Alejandro Toledo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alejandro Toledo

|

|

|---|---|

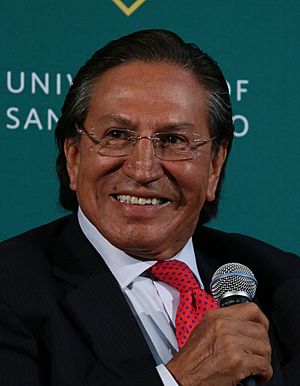

Toledo in 2015

|

|

| 56th President of Peru | |

| In office 28 July 2001 – 28 July 2006 |

|

| Prime Minister | Roberto Dañino Luis Solari Beatriz Merino Carlos Ferrero Pedro Pablo Kuczynski |

| Vice President | 1st Vice President Raúl Diez Canseco (2001–2004) 2nd Vice President David Waisman |

| Preceded by | Valentín Paniagua |

| Succeeded by | Alan García |

| President of Possible Peru | |

| In office 1 March 1994 – 13 July 2017 |

|

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Party dissolved |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Alejandro Celestino Toledo Manrique

28 March 1946 Cabana, Peru |

| Political party | Possible Peru (1994–2017) |

| Spouse | Eliane Karp |

| Alma mater | University of San Francisco (BA) Stanford University (MA, PhD) |

| Profession | Economist, politician, academic |

Alejandro Celestino Toledo Manrique (born March 28, 1946) is a Peruvian politician who served as the President of Peru from 2001 to 2006. He became a major political figure after leading the opposition against former president Alberto Fujimori.

Before becoming president, Toledo worked as an economist and professor. He studied at the University of San Francisco and Stanford University in the United States. He founded his own political party, Possible Peru, and ran for president several times. In 2001, he won the election and became Peru's leader.

After his presidency, Toledo faced serious legal challenges related to his time in office. In 2024, a court in Peru found that he had broken important laws. As a result, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Alejandro Toledo was born into a poor family of Quechuan heritage in a small town in the Ancash Department of Peru. He was one of sixteen brothers and sisters. His family moved to the city of Chimbote when he was six years old.

As a child, Toledo worked to help his family by shining shoes and selling newspapers. Even though his father wanted him to leave school to get a full-time job, his teachers encouraged him to continue his studies. He worked nights and weekends to stay in school.

Toledo's life changed when two American Peace Corps volunteers stayed with his family. They were impressed by his hard work and helped him apply for a scholarship to study in the United States. He won the scholarship and attended the University of San Francisco, where he studied economics. He later earned advanced degrees from Stanford University.

Entering Politics

Toledo first ran for president in 1995 but did not win. However, his political party, Perú Posible (Possible Peru), grew in popularity. He ran for president again in 2000 against the current president, Alberto Fujimori.

The 2000 election was very controversial. When the first results showed Toledo might win, his supporters celebrated. But later results showed Fujimori in the lead. Many people, including Toledo, believed the election was unfair. Toledo and other leaders led large protests.

Because of the protests and other problems, Fujimori left the presidency later that year. A temporary president was put in place, and new elections were held in 2001. This time, Toledo won, defeating former president Alan García. He became the first democratically elected South American president of indigenous descent in modern history.

President of Peru (2001–2006)

As president, Toledo promised to fight poverty, create jobs, and make the government more honest. His government faced many challenges, but also had several successes.

Social Programs

Toledo's government started programs to help the people of Peru.

- Healthcare: He created a free health insurance program called Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS). This program helped millions of poor people in rural areas and cities get access to doctors and medicine.

- Education: His government started Project Huascaran, which aimed to connect schools across the country to a computer network for learning. He also increased the salaries for teachers.

- Indigenous Peoples: Toledo, being of indigenous heritage himself, created a government agency to support the rights of indigenous and Afro-Peruvian people. His wife, Eliane Karp, led this agency.

A Growing Economy

During Toledo's presidency, Peru's economy grew steadily. His government encouraged foreign investment and signed free trade agreements with other countries. These agreements made it easier for Peru to sell its products around the world. This economic growth helped reduce poverty and create jobs, though many people still faced economic hardship.

Working with Other Countries

Toledo was very active in foreign relations. He worked to build strong relationships with other countries, especially in Latin America and Asia. A major achievement was the United States – Peru Trade Promotion Agreement. This agreement aimed to increase trade and investment between Peru and the United States.

He also worked to improve relationships with neighboring countries like Ecuador and Brazil, focusing on peace and economic cooperation.

Life After Presidency

After his term ended in 2006, Toledo was not allowed to run for re-election right away due to Peru's constitution. He moved to the United States and worked as a professor and researcher at Stanford University. He also founded the Global Center for Development and Democracy, an organization that works to support democracy and reduce poverty.

Toledo ran for president again in the 2011 election but finished in fourth place. He also ran in the 2016 election but did not receive much support.

Legal Troubles

In the years after his presidency, Toledo was accused of wrongdoing during his time in office. The accusations were related to how government projects, like the construction of a major highway, were handled. Authorities in Peru began an investigation.

Toledo was living in California at the time. In 2019, he was arrested by U.S. authorities after Peru requested that he be returned to face the charges. In April 2023, he was sent back to Peru. On October 21, 2024, a court found him guilty of breaking the law and sentenced him to 20 years in prison.

Awards and Honors

- He has received honorary doctorates from over 50 universities around the world.

- In 2006, the Institute of the Americas honored him with its Award for Democracy and Peace.

- He received the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles from Monaco in 2003.

Electoral history

| Year | Office | Type | Party | Main opponent | Party | Votes for Toledo | Result | Swing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | P. | ±% | |||||||||||

| 1995 | President of Peru | General | CODE - Possible Country | Alberto Fujimori | Change 90 - New Majority | 241,598 | 3.24% | 4th | N/A | Lost | N/A | |||

| 2000 | President of Peru | General | Possible Peru | Alberto Fujimori | Peru 2000 | 4,406,812 | 40.24% | 2nd | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| 2000 | President of Peru | General (second round) | Possible Peru | Alberto Fujimori | Peru 2000 | 2,086,208 | 25.66% | 2nd | +14.58% | Lost | N/A | |||

| 2001 | President of Peru | General | Possible Peru | Alan García | Peruvian Aprista Party | 3,871,167 | 36.51% | 1st | +10.85% | N/A | N/A | |||

| 2001 | President of Peru | General (second round) | Possible Peru | Alan García | Peruvian Aprista Party | 5,548,556 | 53.07% | 1st | +16.56% | Won | Gain | |||

| 2011 | President of Peru | General | Possible Peru Electoral Alliance | Ollanta Humala | Peruvian Nationalist Party | 2,289,561 | 15.64% | 4th | N/A | Lost | N/A | |||

| 2016 | President of Peru | General | Possible Peru | Keiko Fujimori | Popular Force | 200,012 | 1.30% | 8th | N/A | Lost | N/A | |||

See also

In Spanish: Alejandro Toledo para niños

In Spanish: Alejandro Toledo para niños

- Politics of Peru

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |