1955 British Kangchenjunga expedition facts for kids

The 1955 British Kangchenjunga expedition was a famous trip where climbers successfully reached the top of Kangchenjunga for the first time. Kangchenjunga is the third highest mountain in the world, standing at about 28,168 feet (8,586 meters) tall. The climbers respected a special request from the local authorities in Sikkim: they stopped about five feet below the very top of the mountain, so they didn't actually step on the summit.

Two climbers, George Band and Joe Brown, reached this point on May 25, 1955. The next day, Norman Hardie and Tony Streather followed them. The expedition was led by Charles Evans, who had also been a leader on the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition two years earlier.

The team traveled from Darjeeling in India, through Nepal, to the Yalung Valley. They tried one climbing path that another team had explored the year before, but it didn't work out. Instead, they found success on a different route up the Yalung Face, a path first tried way back in 1905. Many people, both then and now, see this climb as an even bigger achievement than the first climb of Mount Everest.

Contents

Why Kangchenjunga Was So Important

The World's Highest Unclimbed Peak

After Mount Everest was climbed in 1953 and K2 in 1954, Kangchenjunga became the highest mountain in the world that no one had ever climbed. This giant mountain sits right on the border between Nepal and Sikkim. You can see it clearly from Darjeeling in West Bengal, India.

In 1955, Sikkim had some control over its own rules and didn't want anyone trying to climb the mountain. However, Nepal had started allowing a few climbing trips since 1950. So, Nepal agreed to let the British team try to climb Kangchenjunga from its western side.

Exploring the Mountain's Challenges

Kangchenjunga is a very active mountain, with avalanches often sliding down its sides. It's also located where the monsoon winds from the Bay of Bengal hit, meaning the rainy season lasts longer here than on other very tall mountains.

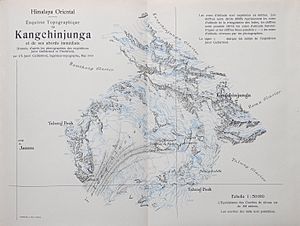

For many years, different teams had explored Kangchenjunga. The two routes the 1955 expedition tried were both on the Yalung Face. One was explored in 1905 by a Swiss team, and the other by John Kempe in 1954. Kempe's report helped the Alpine Club decide to support this new expedition.

The Expedition Team

The team was led by Charles Evans, who was 36 years old. He had been a deputy leader on the 1953 Mount Everest expedition. Here are some other key members:

- Norman Hardie (30 years old), from New Zealand, was the deputy leader.

- George Band (26 years old) had also been on the 1953 Everest trip and was in charge of food.

- Joe Brown (24 years old) was a very skilled rock climber.

- John Clegg (29 years old) was the expedition doctor.

- John Jackson (34 years old) had a lot of experience in the Himalayas.

- Tom McKinnon (42 years old) was the photographer.

- Neil Mather (28 years old) was an expert in ice and snow climbing.

- Tony Streather (29 years old) had wide climbing experience and was in charge of the porters.

- Dawa Tensing (around 45 years old) was the sirdar, or chief Sherpa. He had helped Evans on previous expeditions.

- Annullu, the deputy sirdar, also had a lot of experience.

The team also included about 30 Sherpas and 300 porters who helped carry supplies.

Climbing Gear and Oxygen

Climbing equipment had improved a lot for the 1953 Everest expedition, so not many big changes were needed for 1955. They used special high-altitude boots that allowed for extra layers and crampons. Their oxygen equipment was also better designed.

Climbers used extra oxygen above Camp 3, and Sherpas used it above Camp 5. They had some experimental oxygen sets, but mainly relied on the standard "open-circuit" systems. These systems were lighter than the Everest ones. However, they had a problem: the rubber valves would leak when they got cold overnight. This often delayed their early morning starts while they warmed up the equipment. Another issue was that climbers lost weight, so their face masks didn't fit well, causing gas to leak. This could also fog up their goggles, and taking them off risked getting snowblind. In total, about 6 tons of supplies had to be carried from Darjeeling!

The Expedition Journey

Setting Off from Darjeeling

Just before the team sailed from Liverpool on February 12, 1955, they learned that the Sikkim government didn't want them to climb the mountain at all, even from the Nepal side. So, before leaving Darjeeling, Charles Evans went to meet the prime minister of Sikkim. They reached an agreement: the expedition could go ahead, but once they were sure they could reach the summit, they had to stop about five feet below it. They also promised not to disturb the area around the summit.

The Long Trek to Base Camp

On March 14, the team left Darjeeling. They traveled by truck for 16 miles (26 km) to Mane Bhanjyang, the last big village before their 10-day trek began. They followed a track up the Singalila Ridge, where they found rest houses. They then turned west into the jungles of Nepal.

After much walking through cultivated land and jungle, they reached the Yalung Valley. Finally, they arrived at the Yalung glacier. At about 13,000 feet (4,000 meters), the porters were paid and sent back because the path up the glacier was too hard for them. The team set up a large "Yalung Camp" to get used to the high altitude. They also took measurements of the Kangchenjunga's Yalung, or southwest, face.

The trek to Yalung Camp took 10 days. After getting used to the altitude, they started a four-day trek up the glacier to establish a higher base camp. This new base camp was at the foot of "Kempe's Buttress," a route suggested by the previous year's exploration. The weather was very bad, and since the porters were gone, the climbers had to carry everything themselves. They chose the right side of the glacier to avoid avalanches.

Trying the First Route

Kempe's Buttress was a rocky section next to a huge icefall. From the top of the buttress, at about 19,500 feet (5,900 meters), the team hoped to find a way up the icefall. George Band and Norman Hardie spent two days trying to get onto the icefall. Charles Evans and John Jackson joined them, but they couldn't make any more progress.

George Band, who had climbed Mount Everest's difficult Khumbu Icefall, said this icefall made the Khumbu look like a "children's playground." It seemed they might be stopped very early! Luckily, Norman Hardie spotted a small glacier on the other side of the main glacier. This new path led to a spot they called the "Hump." So, they decided to give up on the first route and try this new one, which meant moving their base camp again.

| First Attempt: Kempe's Buttress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Height | Date (1955) | What happened | |

| feet | meters | |||

| Base | 18,000 | 5,500 | April 12 | Kempe's second base camp |

| Camp 1 | 19,500 | 5,900 | April 19 | Top of Kempe's buttress |

| Highest point |

20,000 | 6,100 | April 22 | They reached this height before finding a new route. |

Trying a New Route

The new base camp was set up at a place called "Pache's Grave." This was where four climbers from a 1905 expedition had died in an avalanche. A wooden cross and gravestone were still there.

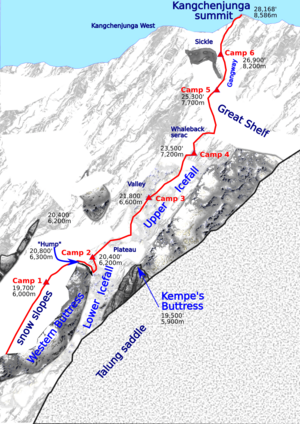

Evans' new plan was to climb to the Hump, then go down to the Lower Icefall. From there, they would climb to a flat area called the "Plateau" between the Lower and Upper Icefalls. After that, they hoped to follow the "Great Shelf," a snow ledge, to a rocky area called the "Sickle." From the Sickle, a steep snow path, or "Gangway," would lead them close to the summit.

| Camp Locations on the New Route | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Height | Date (1955) | Description | |

| feet | meters | |||

| Base | 18,100 | 5,500 | April 23 | At Pache's Grave |

| Camp 1 | 19,700 | 6,000 | April 26 | Above a narrow section |

| Camp 2 | 20,400 | 6,200 | April 28 | On the "Plateau" above the Lower Icefall |

| Camp 3 | 21,800 | 6,600 | May 4 | Advanced Base Camp below the Upper Icefall |

| Camp 4 | 23,500 | 7,200 | May 12 | Above the Upper Icefall, near the Great Shelf |

| Camp 5 | 25,300 | 7,700 | May 13 | A ledge below an ice cliff, near the "Sickle" and "Gangway" |

| Camp 6 | 26,900 | 8,200 | May 24 | A small site dug into the "Gangway" |

| Summit | 28,168 | 8,586 | May 25 | Climbers stopped five feet below the top. |

Climbing the Icefalls

By April 26, George Band and Norman Hardie had set up Camp 1 on the very steep snow slopes. To go higher, they had to cross a 20-foot (6-meter) wide crevasse, which they eventually made safe for the Sherpas using a ladder and ropes. They climbed up to the Hump and then descended about 400 feet (120 meters) to the icefall.

They struggled up the edge of the icefall to reach a large, safe plateau between the Upper and Lower Icefalls. This was a great spot for Camp 2, which Evans and Brown quickly set up. For three weeks, without missing a single day, supplies were carried between Base Camp and Camp 2, stopping overnight at Camp 1.

On April 29, Evans and Brown were near the future site of Camp 3 when a storm hit. They had to go back to Camp 2 because of deep snow and avalanches. Food became short. It wasn't until May 4 that they could reach the Camp 3 site. By May 9, it was fully set up as an Advanced Base Camp at 21,800 feet (6,600 meters). On May 12, Evans and Hardie set up Camp 4. The next day, they reached the Great Shelf and found a good spot for Camp 5 at 25,300 feet (7,700 meters), the highest point ever reached on the mountain at that time.

High Camps and Summit Plans

Tony Streather, Neil Mather, and their Sherpas started moving supplies to Camp 4, while the other climbers went back to Base Camp to rest. Evans then announced the plan for the summit attempts. John Jackson, Tom McKinnon, and their Sherpas would stock Camp 5. George Band and Joe Brown would be the first pair to try for the summit, supported by Evans, Mather, and four Sherpas. The support team would set up Camp 6 as high as possible. Norman Hardie and Tony Streather would be the second summit team, moving up a day later.

Things didn't start smoothly. Streather became snowblind and couldn't go above Camp 4. Many supplies had to be left below Camp 5. Jackson and McKinnon couldn't get down to Camp 3, so they stayed at Camp 4 with Brown and Band. A blizzard hit that night, making everyone worry the monsoon season was starting.

However, the storm eased. Evans, Mather, Brown, Band, and three Sherpas set off for Camp 5, only to find that an avalanche had swept away many of the supplies. After an unexpected rest day at Camp 5, they made good progress. But when they reached the planned height for Camp 6, 26,900 feet (8,200 meters), there was no suitable spot. They had to dig a small ledge out of a steep snow slope for two hours to fit their tent. Despite the tough conditions, they had a warm meal. Band and Brown stayed at Camp 6 that night, wearing all their clothes and using a low flow of oxygen.

Reaching the Summit

May 25, 1955 – Brown and Band

At 5:00 AM, the day looked clear. By 8:15 AM, Brown and Band were ready to climb the Gangway. The snow conditions were good. Their plan was to turn off the Gangway onto the southwest face to reach the ridge closer to the summit. They turned too early and wasted 1½ hours backtracking.

The next part involved rock climbing and then a very steep snow slope. They used a low amount of oxygen, which seemed to help Brown more than Band, so Brown led the rest of the way. After more than five hours of climbing, they reached the ridge. The summit was only about 400 feet (120 meters) above them.

They rested briefly and had a snack. By 2:00 PM, they had only two hours of oxygen left. They knew they had to reach the summit by 3:00 PM to avoid having to camp out in an emergency on the way down. Brown led a final rock climb up a 20-foot (6-meter) crack. This climb was very difficult, especially at that altitude, and required more oxygen. From the top of the crack, they were surprised to see the actual summit was just 20 feet (6 meters) away and five feet (1.5 meters) higher. It was 2:45 PM on May 25, 1955. As agreed, they did not step onto the very top of the mountain. Clouds blocked most of the view, but they could see the highest peaks like Makalu, Lhotse, and Everest, about 80 miles (130 km) away.

They started their descent, leaving their empty oxygen sets after an hour. As it got dark, they reached their tent. Hardie and Streather were there, ready for a second attempt if the first had failed. Band and Brown thought it was too dangerous to continue down to Camp 5 in the dark. So, four men had to spend the night in the small two-person tent, which hung over the edge of the narrow ledge. Brown was in a lot of pain from snowblindness during the night.

May 26, 1955 – Hardie and Streather

The next morning, Hardie and Streather decided to try for the summit. They followed the same route but avoided the detour the first pair had made. At the rock wall just before the summit, Brown and Band had left a rope to help them climb. Hardie and Streather went further around the base of the wall and found an easier snow slope that led them just below the summit. They reached this point at 12:15 PM. They spent an hour at the top before successfully descending. Hardie and Streather had carried more oxygen than Band and Brown, but unfortunately, about half of it leaked away. Streather ended up having to descend without extra oxygen. They stayed at Camp 6 overnight and then continued down to Camp 5 the next day, where Evans and Dawa Tensing were waiting to support them.

Leaving the Mountain

Sadly, Pemi Dorje, one of the Sherpas, died at base camp on May 26. He had fallen into a crevasse on May 19 and became very tired helping carry supplies to Camp 5. Although he made it safely back to base camp and seemed to be getting better, he passed away.

As the teams started coming down the mountain, the snow and ice were melting quickly, making some snow bridges and ladders very dangerous. Evans decided they needed to leave the mountain fast, taking only what they could easily carry and leaving the rest behind. By May 28, the expedition had left the mountain.

On their way in, they had avoided high passes by going through the jungle of Nepal. On the way back, in heavy rain, they went up onto the ridge further north to avoid leeches that were common in the valleys during monsoon season. By June 13, they were back in Darjeeling.

What Made This Climb Special

The news of the Kangchenjunga climb made headlines around the world, but it didn't have the same huge impact as the first climbs of Everest or K2. None of the team members received special national awards at the time. The reports written by Evans and Band didn't focus on national pride; they didn't even mention flags being placed on the summit.

In 1956, Francis Farquhar, a climbing expert, wrote that the Kangchenjunga climb deserved much more praise. He said it was a greater climbing achievement than Everest in many ways. While not quite the highest, it was still in the same top class. He noted that Kangchenjunga was unmatched in its huge glaciers, cliffs, and endless ridges, and until Evans' team, it seemed like it might be impossible to climb.

More than fifty years later, Doug Scott, who had climbed both Everest and Kangchenjunga, called it "a remarkable climb and one of the finest achievements in British mountaineering." He explained that on Everest, only 900 feet of the route was unexplored before the first climb. But on Kangchenjunga, there were 9,000 feet of unknown territory, and it turned out to be more technically difficult than Everest, especially near the top.

In 2005, Ed Douglas wrote for the British Mountaineering Council that the nation might have "forgotten a unique sporting achievement."

Charles Evans himself, back in 1956, had a wise thought about the Sherpas he admired so much: "It would be simple to think they can never change. Except for those with the strongest character, it's unlikely they can resist the big growth of Himalayan travel, and the arrival of groups who think only money matters. We are lucky to have been their friends in days when they haven't been exposed to harm."

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |