Alberto Fujimori facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Excelentísimo Señor

Alberto Fujimori

|

|

|---|---|

| 藤森 謙也 | |

Fujimori in 1991

|

|

| 54th President of Peru | |

| In office 28 July 1990 – 22 November 2000 |

|

| Prime Minister |

See list

Juan Carlos Hurtado Miller

Carlos Torres y Torres Lara Alfonso de los Heros Óscar de la Puente Raygada Alfonso Bustamante Efraín Goldenberg Dante Córdova Blanco Alberto Pandolfi Javier Valle Riestra Víctor Joy Way Alberto Bustamante Belaúnde Federico Salas |

| Vice President |

See list

First Vice Presidents

Máximo San Román (1990–1992) Vacant (1992–1995) Ricardo Márquez Flores (1995–2000) Francisco Tudela (July–November 2000) Second Vice Presidents Carlos García y García (1990–1992) Vacant (1992–1995) César Paredes Canto (1995–2000) Ricardo Márquez Flores (July–November 2000) |

| Preceded by | Alan García |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Paniagua |

| President of the Emergency and National Reconstruction Government | |

| In office 5 April 1992 – 9 January 1993 |

|

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Alberto Kenya Fujimori Inomoto

26 July 1938 Lima, Peru |

| Died | 11 September 2024 (aged 86) Lima, Peru |

| Political party | Popular Force (2024) Change 90 (1990–1998) Vamos Vecino (1998–2005) Sí Cumple (2005–2010) People's New Party (2007–2013) |

| Other political affiliations |

New Majority (1992–1998, non-affiliated member) Peru 2000 (1999–2001) Alliance for the Future (2005–2010) Change 21 (2018–2019) |

| Spouses |

Susana Higuchi

(m. 1974; div. 1995)Satomi Kataoka

(m. 2006) |

| Children | 4, including Keiko and Kenji |

| Relatives | Santiago Fujimori (brother) |

| Education | National Agrarian University (BS) University of Strasbourg University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (MS) |

| Signature |  |

Alberto Kenya Fujimori Inomoto (26 July 1938 – 11 September 2024) was a Peruvian politician, professor, and engineer. He served as the 54th president of Peru from 1990 to 2000. After his presidency, he faced legal challenges. On 5 December 2023, he was ordered to be released from prison. In July 2024, Fujimori announced he would run for president again in the 2026 Peruvian general election.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Alberto Fujimori was born on 28 July 1938, in Miraflores, a part of Lima, Peru. His parents, Naoichi and Mutsue Fujimori, were from Kumamoto, Japan. They moved to Peru in 1934. Some reports later suggested he might have been born in Japan.

Fujimori attended Colegio Nuestra Señora de la Merced and La Rectora School. His parents were Buddhist, but he was raised Roman Catholic. He learned to speak Spanish well, even though he spoke Japanese at home. In 1956, he finished high school in Lima.

He went to the La Molina National Agrarian University in 1957. He graduated in 1961 as an agricultural engineer, being the top student in his class. He later taught mathematics at the university. In 1964, he studied physics in France. He also earned a master's degree in mathematics from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee in the United States in 1969.

In 1974, he married Susana Higuchi. They had four children, including Keiko and Kenji, who also became politicians.

Because of his strong academic background, Fujimori became the dean of the sciences faculty at the National Agrarian University. In 1984, he was made the university's rector, a position he held until 1989. He also led the National Commission of Peruvian University Rectors twice. From 1988 to 1989, he hosted a TV show called "Concertando" on Peru's state TV channel.

Becoming President

In 1990, Fujimori ran for president as an unexpected candidate. He ran under the party called Cambio 90 ("Change 90"). He won the election, surprising many by defeating the famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa. People were unhappy with the previous president, Alan García, and his party. Fujimori promised to bring change to Peru.

During his campaign, people often called him El Chino, which means "the Chinaman." This is a common nickname for people of East Asian descent in Peru. Even though he was of Japanese heritage, Fujimori said he liked the nickname. He became one of the first leaders of East Asian descent in a Latin American country.

Presidency (1990–2000)

First Term and Economic Changes

When Fujimori became president, Peru was facing big economic problems, including very high inflation. There was also a lot of conflict within the country. Fujimori wanted to bring peace and fix the economy. He started major economic changes called "Fujishock." These changes were very different from what he had promised during his campaign.

The "Fujishock" involved removing government controls on prices and reducing government jobs. It also removed limits on foreign investment and imports. Prices for things like electricity and gasoline went up a lot. However, these changes helped Peru rejoin the global economy.

Many of these economic ideas came from a plan called the Washington Consensus, created by the IMF. Peru followed these guidelines, and the IMF helped Peru with loans. Inflation quickly dropped, and foreign money started flowing into the country. The government also sold off many state-owned businesses. Peru's old currency, the inti, was replaced with the Nuevo Sol. These changes brought economic stability and strong growth in the mid-1990s. In 1994, Peru's economy grew faster than any other country in the world.

Political Challenges

During his first term, Fujimori faced difficulties with the Peruvian Congress. The main opposition parties controlled Congress, which made it hard for him to pass his economic reforms. He also struggled to fight against the Maoist rebel group, the Shining Path. Many people were unhappy with Congress, but Fujimori's approval was higher.

On 5 April 1992, Fujimori, with the military's support, took strong action. He closed Congress, suspended the constitution, and changed the court system. This event is known as the autogolpe or "self-coup." Many Peruvians supported this action, believing it was necessary to fix the country's problems. Fujimori said it was needed to create a real and effective democracy.

However, many countries around the world strongly criticized this move. The Organization of American States (OAS) demanded that Peru return to a democratic system. Some countries stopped giving aid to Peru. Fujimori eventually agreed to hold elections for a new congress that would write a new constitution. These elections took place in November 1992.

Authoritarian Period

After the self-coup, Fujimori worked to make his position stronger. He held elections for a new congress, which would also write a new constitution. His supporters won most of the seats in this new body. In 1993, a new constitution was approved by a small margin in a public vote.

In 1994, Fujimori and his wife, Susana Higuchi, separated. She publicly accused his government of being corrupt. Their eldest daughter became the new First Lady.

Second Term

The new 1993 Constitution allowed Fujimori to run for a second term. In April 1995, he easily won reelection with a large majority of votes. His party also won many seats in Congress. One of the first things the new Congress did was to grant amnesty (legal protection) to military and police members accused of certain actions between 1980 and 1995.

During his second term, Fujimori signed a peace agreement with Ecuador to end a long-standing border dispute. This helped both countries get international money to develop their border regions. He also resolved some issues with Chile.

However, people started to worry more about freedom of speech and the press. Some opponents began calling him "Chinochet," linking his nickname to the Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet. Fujimori reportedly liked this nickname.

Third Term and Resignation

The 1993 constitution limited a president to two terms. But Fujimori's supporters in Congress passed a law that allowed him to run for a third term in 2000. Many people disagreed with this.

In the 2000 election, Fujimori did not get enough votes to win outright in the first round. His main opponent was Alejandro Toledo. There were many reports of problems with the election. International observers left the country because of these issues. In the second round, Fujimori won, but many people spoiled their ballots to protest.

After the election, there were daily protests. A big corruption scandal involving Vladimiro Montesinos, a close advisor to Fujimori, came to light. A video was broadcast showing Montesinos bribing a politician. Fujimori's support quickly fell apart.

A few days later, Fujimori announced he would call new elections and would not run himself. On 13 November, he left Peru for a meeting in Brunei. From Japan, he sent his resignation by fax. However, Congress refused to accept it. Instead, they voted to remove him from office, saying he was "permanently morally disabled."

Because both his vice presidents had resigned, Valentín Paniagua, the head of Congress, became the interim president. He oversaw new elections in 2001.

Efforts Against Rebel Groups

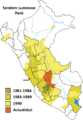

When Fujimori became president, much of Peru was affected by two main rebel groups: the Shining Path and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA). These groups controlled some areas and caused a lot of violence.

Fujimori is widely credited by many Peruvians for helping to end the Shining Path's activities. He gave the military broad powers to arrest suspected rebels and try them in secret courts. He also organized rural Peruvians into groups called "peasant patrols" to help fight the rebels.

By the end of 1992, rebel activity had decreased. Fujimori's government captured the leaders of both the MRTA and the Shining Path, including the main Shining Path leader, Abimael Guzmán. This was a big success for Fujimori.

In December 1996, MRTA militants took over the Japanese ambassador's home in Lima, holding many people hostage. After a four-month standoff, on 22 April 1997, military commandos raided the building. One hostage, two soldiers, and all 14 rebels were killed. Fujimori was seen at the scene, which boosted his image as a strong leader against terrorism.

After the Presidency (2000–2024)

Legal Challenges

After resigning, Alberto Fujimori stayed in Japan. The Peruvian Congress banned him from holding public office for ten years. Peru tried to have him sent back from Japan to face charges, but Japan refused because he had been granted Japanese citizenship.

Peruvian authorities accused Fujimori of being involved in some serious events that occurred during his presidency. They also investigated him for mismanaging money from Japanese charities.

In 2004, a report claimed that Fujimori's government had gained a lot of money through corruption. Fujimori said these legal actions were politically motivated. He tried to run for president again in 2006, but the Constitutional Court said he could not because of the ban from Congress.

In November 2005, Fujimori traveled to Chile and was arrested there. Peru then asked Chile to send him back. In September 2007, he was sent from Chile to Peru.

On 7 April 2009, a court found Fujimori responsible for certain actions during his presidency. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. On 5 December 2023, he was ordered to be released.

Illness and Death

For many years, Fujimori had various health problems, including heart and stomach issues, and cancer. He passed away from cancer in San Borja, Lima, on 11 September 2024, at the age of 86. His doctor stated he died due to complications from tongue cancer.

Legacy

Many Peruvians credit Fujimori with bringing stability to the country. He helped end the violence from rebel groups and fixed the economy after a period of very high inflation. The "Fujishock" economic changes brought short-term economic stability.

His economic policies led to significant changes. Businesses gained more influence. Peru rejoined the global economy and attracted foreign investment. Selling state-owned companies improved services like telephone and internet. For example, before these changes, it could take 10 years to get a phone line, but after, it only took a few days. The number of phone lines in Peru increased greatly. These changes also brought foreign investment in mining and energy projects.

Studies show that the number of Peruvians living in poverty decreased during Fujimori's time in office. Also, Peru reduced undernourishment by about 29% from the early to late 1990s.

See Also

In Spanish: Alberto Fujimori para niños

In Spanish: Alberto Fujimori para niños

- History of Peru

- Peruvian internal conflict

- Japanese Peruvians

- List of presidents of Peru

- Politics of Peru

- Vladimiro Montesinos

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |