Eight-thousander facts for kids

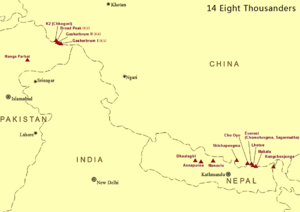

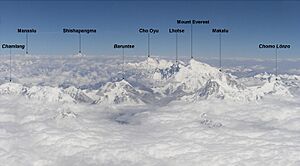

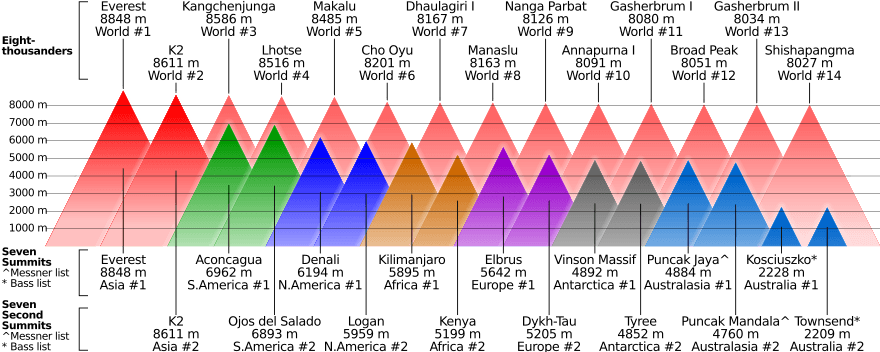

The eight-thousanders are 14 amazing mountains that are super tall. They are all over 8,000 meters (about 26,247 feet) high! The International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA) officially recognizes these peaks. They are also far enough away from other mountains to be counted as separate peaks.

All these giant mountains are found in Asia. They are in the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges. The very top parts of these mountains are called the "death zone". This means there isn't enough oxygen for people to breathe normally.

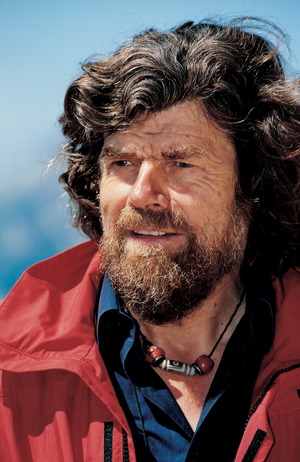

Many brave climbers dream of reaching the top of all 14 eight-thousanders. The first person to do this was Reinhold Messner from Italy in 1986. He did it without extra oxygen! Later, in 2010, Edurne Pasaban from Spain became the first woman to climb all 14. She used extra oxygen to help her. Then, in 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner from Austria became the first woman to climb all 14 without any extra oxygen. That's super impressive!

It took many years for climbers to reach the top of all 14 eight-thousanders for the first time. This happened between 1950 and 1964. But climbing them in winter is even harder! It wasn't until January 2021 that all 14 peaks had been climbed in winter. This last winter climb was on K2 by a team from Nepal.

A climber from Nepal named Nirmal Purja set a new record in 2019. He climbed all 14 eight-thousanders in an amazing 6 months and 6 days!

Contents

Climbing History

The first time someone tried to climb an eight-thousander was in 1895. Albert F. Mummery and his team tried to climb Nanga Parbat in Pakistan. Sadly, Mummery and two helpers, Ragobir Thapa and Goman Singh, died in an avalanche.

The first successful climb of an eight-thousander happened on June 3, 1950. French climbers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal reached the top of Annapurna.

Climbing in winter is much tougher. The first winter climb of an eight-thousander was on Mount Everest. A Polish team led by Andrzej Zawada made this happen. Two climbers, Leszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielicki, reached the top on February 17, 1980.

Reinhold Messner was the first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders. He finished this amazing feat on October 16, 1986. He did it without using extra oxygen. This was a huge achievement! Nine years later, in 1995, Erhard Loretan from Switzerland also climbed all 14 without extra oxygen.

The person who has climbed eight-thousanders the most times is Phurba Tashi from Nepal. He has reached the top 30 times between 1998 and 2011. Juanito Oiarzabal from Spain is second with 25 climbs.

Simone Moro from Italy has made the most first winter climbs of eight-thousanders, with four. Jerzy Kukuczka also made four winter climbs. The last eight-thousander to be climbed in winter was K2. A team of 10 Nepalese climbers, led by Nirmal Purja, reached its summit on January 16, 2021.

In 2010, Edurne Pasaban became the first woman to climb all 14 eight-thousanders. Then, in August 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner from Austria became the first woman to do it without extra oxygen.

The first husband and wife team to climb all 14 together were Nives Meroi and her husband Romano Benet from Italy. They finished in 2017. Nives Meroi was also the second woman to climb all 14 without extra oxygen. They climbed in a special way called "alpine style." This means they climbed without fixed ropes or extra oxygen.

As of November 2018, Italy has the most climbers who have completed all 14 peaks, with seven. Spain is next with six, and South Korea has five. Kazakhstan and Poland each have three climbers who have finished this "Crown of the Himalaya."

On October 29, 2019, Nirmal Purja from Nepal set a new speed record. He climbed all 14 eight-thousanders in just 6 months and 6 days! This was much faster than the old record, which was almost 8 years.

List of 14 Eight-Thousanders

Here is a list of the 14 eight-thousanders with some interesting facts about them.

| Mountain | First Climb | First Winter Climb | From 1950 to March 2012 | Climber Death Rate |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Height | Prominence | Isolation | Location | Date | Climber(s) | Date | Climber(s) | Total Ascents | Total Deaths | Deaths / Ascents | |

| Everest | 8848 m (29,029 ft) | 8848 m (29,029 ft) | undefined or infinite | 29 May 1953 | 17 February 1980 |

5656 | 223 | 3.9% | 1.52% | |||

| K2 | 8611 m (28,251 ft) | 4020 m (13,189 ft) | 1315.6 km (817.5 mi) | 31 July 1954 | on Italian expedition |

16 January

2021 |

|

306 | 81 | 26.5% | – | |

| Kangchenjunga | 8586 m (28,169 ft) | 3922 m (12,867 ft) | 124.2 km (77.2 mi) | 25 May 1955 | on British expedition |

11 January 1986 | 283 | 40 | 14.1% | 3.00% | ||

| Lhotse | 8516 m (27,940 ft) | 610 m (2,001 ft) | 2.4 km (1.5 mi) | 18 May 1956 | 31 December 1988 | 461 | 13 | 2.8% | 1.03% | |||

| Makalu | 8485 m (27,838 ft) | 2378 m (7,802 ft) | 17.2 km (10.7 mi) | 15 May 1955 | on French expedition |

9 February 2009 | 361 | 31 | 8.6% | 1.63% | ||

| Cho Oyu | 8188 m (26,864 ft) | 2344 m (7,690 ft) | 27.7 km (17.2 mi) | 19 October 1954 | 12 February 1985 | 3138 | 44 | 1.4% | 0.64% | |||

| Dhaulagiri I | 8167 m (26,795 ft) | 3357 m (11,014 ft) | 317.4 km (197.2 mi) | 13 May 1960 | 21 January 1985 | 448 | 69 | 15.4% | 2.94% | |||

| Manaslu | 8163 m (26,781 ft) | 3092 m (10,144 ft) | 105.5 km (65.6 mi) | 9 May 1956 | 12 January 1984 | 661 | 65 | 9.8% | 2.77% | |||

| Nanga Parbat | 8125 m (26,657 ft) | 4608 m (15,118 ft) | 187.9 km (116.8 mi) | 3 July 1953 | on German–Austrian expedition |

26 February 2016 | 335 | 68 | 20.3% | – | ||

| Annapurna I | 8091 m (26,545 ft) | 2984 m (9,790 ft) | 33.7 km (20.9 mi) | 3 June 1950 | on French expedition |

3 February 1987 | 191 | 61 | 31.9% | 4.05% | ||

| Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak) |

8080 m (26,509 ft) | 2155 m (7,070 ft) | 23.4 km (14.5 mi) | 5 July 1958 | 9 March 2012 | 334 | 29 | 8.7% | – | |||

| Broad Peak | 8051 m (26,414 ft) | 1701 m (5,581 ft) | 8.6 km (5.3 mi) | 9 June 1957 | 5 March 2013 | 404 | 21 | 5.2% | – | |||

| Gasherbrum II | 8034 m (26,358 ft) | 1524 m (5,000 ft) | 5.3 km (3.3 mi) | 7 July 1956 | 2 February 2011 | 930 | 21 | 2.3% | – | |||

| Shishapangma | 8027 m (26,335 ft) | 2897 m (9,505 ft) | 90.8 km (56.4 mi) | 2 May 1964 | 14 January 2005 | 302 | 25 | 8.3% | ||||

Could There Be More Eight-Thousanders?

In 2012, there were so many climbers on Mount Everest that it became crowded. To help with this, the government of Nepal thought about opening up other tall peaks for climbing. They asked the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) to consider adding five more peaks to the list of eight-thousanders. These peaks are part of Lhotse and Kanchenjunga. Pakistan also asked for one more peak on Broad Peak to be added.

The UIAA started a project called the AGURA Project to look into these ideas. These six new peaks are actually smaller tops of the existing eight-thousanders. But they are also over 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) tall. They also stick out enough from the main mountain to be considered. This "sticking out" is called topographic prominence. For these new peaks, they need to have a prominence of at least 60 meters (197 feet).

These peaks were suggested to the UIAA in 2012 to be counted as new eight-thousanders.

| Proposed new eight-thousander | Height (m) |

Prominence (m) |

Dominance (Prom / Height) |

Dominance classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Peak Central | 8011 | 181 | 2,26 | B2 |

| Kangchenjunga W-Peak (Yalung Kang) | 8505 | 135 | 1,59 | C1 |

| Kangchenjunga S-Peak | 8476 | 116 | 1,37 | C2 |

| Kangchenjunga C-Peak | 8473 | 63 | 0,74 | C2 |

| Lhotse C-Peak I | 8410 | 65 | 0,77 | C2 |

| Lhotse Shar | 8382 | 72 | 0,86 | C2 |

| K 2 SW-Peak | 8580 | 30 | 0,35 | D1 |

| Lhotse C-Peak II | 8372 | 37 | 0,44 | D1 |

| Everest W-Peak | 8296 | 30 | 0,36 | D1 |

| Yalung Kang Shoulder | 8200 | 40 | 0,49 | D1 |

| Kangchenjunga SE-Peak | 8150 | 30 | 0,37 | D1 |

| K 2 P. 8134 (SW-Ridge) | 8134 | 35 | 0,43 | D1 |

| Annapurna C-Peak | 8013 | 49 | 0,61 | D1 |

| Nanga Parbat S-Peak | 8042 | 30 | 0,37 | D1 |

| Annapurna E-Peak | 7986 | 65 | 0,81 | C2 |

| Shisha Pangma C-Peak | 8008 | 30 | 0,37 | D1 |

| Everest NE-Shoulder | 8423 | 19 | 0,23 | D2 |

| Everest NE-Pinnacle III | 8383 | 13 | 0,16 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle III | 8327 | 10 | 0,12 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle II | 8307 | 12 | 0,14 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle I | 8290 | 10 | 0,12 | D2 |

| Everest NE-Pinnacle II | 8282 | 25 | 0,30 | D2 |

These new peaks don't meet the UIAA's usual rule for major mountains. That rule says a mountain needs to rise at least 600 meters (1,969 feet) from the lowest point connecting it to a higher mountain. The lowest prominence of the current 14 eight-thousanders is Lhotse, at 610 meters (2,001 feet). However, the UIAA once used a smaller prominence rule (30 meters) for 4,000-meter peaks in the Alps. So, they thought 60 meters might be fair for 8,000-meter peaks.

As of November 2018, the UIAA has not made a final decision. It seems these ideas have been put aside for now.

Climbers of All 14 Eight-Thousanders

It can be tricky to confirm every climb in the Himalayas. But a special book called The Himalayan Database by Elizabeth Hawley is very important. It's used as a main source for climbs in the Nepalese Himalayas. Other websites also use her information.

Verified Climbs

First man to climb all 14 eight-thousanders, and first without extra oxygen First woman to climb all 14 eight-thousanders (with extra oxygen) First woman to climb all 14 eight-thousanders (no extra oxygen) Fastest climb of all 14 eight-thousanders Youngest person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders First disabled person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders

The "No O2" column shows climbers who did not use extra oxygen.

| Order | Order (No O2) |

Name | Years Climbed | Born | Age | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Reinhold Messner | 1972–1986 | 1944 | 42 | |

| 2 | Jerzy Kukuczka | 1979–1987 | 1948 | 39 | ||

| 3 | 2 | Erhard Loretan | 1982–1995 | 1959 | 36 | |

| 4 | Carlos Carsolio | 1985–1996 | 1962 | 33 | ||

| 5 | Krzysztof Wielicki | 1980–1996 | 1950 | 46 | ||

| 6 | 3 | Juanito Oiarzabal | 1985–1999 | 1956 | 43 | |

| 7 | Sergio Martini | 1983–2000 | 1949 | 51 | ||

| 8 | Park Young-seok | 1993–2001 | 1963 | 38 | ||

| 9 | Um Hong-gil | 1988–2001 | 1960 | 40 | ||

| 10 | 4 | Alberto Iñurrategi | 1991–2002 | 1968 | 33 | |

| 11 | Han Wang-yong | 1994–2003 | 1966 | 37 | ||

| 12 | 5 | Ed Viesturs | 1989–2005 | 1959 | 46 | |

| 13 | 6 | Silvio Mondinelli | 1993–2007 | 1958 | 49 | |

| 14 | 7 | Ivan Vallejo | 1997–2008 | 1959 | 49 | |

| 15 | 8 | Denis Urubko | 2000–2009 | 1973 | 35 | |

| 16 | Ralf Dujmovits | 1990–2009 | 1961 | 47 | ||

| 17 | 9 | Veikka Gustafsson | 1993–2009 | 1968 | 41 | |

| 18 | Andrew Lock | 1993–2009 | 1961 | 48 | ||

| 19 | 10 | João Garcia | 1993–2010 | 1967 | 43 | |

| 20 | Piotr Pustelnik | 1990–2010 | 1951 | 58 | ||

| 21 | Edurne Pasaban | 2001–2010 | 1973 | 36 | ||

| 22 | Abele Blanc | 1992–2011 | 1954 | 56 | ||

| 23 | Mingma Sherpa | 2000–2011 | 1978 | 33 | ||

| 24 | 11 | Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner | 1998–2011 | 1970 | 40 | |

| 25 | Vassily Pivtsov | 2001–2011 | 1975 | 36 | ||

| 26 | 12 | Maxut Zhumayev | 2001–2011 | 1977 | 34 | |

| 27 | Kim Jae-soo | 2000–2011 | 1961 | 50 | ||

| 28 | 13 | Mario Panzeri | 1988–2012 | 1964 | 48 | |

| 29 | Hirotaka Takeuchi | 1995–2012 | 1971 | 41 | ||

| 30 | Chhang Dawa Sherpa | 2001–2013 | 1982 | 30 | ||

| 31 | 14 | Kim Chang-ho | 2005–2013 | 1970 | 43 | |

| 32 | Jorge Egocheaga | 2002–2014 | 1968 | 45 | ||

| 33 | 15 | Radek Jaroš | 1998–2014 | 1964 | 50 | |

| 34/35 | 16/17 | Nives Meroi | 1998–2017 | 1961 | 55 | |

| 34/35 | 16/17 | Romano Benet | 1998–2017 | 1962 | 55 | |

| 36 | 18 | Peter Hámor | 1998–2017 | 1964 | 52 | |

| 37 | 19 | Azim Gheychisaz | 2008–2017 | 1981 | 37 | |

| 38 | Ferran Latorre | 1999–2017 | 1970 | 46 | ||

| 39 | 20 | Òscar Cadiach | 1984–2017 | 1952 | 64 | |

| 40 | Kim Mi-gon | 2000–2018 | 1973 | 45 | ||

| 41 | Sanu Sherpa | 2006–2019 | 1975 | 44 | ||

| 42 | Nirmal Purja | 2014–2019 | 1983 | 36 | ||

| 43 | Mingma Gyabu Sherpa | 2010–2019 | 1989 | 30 | ||

| 44 | Kim Hong-bin | 2006–2021 | 1964 | 57 |

Disputed Climbs

Sometimes, there isn't enough proof to confirm a climb. These are called "disputed ascents." The person who keeps the best records for Himalayan climbs is Elizabeth Hawley. Her The Himalayan Database is usually the main source for checking these climbs.

Cho Oyu can be a tricky mountain. Its true top is a small hump about 30 minutes from the main plateau. You need clear weather to see Mount Everest from the real summit. Shishapangma is another tricky one because it has two tops that are very close in height but can take up to two hours to climb between them. For example, Elizabeth Hawley thought that Ed Viesturs didn't reach the true summit of Shishapangma. So, he climbed it again to make sure his ascent was clear.

Gallery

-

No. 1 – Everest

-

No. 2 – K2

-

No. 3 – Kangchenjunga

-

No. 4 – Lhotse

-

No. 5 – Makalu

-

No. 6 – Cho Oyu

-

No. 7 – Dhaulagiri

-

No. 8 – Manaslu

-

No. 9 – Nanga Parbat

-

No. 10 – Annapurna

-

No. 11 – Gasherbrum I

-

No. 12 – Broad Peak

-

No. 13 – Gasherbrum II

-

No. 14 – Shishapangma

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ochomil para niños

In Spanish: Ochomil para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |