Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah facts for kids

Quick facts for kids al-Mahdi Billahالمهدي بالله |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gold dinar of al-Mahdi bi'llah, minted at Kairouan, 912 CE

|

|||||

| Imam–Caliph of the Fatimid Dynasty | |||||

| Reign | 27 August 909 – 3 April 934 | ||||

| Successor | al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah | ||||

| Born | Sa'id or Ali ibn al-Husayn 31 July 874 Askar Mukram, Khuzistan |

||||

| Died | 3 April 934 (aged 59-60) Mahdiya |

||||

| Issue | al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah | ||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Fatimid | ||||

| Father | al-Husayn ibn Ahmad (Abdallah al-Radi) | ||||

| Religion | Isma'ili Shi'a Islam | ||||

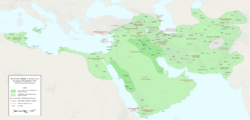

Al-Mahdi Billah was a very important leader in Islamic history. He founded the Fatimid Caliphate, a powerful empire that was the only major Shi'a caliphate ever. He was also the eleventh Imam for the Isma'ili branch of Shi'ism. He was born on July 31, 874, and died on April 3, 934.

Al-Mahdi was born as Sa'id ibn al-Husayn in a place called Askar Mukram. His family secretly led a group called the Isma'ili da'wa, which means 'invitation'. This group believed in a hidden leader, the mahdi, who would one day appear to bring justice. Sa'id became the leader of this group.

However, when Sa'id said that he and his family were the true hidden imams, some followers disagreed. This caused a split in the movement in 899. Those who disagreed became known as the Qarmatians. After this, some of his supporters started a rebellion in Syria without his permission. This made the Abbasid rulers suspicious, forcing Sa'id to flee. He traveled from Syria to Egypt and finally to Sijilmasa in what is now Morocco. He lived there as a merchant.

In 909, one of his missionaries, Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i, led a group of Kutama Berbers to overthrow the rulers of Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia). Al-Mahdi then became the new ruler, or caliph, in January 910. He wanted to expand his empire, but he faced many challenges. He had to deal with revolts from people who were unhappy with his rule or the behavior of his Kutama soldiers. He also tried to conquer Egypt twice, but the Abbasids stopped him. He fought with the Byzantine Empire in southern Italy and tried to control the Berber tribes in the west. In 921, he moved his capital to a new, strong city he built called Mahdiya. After he died in 934, his son, al-Qa'im, took over.

Early Life and Leadership

Family and Childhood

Al-Mahdi Billah was born Sa'id ibn al-Husayn in Khuzistan on July 31, 874. His father died when he was young, so he moved to Salamiya in Syria to live with his uncle, Abu Ali Muhammad. A boy named Ja'far, who was like a brother to Sa'id, joined him and later became his trusted helper.

Sa'id's family had a secret mission. They led a hidden religious and political group called the Isma'ili da'wa. This group worked to prepare people for the return of a hidden leader, the mahdi, who would bring peace and justice. The Isma'ilis believed this mahdi was Muhammad ibn Isma'il, a descendant of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Sa'id's uncle, Abu'l-Shalaghlagh, had no other heirs, so Sa'id was chosen to lead the da'wa after him. Sa'id's only son, Abd al-Rahman, who would later become Caliph al-Qa'im, was born in 893.

Leading the Isma'ili Movement

The Isma'ili movement grew very quickly in the late 800s. Many people were unhappy with the Abbasid rulers and were looking for a new leader. Isma'ili missionaries, called da'is, spread their message across the Muslim world, from Yemen to North Africa.

When Sa'id took over the leadership, he made a big change. He announced that he, not Muhammad ibn Isma'il, was the true hidden imam. This caused a major split. Some leaders, like Hamdan Qarmat, refused to accept Sa'id's claim. These groups became known as the "Qarmatians." They mostly lived in the eastern parts of the Islamic world.

Escaping Danger

After the split, some of Sa'id's eager followers, like Zakarawayh's sons, started a rebellion in Syria in 902. They hoped to force Sa'id to reveal himself as the mahdi. However, this rebellion drew the attention of the Abbasid government.

Sa'id learned that the Abbasids knew who he was. He quickly left Salamiya at night with his son and a few trusted companions. They traveled south, reaching Ramla, where a secret Isma'ili supporter helped them. They barely escaped capture.

The Bedouin rebels, expecting Sa'id to join them, were disappointed when he stayed hidden. The Abbasid army eventually crushed their rebellion in November 903. The rebels, feeling betrayed, destroyed Sa'id's home in Salamiya and killed his family members there. Sa'id's women were later rescued by a loyal slave.

Journey to Sijilmasa

Sa'id had to flee again, this time to Egypt, which was then ruled by the Tulunid dynasty. He arrived in Fustat (near modern Cairo) in 904, pretending to be a rich merchant. But the Abbasids were still looking for him.

In 905, Abbasid troops took over Egypt, forcing Sa'id to move again. Instead of going to Yemen, where other Isma'ili leaders were powerful, he decided to go west to the Maghreb (North Africa). This surprised his followers, as the Maghreb was considered wild and far from the main Islamic centers. However, a missionary named Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i had gained many followers among the Kutama Berbers there.

Sa'id traveled with a merchant caravan. After some difficulties, he arrived in Sijilmasa, a desert oasis town in modern Morocco. He lived there as a merchant for four years, staying in touch with Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i. The local ruler knew Sa'id's true identity but did not act against him.

Becoming Caliph

Taking Power in Ifriqiya

In March 909, Abu Abdallah and his Kutama army defeated the Aghlabid rulers of Ifriqiya. The Aghlabid emir fled, and Abu Abdallah took control of the capital, Raqqada.

Abu Abdallah then went to Sijilmasa to bring Sa'id to power. The ruler of Sijilmasa had Sa'id arrested, but the Kutama army quickly arrived and freed him. On August 27, 909, Sa'id was officially declared the new ruler.

The army then marched back to Ifriqiya. On January 4, 910, Sa'id entered Raqqada. The next day, he was formally announced as "Abdallah Abu Muhammad, the Imam rightly guided by God, the Commander of the Faithful." This marked the beginning of the Fatimid Caliphate.

Challenges of a New Empire

Becoming caliph was a huge step for the Isma'ili movement. For the first time in centuries, a descendant of Ali was ruling a large part of the Muslim world. Al-Mahdi claimed he had a divine right to rule the entire world.

However, his followers had expected a miracle-working mahdi. Al-Mahdi, a former merchant, did not fit this image. He was a practical ruler, focusing on building a state. He used his new title, "the Imam rightly guided by God," to show he was an imam, but not necessarily the final messiah. He also made his son, Abu'l-Qasim Muhammad, his heir, shifting some of the messianic expectations to him.

The new Fatimid state relied heavily on the Kutama Berbers, who had brought al-Mahdi to power. While they were essential, their behavior often caused problems with other tribes and city dwellers. Al-Mahdi had to use many officials from the old Aghlabid government, even if their loyalty was uncertain. He also created new government departments, similar to the Abbasids.

Abu Abdallah's Downfall

Many Kutama leaders, including Abu Abdallah, became disappointed with al-Mahdi. They felt he was too focused on luxury and not on the spiritual mission. Some even accused him of being a fraud.

In February 911, al-Mahdi learned that Abu Abdallah and others were plotting against him. He acted first. Abu Abdallah and his brother were killed by loyal Kutama soldiers in the caliph's palace. Al-Mahdi then executed other plotters.

Rebellions and Control

After Abu Abdallah's death, there were many revolts against the Kutama and al-Mahdi's rule. In 911, a fight in the old capital led to an uprising. In 912, all Kutama soldiers in Kairouan were killed in a riot.

Another rebellion started among the Kutama themselves. A young boy was declared the "true mahdi." In response, al-Mahdi officially named his son, Abu'l-Qasim Muhammad, as his heir. He gave him the title al-qa'im bi-amr Allah ('He who executes God's command'). His son then led the army to crush the rebellion in June 912.

Later Years and Expansion

Building Mahdiya

The revolts showed that Raqqada, his capital, was not safe enough. In 912, al-Mahdi started looking for a new, stronger location. He chose a small, rocky peninsula called Jumma, which was easy to defend from land.

Construction began in 916. The new city, Mahdiya, had strong walls, a large mosque, two palaces, and other buildings for the government. It was designed to be a palace city, a military base, and a treasury all in one. Only the Fatimid family and their most loyal supporters lived there. The city was officially moved to Mahdiya in February 921.

Expanding the Empire

Al-Mahdi felt he had to expand his empire to prove his power. He aimed to conquer lands from his Muslim rivals, the Abbasids in the east and the Umayyads in the west, and from the Christian Byzantine Empire in the north.

East: Egypt and Cyrenaica

Al-Mahdi wanted to conquer Egypt because it was the gateway to Syria and Iraq, the heartlands of the Islamic world.

First, he took Tripoli. The local people there rebelled against the Kutama soldiers and high taxes. Al-Mahdi's son, al-Qa'im, led an army and navy to retake Tripoli in June 913.

Al-Mahdi also hoped for help from his followers in Yemen, but their leader, Ibn al-Fadl, declared himself the mahdi in 911 and turned against al-Mahdi. This weakened the Fatimid position in Yemen.

First Invasion of Egypt

The first Fatimid invasion of Egypt began in January 914. The army, led by Habasa ibn Yusuf, quickly captured Barqa (in Cyrenaica). Al-Qa'im was sent to take command, but Habasa pushed ahead and entered Alexandria in August.

The Abbasid government in Baghdad was shocked. They sent a large army to defend Egypt. The Fatimid army struggled with discipline and disagreements among its leaders. Al-Qa'im and Habasa argued. Habasa eventually left the campaign. Al-Qa'im had to retreat from Alexandria in May 915, losing much equipment. Cyrenaica then rebelled against Fatimid rule.

This failure caused more unrest. Habasa and his brother Ghazwiyya led another revolt, but it was quickly crushed, and they were executed.

Second Invasion of Egypt

Al-Mahdi immediately planned a second invasion. First, he recaptured Cyrenaica in April 917. The main invasion of Egypt began in April 919, led by al-Qa'im. Alexandria was taken without a fight.

However, the Abbasids again defended the Nile crossing. In March 920, the Fatimid navy was destroyed by the Abbasid fleet. Al-Qa'im's army was cut off from supplies. He tried to negotiate with the Abbasids, but he refused to give up his claim to rule the entire Islamic world.

In spring 921, the Abbasids attacked, forcing al-Qa'im to abandon his equipment and retreat across the desert back to Barqa.

West: Maghreb and Spain

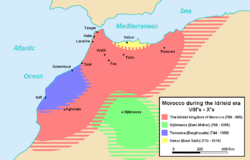

The Fatimids also faced challenges in the western Maghreb (modern Morocco and Algeria). Many Berber tribes resisted their rule and heavy taxes.

Al-Mahdi's forces tried to control the mountainous areas, but it was difficult. In 922, a Kutama commander and his men were killed trying to impose Fatimid rule in the Aurès Mountains.

The Zenata Berbers, led by Ibn Khazar, constantly fought against Fatimid control of Tahert, an important outpost. In 924, the Fatimid governor was killed. Al-Mahdi had to send al-Qa'im to deal with the revolt in person in 927. Al-Qa'im established a new city, al-Muhammadiya, to strengthen Fatimid control. He eventually defeated Ibn Khazar in March 928.

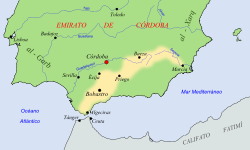

Rivalry with Umayyads

Al-Mahdi also had a powerful rival in the west: the Umayyad rulers of al-Andalus (Islamic Spain). This rivalry was mostly through propaganda and supporting different groups. The Umayyads were worried about the Fatimid threat. In 927, they captured Melilla on the Moroccan coast, and in 931, Ceuta, to establish military bases. The Umayyads also allied with Ibn Khazar, the Zenata leader, against the Fatimids. In 929, the Umayyad ruler, Abd al-Rahman III, even declared himself caliph, directly challenging al-Mahdi's claim to be the leader of all Muslims.

Attempts to Conquer Morocco

In 917, a Fatimid army attacked Nakur on the Moroccan coast. They also forced the Idrisid ruler of Fes to accept Fatimid rule. However, when the Fatimid army left, the exiled princes of Nakur returned with Umayyad support and retook their city.

In 921, the Fatimids returned, deposing the Idrisid ruler of Fes and installing their own governor. They also retook Sijilmasa. However, Fatimid control over these distant areas was weak. In 932, the Fatimid governor in the west, Ibn Abi'l-Afiya, switched his loyalty to the Umayyads. This caused Fatimid rule in the far west to collapse.

North: Sicily and Italy

Al-Mahdi also inherited Sicily from the Aghlabids. This island was a key battleground with the Byzantine Empire. The Fatimids used this war to show themselves as champions of Islam against the Christians.

Revolts in Sicily

In 910, al-Mahdi sent his first governor to Sicily. But the Sicilians rebelled against his heavy taxes and imprisoned him. The island then revolted in 913 under an Aghlabid leader, who recognized the Abbasid caliph instead of al-Mahdi.

In July 914, the Sicilian fleet attacked the coasts of Ifriqiya, burning Fatimid ships and taking prisoners. However, the Fatimids eventually regained control. Palermo, the island's capital, resisted until March 917. After its surrender, a Kutama garrison was installed, bringing relative peace to the island for about twenty years.

War with the Byzantines

In 918, the Fatimids attacked Reggio Calabria in Italy. In 922, they attacked a fortress near Reggio. In 924, a large Fatimid fleet raided Bruzzano and then sacked Oria in Apulia, taking over 11,000 prisoners. The Fatimid commander returned to Mahdiya in triumph in September 925.

Around this time, al-Mahdi even talked with the Bulgarian emperor, Simeon I. Simeon wanted to attack the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, by land, and suggested the Fatimids attack by sea. They would share the spoils. However, the ship carrying their envoys was captured by the Byzantines, and the plan failed.

Warfare with the Byzantines continued. In 928, a Fatimid fleet attacked Apulia and sacked Taranto and Otranto. They also forced Salerno and Naples to pay money to avoid being attacked. In 929, they defeated a Byzantine general and sacked Termoli. Al-Mahdi planned a larger attack, but a truce was signed in 931.

Al-Mahdi's Legacy

Al-Mahdi was a strong and wise leader. He successfully created a new state and ended the secrecy of the Isma'ili movement. He managed his provinces well and fought many wars to expand his empire.

He focused on building a strong state and dealing with real-world problems. It was left to later Fatimid leaders, like the fourth caliph, al-Mu'izz, to further develop the Isma'ili religious beliefs for the new empire. Al-Mu'izz also tried to bring the Qarmatians back into the Fatimid fold, with some success.

|

See also

Template:KIDDLE XL START  In Spanish: Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah para niños Template:KIDDLE XL END

In Spanish: Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah para niños Template:KIDDLE XL END

- List of Ismaili imams

- List of Mahdi claimants

Sources

- Benchekroun, Chafik T. (2016). "Les Idrissides entre Fatimides et Omeyyades" (in French). Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée 139: 29–50. doi:10.4000/remmm.9412.

- Benchekroun, Chafik T. (2018). "Idrīsids". Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2007). Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13542-8. https://archive.org/details/artsofcityvictor0000bloo.

- Brett, Michael (1996). "The Realm of the Imām: The Faṭīmids in the Tenth Century". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 59 (3): 431–449.

- Brett, Michael (2001). The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century CE. The Medieval Mediterranean. 30. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9004117415. https://books.google.com/books?id=BqCdfhW3nVwC.

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.

- Canard, Marius (1942–1947). "L'impérialisme des Fatimides et leur propagande" (in fr). Annales de l'Institut d'études orientales VI: 156–193.

- Canard, Marius (1965). "Fāṭimids". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 850–862.

- Dachraoui, Farhat (1981) (in French). Le Califat Fatimide au Maghreb (296-365 H. / 909-975 Jc.). Historie Politique et Institutions (PhD thesis). Tunis.

- Dachraoui, F. (1986). "al-Mahdī ʿUbayd Allāh". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1242–1244.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). [Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines] (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2. Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books.

- Eustache, D. (1971). "Idrīsids". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1035–1037.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991). [Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century]. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7. Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books.

- Hadda, Lamia (2008) (in it). Nella Tunisia medievale. Architettura e decorazione islamica (IX-XVI secolo). Naples: Liguori editore. ISBN 978-88-207-4192-1.

- Halm, Heinz (1991) (in de). Das Reich des Mahdi: Der Aufstieg der Fatimiden. Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-35497-7.

- Halm, Heinz (2014). "Fāṭimids". Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). [Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century] (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7. Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books.

- Lev, Yaacov (1984). "The Fāṭimid Navy, Byzantium and the Mediterranean Sea, 909–1036 CE/297–427 AH". Byzantion 54: 220–252. ISSN 0378-2506.

- Lev, Yaacov (1988). "The Fāṭimids and Egypt 301–358/914–969". Arabica 35 (2): 186–196. doi:10.1163/157005888X00332.

- Lev, Yaacov (1995). "The Fāṭimids and Byzantium, 10th–12th Centuries". Graeco-Arabica 6: 190–208. OCLC 183390203.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1978). "Ḳarmaṭī". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 660–665.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1991). "Manṣūr al-Yaman". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 438–439.

- Manzano, Eduardo (2019) (in Spanish). La corte del califa: Cuatro años en la Córdoba de los omeyas. Barcelona: Editorial Crítica. ISBN 978-8-49199028-4.

- Metcalfe, Alex (2009). The Muslims of Medieval Italy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2008-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=VRXTzPOly-oC.

- Öz, Mustafa (2012). "Ubeydullāh el-Mehdî". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 42 (Tütün – Vehran). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. 23–25.

- Walker, Paul E. (1998). [Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books "The Ismāʿīlī Daʿwa and the Fāṭimid Caliphate"]. The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–150. ISBN 0-521-47137-0. Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah at Google Books.

|

Abd Allah al-Mahdi Billah

Fatimid dynasty

Born: 31 July 874 Died: 3 April 934 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title | Fatimid Caliph 909–934 |

Succeeded by al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah |

| Shī‘a Islam titles | ||

| Preceded by Abd Allah al-Radi (in concealment) |

11th Isma'ili Imam 881/2–934 |

Succeeded by al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah |

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |