Band. On May 9, Frost and Burke set up the new Camp V at this higher location.

Frost and Burke started climbing the Rock Band, which was about 50 degrees steep. They aimed for a feature called the "Flat Iron." Good weather helped, but melting ice caused rocks to fall. There were shortages of rope, oxygen, tents, food, and fuel at Camp V. On May 12, Burke and Frost made more progress, but it was risky. A storm hit them when they turned back for the day. Luckily, fresh supplies arrived.

Bonington had planned for climbing pairs to take turns resting, carrying supplies, and extending the route. Sherpas carried supplies higher than expected. Other trekkers also helped. On May 13, Bonington decided Whillans and Haston would replace Frost and Burke. There was some disagreement among the climbers, but they worked it out.

On their last day leading, Burke and Frost fixed ropes all the way to the Flat Iron. Bonington thought Burke's climb was the hardest rock climbing of the whole expedition.

On May 17, Boysen, Whillans, and Haston carried gear to the top of the Flat Iron. This was a good spot for Camp VI. Boysen had to go back to camp to rest. Whillans and Haston found a place for Camp VI. That night, an avalanche of snow crushed their tent at Camp V. Haston's backpack, with his personal gear and food, fell down the mountain. Whillans was left alone at Camp VI with no food. Bonington climbed up to help support the lead team. The climb to Camp VI was very tiring. There was very little food or rope at Camp VI.

On May 20, Haston returned to Camp VI. Whillans had been without food for over 24 hours. Bonington brought more food and a radio. Camp VI was a terrible place. The tent was too big for the ledge, and the wind was severe. The same day, the lead climbers climbed 400 feet (120 m) from Camp VI. But they ran out of food and rope. They had no tent for Camp VII, which they wanted to place at the top of the Rock Band. They heard that the army team on the other side of the mountain had reached the summit.

On May 22, Bonington and Estcourt headed up with supplies and oxygen. But Estcourt had to turn back. Haston and Whillans reached the top of the "mini rock band" at the top of the Rock Band. They had no rope left, so they climbed without protection. They estimated they had only 1,500 feet (460 m) left to the summit. They reached the 25,000-foot (7,600 m) snowfield above the Rock Band. But they had no tent or food. The next day, Bonington carried a tent, a camera, and food from Camp V to VI. He had to leave his own gear behind.

On May 24, in terrible weather, Bonington and Clough managed to carry supplies to Camp VI. But they found Haston and Whillans had been forced back there. All four climbers had to spend the night together in a two-person tent.

Reaching the Summit

For the next two days, the entire mountain was covered in snow. It seemed the monsoon season had arrived. But on May 27, at Camp VI, the weather improved. Whillans and Haston left Camp VI around 7:00 AM. They had no extra oxygen. They reached the snowfield at 11:00 AM. They could see the summit through breaks in the clouds. They decided to move the tent higher, but they had a bigger goal for the day. They had no food or sleeping bags.

They faced an ice plateau, then a snow ridge, and then an 800-foot (240 m) cliff of ice and rock leading to the top. They left the tent at the bottom of the ridge and climbed without safety ropes. Neither climber had trouble breathing.

The last 50 feet (15 m) of the ice cliff was straight up. But there were good places to hold on. As they reached the north side of the mountain, the wind stopped. They saw footprints from the army team. Haston filmed Whillans reaching the summit, then they switched places. They reached the top at 2:30 PM and stayed for about 10 minutes. They could see the other two Annapurna summits. They had 150 feet (46 m) of rope left. By 5:00 PM, they had made the difficult climb back down to Camp VI.

Lower down the mountain, everyone was stuck in the storm. Bonington, at Camp IV, made his regular radio call. He asked Haston if they had been able to get out of their camp. Because of static, he didn't hear Haston's reply: "Aye, we've just climbed Annapurna." But Base Camp heard it loud and clear! The news quickly spread up the mountain.

Leaving the Mountain

Burke and Frost wanted to try for the summit too. Bonington agreed, as long as they also helped clear the camps. So on May 28, Burke and Frost reached Camp III. Whillans and Haston climbed down. By evening, Frost and Burke reached Camp VI. On May 29, they made their attempt. But Burke had to turn back. Frost reached the snowfield, stayed there for almost three hours, but then turned back because of fierce wind.

On May 30, the team was clearing the mountain. Most of the group reached Base Camp. Then Thompson rushed down, calling out in sadness. He and Clough had been passing under the "Sword of Damocles" when a block of ice fell. This caused an avalanche that killed Clough. His body was carried to base camp. He was buried at the foot of a rock face where he had taught the Sherpas and TV crew how to use climbing tools. As they walked down the valley, they saw that the snow had melted, and flowers were blooming.

What Happened Next?

This expedition was a huge success for British mountaineering. It was seen as a major step forward in climbing. It showed a new way of climbing big mountains: choosing harder, more direct routes instead of the easiest ones.

For the first time in Britain, people could watch the climb on TV as it happened. Interviews with climbers and film from the climb were shown on News at Ten every week. Film from the summit was shown only five days after it was taken! A one-hour documentary was later shown on Thames Television.

Bonington went on to lead more expeditions. The Everest Southwest Face expedition of 1975 was a direct follow-up. Haston was among those who reached the summit on that climb. Sadly, Burke died during that expedition. Whillans was not invited on more of Bonington's expeditions. Haston died skiing in the Swiss Alps in 1977. Estcourt was killed in 1978 on K2 during another Bonington expedition. By 1984, Pasang Kami, the sirdar, owned a fancy hotel in Kathmandu.

On October 8-9, 2013, Ueli Steck climbed the South Face alone. He reached Annapurna's summit without ropes or a support team. He completed the climb from base camp and the descent in just 28 hours.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |