History of Peru facts for kids

The history of Peru is a long and exciting journey that goes back over 15,000 years! It covers many stages of cultural growth along Peru's coast and in the Andes mountains. Peru's coast was home to the Norte Chico civilization, the oldest civilization in the Americas. It was one of the world's first major civilizations. When the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, Peru was the heartland of the powerful Inca Empire. This was the largest and most advanced state in the Americas before Europeans arrived. After the Spanish took over the Incas, the Spanish Empire created a Viceroyalty here. This new government ruled most of Spain's lands in South America. Peru declared independence from Spain in 1821. However, it truly became independent after the Battle of Ayacucho three years later.

Historians divide Peru's history into three main parts:

- The pre-Hispanic period: This goes from the first civilizations until the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

- The viceregal or colonial period: This runs from the Spanish conquest to Peru's declaration of independence.

- The republican period: This covers the time from the war of independence to today.

Contents

- Pre-Hispanic era

- Spanish era

- Republican era

- Early Republic (1824–1836)

- Peru-Bolivian Confederation (1836–1839)

- Restoration (1839–1841)

- Military Anarchy (1841–1845)

- The Guano Era (1845–1866)

- Economic and International Crisis (1866–1883)

- National Reconstruction (1884–1895)

- Aristocratic Republic (1895–1919)

- The Oncenio (1919–1930)

- Military Governments (1930–1939)

- Democratic Spring (1939–1948)

- The Ochenio (1948–1956)

- Moderate Civil Reform (1956–1968)

- Radical Military Reform (1968–1980)

- Terrorism and the Fujimorato (1980–2000)

- Business Republic (2000–2016)

- Political Crisis (2016–Present)

- See also

Pre-Hispanic era

Ancient Cultures of Peru

Tools for hunting from over 11,000 years ago have been found in caves. These include places like Pachacamac and Lauricocha. Some of the very first civilizations appeared around 6000 BC. They were in coastal areas like Chilca and Paracas. They also lived in highland areas like Callejón de Huaylas.

Over the next 3,000 years, people changed from moving around a lot to growing crops. This is seen at sites like Jiskairumoko and Huaca Prieta. They started growing plants like corn and cotton. They also tamed animals such as the wild ancestors of the llama, alpaca, and guinea pig. This is shown in 6000 BC paintings of Camelids in the Mollepunko caves. People learned to spin and knit cotton and wool. They also made baskets and pottery.

As people settled down, farming helped them build towns. New societies grew along the coast and in the Andes mountains. The first known city in the Americas was Caral. It is located in the Supe Valley, about 200 km north of Lima. It was built around 2500 BC.

The remains of this civilization, also called Norte Chico, include about 30 pyramid-shaped buildings. They were built with steps and had flat roofs. Some were as tall as 20 meters. Caral is seen as one of the world's first civilizations. It developed on its own, without influence from others.

In the early 2000s, archeologists found new signs of old, complex cultures. In 2005, Tom D. Dillehay found 5,400-year-old irrigation canals in the Zaña Valley. There might even be a 6,700-year-old one. This showed that farming improvements happened much earlier than thought.

In 2006, Robert Benfer found a 4,200-year-old observatory at Buena Vista. This site is in the Andes, north of Lima. They believe the observatory helped people understand seasons for farming. It has the oldest 3D sculptures found in South America. In 2007, archaeologist Walter Alva found a 4,000-year-old temple. It had painted murals at Ventarrón in the Lambayeque region. The temple contained gifts from jungle and coastal societies. These discoveries show that complex societies with big building projects existed much earlier in South America.

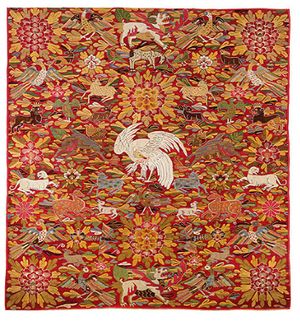

Many other civilizations grew and were taken over by stronger ones. These include Kotosh, Chavin, Paracas, Lima, Nasca, Moche, Tiwanaku, Wari, Lambayeque, Chimu, and Chincha. The Paracas culture appeared on the southern coast around 300 BC. They were known for using vicuña fibers, not just cotton, to make fine textiles. This was an advanced technique. Coastal cultures like the Moche and Nazca thrived from about 100 BC to AD 700. The Moche made amazing metalwork and beautiful pottery. The Nazca are famous for their textiles and the mysterious Nazca lines.

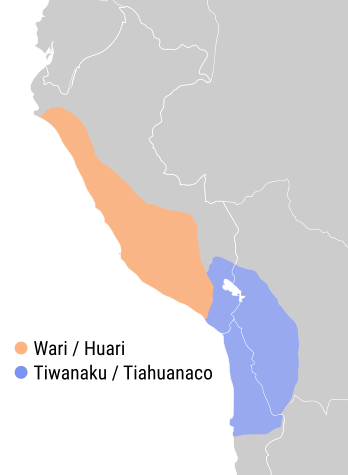

These coastal cultures eventually weakened due to floods and droughts. Then, the Huari and Tiwanaku cultures, who lived inland in the Andes, became powerful. They controlled much of modern-day Peru and Bolivia. Later, strong city-states like Chancay, Sipan, and Cajamarca emerged. Two empires, Chimor and Chachapoyas, also rose. These cultures developed advanced ways of farming, working with gold and silver, making pottery, metal objects, and knitting. Around 700 BC, they seemed to have social systems that were like early versions of the Inca civilization.

In the highlands, the Tiahuanaco culture near Lake Titicaca and the Wari culture near Ayacucho grew into large cities. They also developed wide-ranging state systems between 500 and 1000 AD.

In the Amazon rainforest, discoveries from the Chachapoya and Wari cultures show complex societies existed there. This was before the Inca Empire took over the Amazonas region.

As the Inca Empire grew, it defeated and absorbed Andean cultures that didn't cooperate. This included the Chachapoyas culture.

In September 2021, archaeologists found eight 800-year-old bodies near Chilca. The bodies, including adults and children, were wrapped in plants before burial. Some dishes and musical instruments were also found. Researchers believe these remains belong to the Chilca culture. This culture was different from other ancient groups in the area.

The Inca Empire (1438–1532)

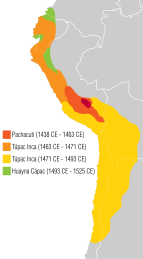

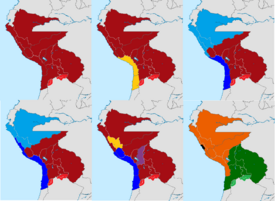

The Incas built the largest and most advanced empire in the Americas before Columbus. It was called the Tahuantinsuyo, which means "The Four United Regions" in Quechua. It reached its biggest size in the early 1500s. It covered parts of Ecuador, Colombia, most of Peru, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina. From east to west, it stretched from Bolivia to the Amazonian forests.

The empire started with a tribe in Cusco, which became the capital. Pachacutec was not the first Inca ruler, but he was the first to greatly expand the Cusco state. His descendants later ruled the empire. They did this through both invasions and peaceful agreements, like marriages between rulers.

In Cuzco, the royal city was shaped like a cougar. The head, the main royal building, is now known as Sacsayhuamán. Cusco was the empire's center for government, politics, and military. The empire was divided into four parts: Chinchaysuyu, Antisuyu, Kuntisuyu, and Qullasuyu.

The official language was Quechua. Conquered people could keep their religions and ways of life. However, they had to accept Inca culture as superior. Inti, the sun god, was one of the most important gods. The Inca (Emperor) was seen as Inti's representative on Earth.

The Tawantinsuyu had a structured society with the Inca as the ruler. Its economy was based on shared land ownership. The large empire also had an amazing system of roads called the Inca Trail. Chasquis, who were message carriers, used these roads to deliver information across the empire to Cusco.

Machu Picchu (meaning "old peak" in Quechua) is a well-preserved Inca ruin. It sits on a high mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley, about 70 km northwest of Cusco. Its elevation is about 2,350 meters. It was forgotten by the outside world for centuries. Then, Yale archaeologist Hiram Bingham III "rediscovered" it in 1911. His book Lost City of the Incas made it famous worldwide. Peru is trying to get back thousands of artifacts that Bingham took from the site.

Peru has many other well-preserved Inca ruins besides Machu Picchu. Much of the Inca architecture and stonework still puzzles archaeologists. For example, at Sacsaywaman in Cusco, the zig-zag walls are made of huge boulders. They fit together perfectly without mortar. They have stayed strong for centuries, even surviving earthquakes. Damage seen today was mostly from battles between the Spanish and Incas, and later from people taking stones for new buildings. It's still a mystery how the Incas shaped, lifted, and fitted these massive stones. It's also unknown how they moved the stones to the site, as they are not from the local area.

Spanish era

Spanish Conquest (1532–1572)

| Where did the name Peru come from? The word Peru might come from Birú. This was the name of a local ruler near the Bay of San Miguel, Panama, in the early 1500s. When Spanish explorers visited his lands in 1522, they were the southernmost part of the New World known to Europeans. So, when Francisco Pizarro explored lands further south, they were called Birú or Peru.

Another story comes from Inca Garcilasco de la Vega. He was the son of an Inca princess and a Spanish conqueror. He said the name Birú came from a common Indian met by a ship's crew. This ship was exploring for Governor Pedro Arias de Ávila. Garcilasco also wrote about many misunderstandings due to not having a common language. The Spanish Crown made the name official in 1529. The Capitulación de Toledo named the newly found Inca Empire as the province of Peru. Under Spanish rule, the country was called the Viceroyalty of Peru. After independence, it became the Republic of Peru. |

When the Spanish arrived in 1531, Peru was the center of the advanced Inca civilization. The Inca Empire, based in Cuzco, stretched from southwest Ecuador to northern Chile.

Francisco Pizarro and his brothers heard about a rich kingdom. In 1532, they arrived in the land they called Peru. Before the Spanish conquerors, smallpox had already spread through the Inca Empire. This disease came from the Spanish in Panama. Smallpox killed the Inca ruler Huayna Capac and most of his family, including his heir. This caused the Inca political system to fall apart. It also led to a civil war between brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar.

Pizarro took advantage of this situation. On November 16, 1532, Atahualpa's army was celebrating unarmed in Cajamarca. The Spanish tricked Atahualpa into a trap during the Battle of Cajamarca. The 168 well-armed Spaniards killed thousands of Inca soldiers. They captured the new Inca ruler, causing great fear among the natives. When Huáscar was killed, the Spanish accused Atahualpa of the murder. They then executed him.

For a while, Pizarro pretended to respect the Inca authority. He recognized Túpac Huallpa as the new Sapa Inca after Atahualpa's death. But the conquerors' bad actions made this trick obvious. Spanish rule became stronger as native rebellions were violently stopped. By March 23, 1534, Pizarro and the Spanish had rebuilt Cuzco as a Spanish colonial town.

Creating a stable colonial government took time. There were native revolts and fights among the Conquistadores (led by Pizarro and Diego de Almagro). A long civil war happened, and Pizarro won at the Battle of Las Salinas. In 1541, Pizarro was killed by a group led by Diego de Almagro II. This shook the stability of the new colonial government.

Despite these problems, the Spanish continued to colonize. A major step was founding Lima in January 1535. From Lima, they set up political and administrative systems. The new rulers created the encomienda system. Through this, the Spanish collected tribute from local people. Part of this was sent to Seville in exchange for converting natives to Christianity. The land itself still belonged to the king of Spain. As governor, Pizarro used the encomienda system to give his soldiers almost unlimited power over groups of native Peruvians. This created the colonial land ownership system. Native Peruvians were now expected to raise Old World animals and crops for their landlords. Resistance was severely punished.

To strengthen Spanish royal power, a Real Audiencia (Royal Court) was created. In 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru (Virreinato del Perú) was established. It ruled most of Spanish South America. (Colombia, Ecuador, Panamá, and Venezuela became the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay became the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776).

After Pizarro's death, there were many internal problems. Spain sent Blasco Núñez Vela to be Peru's first viceroy in 1544. Pizarro's brother, Gonzalo Pizarro, later killed him. But a new viceroy, Pedro de la Gasca, eventually brought order. He captured and executed Gonzalo Pizarro.

A census by the last Quipucamayoc said there were 12 million people in Inca Peru. Forty-five years later, under Viceroy Toledo, the number was only 1.1 million. Historian David N. Cook thinks the population dropped from 9 million in the 1520s to about 600,000 in 1620. This was mainly due to infectious diseases. While it wasn't an organized attempt to kill people, the results were similar. Scholars now believe that diseases like smallpox were the main cause of the population decline. Unlike the Spanish, Amerindians had no immunity to these diseases. Inca cities were given Spanish Christian names and rebuilt around a central square with a church. Some Inca cities, like Cuzco, kept native stone foundations for their walls. Other Inca sites, like Huanuco Viejo, were abandoned for lower, more Spanish-friendly cities.

Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

In 1542, the Spanish Crown created the Viceroyalty of Peru. It was reorganized when Viceroy Francisco de Toledo arrived in 1572. He ended the native Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba and executed Tupac Amaru I. He also focused on making money through trade control and mining. Silver from the mines of Potosí was especially important. He brought back the Inca mita, a forced labor system. This made native communities work in the mines. This organization made Peru the main source of Spanish wealth and power in South America.

The city of Lima, founded by Pizarro in 1535 as "Ciudad de Reyes" (City of Kings), became the capital of the new viceroyalty. It grew into a powerful city, ruling most of Spanish South America. Precious metals passed through Lima on their way to the Isthmus of Panama and then to Seville, Spain. For the Pacific route, they went to Mexico, then from Acapulco to the Philippines. By the 1700s, Lima was a grand and noble colonial capital. It had a university and was the main Spanish stronghold in the Americas. Peru was rich and had many people. Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera, governor of Panama, settled Zamboanga City in the Philippines. He used soldiers and colonists from Peru.

However, in the 1700s, the Spanish did not have complete control far from Lima. They needed help from local leaders to govern the provinces. These local leaders, called Curacas, were proud of their Inca history. Also, throughout the 1700s, native people rebelled against the Spanish. Two important rebellions were led by Juan Santos Atahualpa in 1742 and Túpac Amaru II in 1780. Juan Santos Atahualpa's rebellion in the jungle provinces of Tarma and Jauja drove the Spanish out of a large area. Tupac Amaru II's rebellion was in the highlands near Cuzco.

At this time, an economic problem was growing. New viceroyalties were created, taking land from Peru. Trade centers moved from Lima to Caracas and Buenos Aires. Mining and textile production also decreased. This crisis helped the native rebellion of Túpac Amaru II. It also led to the slow decline of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain and captured King Ferdinand VII. Later, in 1812, the Cadíz Cortes (Spain's assembly) passed a liberal Constitution. These events inspired ideas of freedom among the Spanish Criollo people (people of Spanish descent born in America) across Spanish America. In Peru, Criollo rebellions happened in Huánuco in 1812 and Cuzco between 1814 and 1816. Despite these, the Criollo elite in Peru mostly stayed loyal to Spain. This is why the Viceroyalty of Peru became the last place where Spain held power in South America.

Wars for Independence (1811–1824)

Peru's fight for independence began with an uprising led by José de San Martín from Argentina and Simón Bolívar from Venezuela. San Martín had defeated the Spanish loyalists in Chile. He landed in Paracas in 1819. He led a military campaign with 4,200 soldiers. This expedition, including warships, was organized and paid for by Chile. It sailed from Valparaíso in August 1820. San Martín declared Peru's independence in Lima on July 28, 1821. He said, "... From this moment on, Peru is free and independent, by the general will of the people and the justice of its cause that God defends. Long live the homeland! Long live freedom! Long live our independence!" San Martín was named "Protector of Peruvian Freedom" in August 1821 after partly freeing Peru from the Spanish.

On July 26 and 27, 1822, Bolívar met with San Martín at the Guayaquil Conference. They tried to decide Peru's political future. San Martín wanted a king with a constitution, while Bolivar preferred a republic. However, both agreed Peru should be independent from Spain. After the meeting, San Martín left Peru on September 22, 1822. He left the entire independence movement to Simon Bolivar.

The Peruvian congress made Bolivar dictator of Peru on February 10, 1824. This allowed him to completely reorganize the government and military. With the help of General Antonio José de Sucre, Bolívar decisively defeated the Spanish cavalry at the Battle of Junín on August 6, 1824. Sucre then destroyed the remaining Spanish forces at Ayacucho on December 9, 1824. The war finally ended when the last Spanish loyalists surrendered the Real Felipe Fortress in 1826.

This victory brought political independence. However, some native and mestizo people still supported the monarchy. In Huanta Province, they rebelled from 1825–28. This was known as the war of the punas or the Huanta Rebellion.

Spain tried to regain its former colonies, like in the Battle of Callao (1866). But these attempts failed. Spain finally recognized Peruvian independence in 1879.

Republican era

The republican era of Peru generally starts after the declaration of independence or the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824. Its periods are based on Jorge Basadre's work, Historia de la República del Perú.

Early Republic (1824–1836)

Quick facts for kids

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1822–1836 | |||||||||

|

Flag (1825–1884)

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1823

|

José de la Riva Agüero (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1836

|

Luis José de Orbegoso (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| July 26, 1822 | |||||||||

|

• Confederation established

|

October 28, 1836 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

After the Battle of Ayacucho, Spanish General José de Canterac signed the final surrender of the Royalist Army in Peru. Even though Spain surrendered, relations between Peru and Spain were not established until 1879. During this time, the First Militarism began in 1827. This was a period when several military leaders controlled the country, starting with José de La Mar's presidency.

Spanish Resistance

When the surrender was signed, Spanish loyalist forces still held the southern provinces. They slowly gave up to the rebels. Despite the apparent end of the successful patriot campaigns, two Spanish leaders refused to accept the surrender. These were José Ramón Rodil in Callao and Pedro Antonio Olañeta in Upper Peru. Also, a resistance group in Ayacucho, led by Antonio Huachaca, continued fighting until 1839.

Olañeta, based in Potosí, became the target of a campaign led by Antonio José de Sucre. This campaign began in January and ended in April 1825. Olañeta was fatally wounded at the Battle of Tumusla on April 1 and died the next day.

Rodil, on the other hand, stayed in the Real Felipe Fortress at the port of Callao, near Lima. He was waiting for Spanish reinforcements that never came. The capital city itself had been retaken by Royalist troops. But then, reinforcements arrived for the Patriot side. This led to Rodil's forces being surrounded from December 5, 1824, to January 23, 1826. This became the last Spanish stronghold in South America. The bad conditions in the fortress eventually forced Rodil and his forces to surrender.

Bolivar's Influence

Simón Bolívar became dictator of Peru on January 17, 1824. He told the Constituent Congress he wanted to resign, but they didn't accept. Instead, his term was extended until 1827. During this time, he traveled to southern and Upper Peru. The final flag and coat of arms of Peru were established on February 25, 1825.

Upper Peru was divided on whether to join Peru or the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Soon, a new idea emerged: the region should become an independent state. The State of Upper Peru was established as an independent state, later becoming Bolivia. Bolívar helped write the constitutions for Bolivia, Peru, and later Gran Colombia. The similar constitutions showed his wish to create a federation in America. This led to the Congress of Panama and later to anti-Bolívar feelings. He left Peru on September 3, 1826. A year later, the Constituent Congress was dissolved.

Conflicts with Neighbors

José de La Mar became president of Peru on August 22, 1827. He was chosen by the new Congress. Under his rule, Peru went to war with Bolivia and Colombia. Peru felt at a disadvantage because it was surrounded by countries influenced by Bolívar.

A Peruvian invasion of Bolivia led by Agustín Gamarra began on May 1, 1828. The Peruvian Army quickly took over the Bolivian department of La Paz. They set up a pro-Peruvian government. They also successfully sent Colombian troops out of Bolivia using ships paid for by Bolivia. These ships left from the Peruvian port of Arica.

The events in Bolivia led to a war between Peru and Colombia. It ended with the Battle of Tarqui on February 27, 1829. After this, a ceasefire was signed. Breaking the ceasefire almost led to more war. But political problems in Peru prevented it. Agustín Gamarra removed La Mar from power. Gamarra then signed a peace treaty with Colombia.

Later Instability

A civil war broke out in 1834. Revolutionaries opposed Orbegoso as Gamarra's successor. Orbegoso was popular with the people. The revolution was eventually stopped. Orbegoso, who had been in the Real Felipe Fortress, returned to Lima on May 3, 1834.

The desire to unite lower and upper Peru led to the Salaverry-Santa Cruz War. This war resulted in the creation of the Republic of South Peru on March 17, 1836. The Republic of North Peru was formed on August 11, 1836. Andrés de Santa Cruz named himself the Supreme Protector of both states. These states later formed the Peru–Bolivian Confederation.

Peru-Bolivian Confederation (1836–1839)

The creation of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation quickly led to war. Peruvian exiles, along with neighboring Chile and Argentina, were against this new state.

Peruvian opposition led to the War of the Confederation. This included North Peru breaking away. Its president, Luis de Orbegoso, formed the Restoration Army of Peru, but it was defeated at the Battle of Guías. Peruvian exiles in Chile also formed the United Restoration Army. They fought against the confederation until their defeat in the Battle of Yungay, which led to its end.

The conflict against the confederation also had a southern part, called the War of Tarija. This was a fight between Argentina and the Confederation over the territory of Tarija. Argentina took the territory during the war, but it was returned to Bolivia in March 1839.

Besides the conflict in Tarija, the Second Iquicha War also began. This ended the royalist self-rule that had seen conflict a decade earlier. Huachaca, who led this group, fled to the Apurímac jungle. He chose to stay there, calling the republicans "antichrists."

Restoration (1839–1841)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1839–1841 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1839–1841

|

Agustín Gamarra | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Peru–Bolivia dissolved

|

August 25, 1839 | ||||||||

|

• Battle of Ingavi

|

November 18, 1841 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

After the Peru-Bolivian Confederation ended, Peru and Bolivia became independent countries again. The Congress in Huancayo confirmed Agustín Gamarra as Provisional President on August 15, 1839. This was while a new Constitution was being written. Once approved, and after an election, Gamarra became the official President of Peru on July 10, 1840.

During his second time as president, Gamarra signed agreements with Brazil. The Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe school opened, and the newspaper El Comercio started in 1839. Gamarra ruled in a strong and traditional way, as needed after years of civil war. He worked to bring peace to the country. He faced a rebellion led by Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco in Arequipa in January 1841. Vivanco declared himself Supreme Chief. To fight him, Gamarra sent his war minister, Ramón Castilla. Castilla won against Vivanco's forces in Cuevillas after an initial defeat. Vivanco then fled to Bolivia.

Gamarra wanted to unite Bolivia and Peru. This led to an attempt to take over Bolivia, but it failed. It turned into a long war. After reaching La Paz without resistance, Gamarra fought in the Battle of Ingavi. He was killed there. After this battle, Bolivia occupied southern Peru. But Peruvian resistance grew, leading to a successful counterattack. This was helped by the small number of Bolivian troops.

The two nations signed the Treaty of Puno on June 7, 1842. This officially ended the war. Both countries agreed to remain separate sovereign states. Bolivian troops left Peruvian territory eight days later. Bolivia gave up all claims to southern Peruvian land. However, the treaty did not solve the border problem or the idea of uniting the two states.

The conflict ended with things returning to how they were before the war. Despite this, Peruvian history books say that the victories on Peruvian soil made up for the defeat at Ingavi. This left Peru in a better position after the war.

Military Anarchy (1841–1845)

After Gamarra's death, Manuel Menéndez was recognized as temporary president. However, several military leaders fought for power. In the north was Juan Crisóstomo Torrico. In the south were Antonio Gutiérrez de La Fuente, Domingo Nieto, and Juan Francisco de Vidal. In Arequipa was Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco. Menéndez could not keep power and was removed by Torrico.

This chaos led to the Peruvian Civil War of 1843–1844. By then, Vivanco had set up a government called the Directory. A rebellion led by Domingo Nieto also tried to form a legitimate government. On September 3, 1843, the revolutionaries created a Provisional Government Junta of the Free Departments in Cuzco. Domingo Nieto became its president. After his death in 1844, Castilla took over.

The civil war ended at the Battle of Carmen Alto on July 22, 1844. This battle was between Vivanco's and Castilla's troops near Arequipa. After Vivanco's troops were defeated, Vivanco himself arrived in Callao on July 27. He was arrested by the Prefect of Lima, Domingo Elías, and sent away to Chile a few days later. With Castilla as the new leader, the period of chaos ended.

The Guano Era (1845–1866)

After Castilla became president, Peru entered a time of peace and economic growth. The period of chaos had ended. Peru also had a near-total control over the trade of guano (bird droppings used as fertilizer). This allowed the government to pay off its foreign debt. This earned Peru respect in the international economy. Several changes were made, including in education. The economy continued to grow until the 1860s.

Castilla was replaced by his advisor José Rufino Echenique in 1851. Echenique continued Castilla's work, and the economy kept growing. His government was traditional, which eventually led to conflict with more liberal groups. On October 23, 1851, Peru signed its first border treaty with Brazil. Peru gave up land in the Amazon rainforest that Ecuador also claimed.

Liberal Revolution (1854–1855)

Echenique was accused of corruption by his opponents. Some pointed to a lavish party hosted by his wife, Victoria Tristán, as proof of his wasteful spending. This seemed like an insult to the country's widespread poverty. Others, like Domingo Elías, accused Echenique of being "too generous" in paying the country's foreign debt. As conflict grew between the traditional government and the liberal opposition, the Liberal Revolution of 1854 broke out. The liberals, soon led by Castilla, defeated the government at the Battle of La Palma. Castilla was then made president again.

Castilla called for a National Convention. Its members were chosen by direct and universal vote. It met on July 14, 1855. This Convention wrote the Liberal Constitution of 1856. Conservatives were unhappy with the liberal government. They rose up in Arequipa, led by Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco, an old rival of Castilla. A bloody civil war began. It ended with Castilla's victory after the capture of Arequipa on March 7, 1858.

War with Ecuador (1857–1860)

Between 1857 and 1860, a war broke out against Ecuador. This was over disputed territories in the Amazon. Ecuador had supposedly sold these lands to British companies to pay its foreign debt. Peru's victory in the war prevented Ecuador from claiming these areas.

War with Spain

In 1865, a civil war began. It was fought by forces led by Colonel Mariano Ignacio Prado against President Juan Antonio Pezet's government. This was because Pezet was seen as weak in dealing with Spain's occupation of the Chincha Islands. Specifically, it was due to the signing of the Vivanco–Pareja Treaty. As a result, Pezet was overthrown. Prado then formed an alliance against Spain with Chile, Bolivia, and Ecuador. He also declared war on Spain. On May 2, 1866, the Battle of Callao took place. A peace treaty was signed in 1879. The costs of the war severely hurt Peru's economy, which began to decline.

Economic and International Crisis (1866–1883)

With Prado as provisional and then official president, a new constitution was adopted. Its very liberal nature led to a civil war. This war was led by Pedro Diez Canseco and José Balta. It ended Prado's presidency and brought back the 1860 constitution.

The new Balta government appointed a young Nicolás de Piérola as Minister of Economy. He signed a deal with the Jewish-French businessman Auguste Dreyfus. Dreyfus's company paid Peru two million soles upfront. It also agreed to pay 700,000 soles each month and cover the interest on Peru's foreign debt.

With money from the Dreyfus contract, Peru started building many railroads. The American businessman Henry Meiggs built a standard gauge line from Callao across the Andes to Huancayo. He controlled its politics for a while. In the end, he went bankrupt and so did the country. Financial problems forced the government to take over in 1874. Working conditions were difficult. There were conflicts due to different skill levels and organization among North Americans, Europeans, Blacks, and Chinese workers. Conditions were very harsh for the Chinese, leading to strikes and violent suppression.

Elections were held in 1872. Manuel Pardo of the Civilista Party was elected as Peru's first civilian president. Many military members were upset by a civilian government. They thought they would lose their special rights. Among those worried were the Gutiérrez brothers from Huancarqui. The brothers, led by Colonel Tomás Gutiérrez, staged a coup d'état against Balta on July 22, 1872. The new government lasted only until the 26th. The brothers were overthrown, three were killed, and only one survived.

Pardo became president on August 2, ending the First Militarism that had been in place since 1827. Under his government, the Treaty of Defensive Alliance was signed with Bolivia. This treaty would lead Peru to fight against Chile seven years later.

War of the Pacific

In 1879, Peru entered the War of the Pacific. This happened after Bolivia asked Peru for help against Chile, based on their alliance. The Peruvian Government tried to solve the problem peacefully. They sent a diplomatic team to talk with the Chilean government. But the team concluded that war was unavoidable. On March 14, 1879, Bolivia declared war. Chile responded by declaring war on Bolivia and Peru on April 5, 1879. Peru then declared war the next day.

Chile's land campaigns in Tarapacá, Tacna and Arica, Lima, and Breña led to Chile taking control of these areas. These territories were governed from occupied Lima. At the same time, a government that worked with Chile was set up in Lima. This government was initially based in La Magdalena, and then in Cajamarca. The Peruvian Resistance fought against this government in the mountains. Chile's naval campaign was also very important. It allowed attacks on Peru's northern coast. A notable figure from this campaign, respected by both Peruvians and Chileans, was Miguel Grau. He was killed in action during the Battle of Angamos. His ship, the Huáscar, was captured by the Chilean Navy.

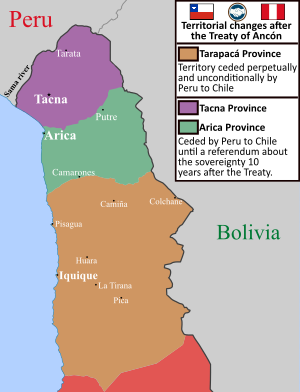

The war reached its peak after the Battle of Tacna. This battle effectively broke the alliance between Peru and Bolivia. It ended with a Chilean victory over Peru and Bolivia. Peru's government in Lima signed the Treaty of Ancón in 1883. In this treaty, the Department of Tarapacá was given to Chile. The future of the provinces of Tacna and Arica was to be decided by a vote ten years later. However, this vote never happened.

The issue of Tacna and Arica became the Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute. Bolivia's reaction to losing its Litoral Department, and thus its access to the sea, became the Bolivian–Chilean territorial dispute. This is remembered annually on Día del Mar.

National Reconstruction (1884–1895)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884–1895 | |||||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

|

• 1883–1885

|

Miguel Iglesias (first) | ||||||||||

|

• 1895–1899

|

Nicolás de Piérola (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Civil war begins

|

August 27, 1884 | ||||||||||

|

• De Piérola presidency begins

|

September 8, 1895 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

After the War of the Pacific, a huge effort to rebuild began. Military leaders took control of the government again. This was because civilian leaders were seen as weak during constant wars. This period was called the Second Militarism. Unlike the first period, these military leaders returned to politics not as heroes, but as those who had been defeated. The government started social and economic changes to recover from the war's damage.

During this time, the occupied provinces of Tacna and Arica underwent "Chilenization". This meant promoting Chilean culture to replace Peruvian culture. Groups called Patriotic Leagues were formed to encourage Peruvians to leave. Chilean families also started moving to the region. Those who left Peru settled mainly in Callao. Some also joined a colonization project in Loreto. This was to counter Colombian claims over the region. They established settlements like Puerto Arica and Tarapacá. After the Salomón–Lozano Treaty in 1922, these settlements were given to Colombia. Some settlers moved back to Peru, creating new towns like Nuevo Tarapacá and Puerto Arica.

Because Iglesias brought back the native tribute and landowners abused native people, a rebellion began in Huaraz on March 1, 1885. It was led by Pedro Pablo Atusparía. The conflict ended only in 1887.

Iglesias and Cáceres Conflict

Miguel Iglesias's Regenerator Government had been set up under Chilean occupation. It signed the Treaty of Ancón and continued as Peru's official government. During this time, Andrés Avelino Cáceres, who fought in the Breña campaign and was known as the Hero of Breña, opposed Iglesias. Cáceres had more popular support than Iglesias's government.

Iglesias tried to get Cáceres's support through talks. But negotiations failed, and Iglesias demanded Cáceres's full surrender. Cáceres then declared himself President on July 16, 1884. He argued that the constitutional order had broken down. This disagreement led to the Peruvian Civil War of 1884–1885.

Iglesias's and Cáceres's forces first clashed in Lima and later in Trujillo. After defeats on the north coast, Cáceres moved to the south-central region. He went to Cuzco, Arequipa, Apurímac, and Ayacucho. There, he rebuilt his army to attack again. He ordered his troops to pretend to be defeated near Jauja. Meanwhile, he moved his best troops to Huaripampa. They cut off bridges that Iglesias's troops would have used to return. Then, they moved to Lima and successfully attacked Iglesias. This ended the civil war. Iglesias was sent away to Spain. He only returned in 1895 after being elected senator for Cajamarca. He died in 1909.

Cáceres and de Piérola Conflict

Cáceres became president for the second time on August 10, 1894. But he lacked public support. Anti-Cáceres groups formed the National Coalition, made of democrats and civilian supporters. They chose Nicolás de Piérola as their leader. Piérola was living away in Chile at the time. Across Peru, groups of Montoneros (guerrilla fighters) joined the Coalition's cause. Piérola returned to Peru, landing in Puerto Caballas, in Ica. He went to Chincha, where he gave a speech to the nation. He took the title of National Delegate and immediately campaigned in Lima, leading the Montoneros. They attacked the capital from March 17 to 19, 1895. Cáceres saw that the people were supporting the coalition. He resigned and went into exile.

A Government Board was set up after Piérola's Montoneros won in Lima and Cáceres left. Manuel Candamo was elected president of this Board, though he wasn't a member. He took charge of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He served for six months, from March 20 to September 8, 1895. Then, he handed power to Piérola, who won the elections. After a short time when the military again controlled the country, civilian rule was permanently established with Piérola's election in 1895. His second term ended successfully in 1899. It was marked by his efforts to rebuild Peru, which had been devastated. He started financial, military, religious, and civil reforms. With the country in a fragile state, political stability was achieved only in the early 1900s.

Aristocratic Republic (1895–1919)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895–1919 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1895–1899

|

Nicolás de Piérola (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1915–1919

|

José Pardo (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• De Piérola presidency begins

|

September 8, 1895 | ||||||||

| July 4, 1919 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

With de Piérola elected president, Peru began its "Aristocratic Republic" period. It was called this because most presidents during this time came from the country's wealthy elite.

Peru became more economically dependent on English and American businesses. New economic activities grew, such as farming for export (sugar and cotton), rubber extraction, and oil extraction. However, the country did not become industrialized. This was because the focus was on making money from raw materials. This increased discrimination and exploitation of native peoples through forced labor systems. One example was the Putumayo genocide during the Amazon rubber boom. The unhappiness of the common people led to the rise of labor movements and strikes.

This period saw its first conflicts in 1896. Separatists in Loreto revolted against the government. They broke away from Peru and formed the short-lived Federal State of Loreto. The government sent troops to stop the uprising, which they did. A few years later, Colonel Emilio Vizcarra, the Prefect of Loreto, also broke away from Peru. He declared the Jungle Republic. This was an unrecognized state whose borders matched the Loreto Department. President Eduardo López de Romaña immediately sent troops. The state ceased to exist in 1900.

Another conflict happened in Huanta. This was due to new rules, including a salt tax and a ban on Bolivian money. Veterans from earlier conflicts, like the Breña campaign and the 1884–85 civil war, were among the participants.

Territorial Disputes

Augusto B. Leguía's first time as president happened during this period. He faced border disputes with all of Peru's neighbors. Only the disputes with Brazil and Bolivia were settled in September 1909. Small fights occurred in 1910 with Ecuador and in 1911 with Colombia. The latter became known as the La Pedrera conflict. Relations with Chile were broken because Chile continued its "Chilenization" policies in Tacna and Arica.

Leguía also faced internal conflict. This included an attempted coup in 1909 by Nicolás de Piérola's brother, Carlos, and his children. Leguía left the Civilista Party, which then split into two groups: those loyal to Pardo and those loyal to Leguía. In the last two years of his government, a severe economic crisis began. This was caused by fast-growing national debt, defense spending, and a budget deficit.

Guillermo Billinghurst wanted to help the working class. This made conservative groups oppose him. He had a tough fight with Congress, which was controlled by his political enemies. He proposed dissolving parliament and letting the people make big changes to the constitution. This led to a military uprising by Colonel Óscar R. Benavides. Benavides, known as the hero of La Pedrera, overthrew Billinghurst on February 4, 1914.

After taking control, Benavides dealt with money problems. He promised to restore legal order. In 1915, he called a meeting of the civilist, liberal, and constitutional parties. They chose former president José Pardo y Barreda as their unified candidate. Pardo won the elections easily that year, defeating Carlos de Piérola.

José Pardo's second government was marked by political and social unrest. This was a sign of the weakening of civilian society and a global crisis. Because of World War I, the economic situation for workers got worse. This set the stage for labor unions to grow. There were many strikes demanding lower prices and an "8-hour workday." The 8-hour workday was finally granted on January 15, 1919. In the southern Andes, landowners abused native and peasant people. This led to many native uprisings, like the one in 1915 led by Teodomiro Gutiérrez Cuevas.

Pardo called for elections in 1919. Former president Augusto B. Leguía ran against the official candidate, Ántero Aspíllaga. The elections were not considered very fair. Leguía was declared the winner, but many votes were cancelled in the official count. Leguía and his supporters feared the elections would be cancelled. They worried that the decision would go to Congress, where the civilistas had more power. So, they staged a coup with the gendarmerie's help on July 4, 1919. This ended the "Aristocratic Republic" and began Leguía's Oncenio.

The Oncenio (1919–1930)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919–1930 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1919–1930

|

Augusto B. Leguía | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| July 4, 1919 | |||||||||

|

• Coup d'état

|

August 25, 1930 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

As with his earlier government, American money flowed into Peru. The wealthy class benefited. This policy, along with more reliance on foreign investment, made progressive groups in Peru oppose the rich landowners.

Leguía's presidency happened during Peru's 100-year independence celebrations on July 28, 1921. More celebrations took place in 1924 for the Battle of Ayacucho.

Territorial Disputes

A final peace treaty was signed between Peru and Chile in 1929. It was called the Treaty of Lima. According to the treaty, Tacna returned to Peru. Peru permanently gave up the provinces of Arica and Tarapacá. However, Peru kept some rights to port activities in Arica. There were also rules about what Chile could do in those territories. The treaty was debated in Peru. But it largely ended the Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute.

In 1921, Peruvian captain Guillermo Cervantes declared the Federal State of Loreto. This region acted as if it were independent. The rebel leaders allowed special cardboard banknotes to be used as money. Local ports were closed, and trade was tightly controlled. The local people quickly accepted the revolution. But Peru's president Augusto Leguía reacted negatively. He sent troops to the area and stopped trade to the region. The local fighters were militarily weaker. By early 1922, a hungry Iquitos was taken over by Peruvian troops. Cervantes escaped on January 9 and found safety in the Ecuadorian jungle. His army became just a small group of rebels.

In 1922, another treaty, the Salomón–Lozano Treaty, was signed between Peru and Colombia. The United States helped mediate. A large amount of territory was given to Colombia, giving them access to the Amazon river. This further reduced Peru's land, except for a small area in Sucumbíos. This treaty was also controversial, especially in Loreto. Protests happened, and local unhappiness eventually led to the Leticia Incident in 1932. However, the treaty also ended the Colombian–Peruvian territorial dispute, although Ecuador also disputed it.

In 1924, Peruvian university reform leaders, forced to leave Peru by the government, founded the American People's Revolutionary Alliance (ARPA) in Mexico. This group greatly influenced Peru's political life. APRA grew from university reform and workers' struggles from 1918–1920. It was influenced by the Mexican revolution and its 1917 Constitution. It focused on issues like land reform and native rights. It was also somewhat influenced by the Russian revolution. It was close to Marxism, but differed on class struggle and the importance of Latin American unity.

In 1928, the Peruvian Socialist Party was founded. It was notably led by José Carlos Mariátegui, who had been a member of APRA. Shortly after, in 1929, the party created the General Confederation of Workers.

After the worldwide crisis of 1929, many short-lived governments followed. The APRA party had a chance to make big changes through political actions, but it didn't succeed. This was a nationalist movement, popular with the people and against foreign control. It was led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre in 1924. The Socialist Party of Peru, later the Peruvian Communist Party, was created four years later. It was led by José Carlos Mariátegui.

This period ended after a coup d'état by Lieutenant colonel Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro and his supporters. General Manuel María Ponce Brousset was interim President for two days. Then Sánchez Cerro returned to Lima from Arequipa.

Military Governments (1930–1939)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930–1939 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under a military government | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1930

|

Manuel M. Ponce (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1933–1939

|

Óscar R. Benavides (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Military coup d'etat

|

August 27, 1930 | ||||||||

|

• Trujillo revolt

|

1932 | ||||||||

|

• War with Colombia

|

1932–1933 | ||||||||

|

• "Status quo" border established

|

1936 | ||||||||

|

• Failed coup d'état

|

February 19, 1939 | ||||||||

|

• General election

|

October 22, 1939 | ||||||||

| December 8, 1939 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

With Leguía overthrown, Peru entered its Third Militarism. Military leaders again took control of the government. A military council was formed. Manuel María Ponce Brousset was the first president, followed by the more popular Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro. Sánchez Cerro was the first Peruvian President with Indigenous Peruvian ancestry. It was also rumored he had Afro-Peruvian Malagasy descent. Other big changes during this time were the rise of organized groups in politics and the growth of the middle class.

Sánchez Cerro called for elections while in power, planning to run himself. This led to a revolt in Arequipa, forcing Sánchez Cerro to resign. The Archbishop of Lima, Monsignor Mariano Holguín, took over the council on April 1, 1931. After a few hours, Holguín gave power to Leoncio Elías. Elías called a meeting where it was agreed that David Samanez Ocampo would be the new head of state. But this didn't happen because he was overthrown by Gustavo Jiménez. Samanez Ocampo, chosen for his popularity, became president on March 11, 1931. He called for elections on October 11 of the same year. Sánchez Cerro was elected president of Peru.

Sánchez Cerro's government was opposed by the left-wing American Popular Revolutionary Alliance. As a result, political repression was harsh in the early 1930s. Tens of thousands of Apristas (APRA members) were executed or imprisoned. A revolt in Trujillo was brutally stopped, serving as an example.

This period also saw a sudden increase in population and urbanization. By the 1940 census, which used racial categories, mestizos (people of mixed European and Indigenous descent) were grouped with whites. Together, they made up over 53% of the population. Mestizos likely outnumbered indigenous peoples and were the largest group.

Under Sánchez Cerro's constitutional government, a new constitution was adopted. Projects like building the Carretera Central (which connected Lima with La Oroya, Tarma, and La Merced) took place. There was also investment in the Peruvian Armed Forces. This was important because all three branches of the Armed Forces would soon be involved in the conflict with Colombia, which became an armed conflict in September 1932.

Conflict with Colombia

Sánchez Cerro's foreign policy initially aimed to respect existing border treaties. However, public opposition to the Salomón–Lozano Treaty led to a civilian takeover of the port town of Leticia. The government eventually supported this. The event caused protests in Colombia and started the Colombia–Peru War on September 1, 1932.

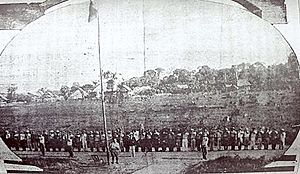

On April 30, 1933, Sánchez Cerro was killed while reviewing troops. He was shot three times by Abelardo González Leiva. It was later said that González was an APRA Party member. This led to questions about whether he was ordered to attack or acted alone. Sánchez Cerro's successor as head of his political party, Revolutionary Union, was Luis A. Flores. Flores reshaped the party to be more like the fascist party in Italy.

Final Years

Óscar R. Benavides became president after Sánchez Cerro's assassination. He upheld the Salomón–Lozano Treaty with Colombia, ending the war. He also signed the General Amnesty Law on August 9, 1933, which helped the Apristas. But after a revolutionary attempt in El Agustino, the persecution of Apristas started again. The Apristas responded with terrorist acts across the country. This included the killing of Antonio Miró Quesada, owner of El Comercio, and his wife on May 15, 1935.

Under Benavides' government, new government departments were created, and tourism was encouraged. The Government Palace was renovated in 1937. The Legislative Palace and Palace of Justice were finished. Social projects were also put in place, like building dining halls and sewers.

During this time, the Spanish Civil War began in 1936. As a result, groups supporting the Republicans and the Nationalists were formed by Spanish residents in Peru and their Peruvian supporters. The Republican side was more popular among left-leaning groups, including the Apristas. The Nationalist side was more popular among the wealthy and Spanish people living in Peru. A "Spanish–Peruvian Clothing Fund" was set up in Lima. It was supposed to give clothes to children from both sides, but it mostly helped the Nationalist side. Because Peru supported the Francoist side, it did not take in Republican exiles after the war. Instead, it continued relations with the new government in Spain. The conflict increased the divide between right- and left-leaning groups, especially in cities like Arequipa.

In the last years of Benavides' government, people grew tired of his rule. On February 19, 1939, General Antonio Rodríguez Ramírez tried a coup. He seemed to have a lot of support. Although he was killed in the Government Palace, Benavides understood the message. He called for general elections. These took place on October 22 of the same year. The government's candidate, banker Manuel Prado Ugarteche, easily beat his opponent. Prado was the son of former President Mariano Ignacio Prado. There was talk of election fraud.

Democratic Spring (1939–1948)

|

Peruvian Republic

República Peruana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939–1948 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: National Anthem of Peru

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1939–1945

|

Manuel Prado Ugarteche | ||||||||

|

• 1945–1948

|

José Bustamante | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| December 8, 1939 | |||||||||

| October 27, 1948 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

With Prado as president, the Democratic Spring began. Despite the new civilian government, this era was marked by two major military conflicts: the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War and World War II.

Prado Administration

Manuel Prado became president on December 8, 1939. He was not well-known before this. People thought he wouldn't last long, but he showed great flexibility. This earned him support. His government largely continued the work started by General Benavides. He kept strong ties with the wealthy elite. It was a relatively democratic period. He kept the Aprista Party outlawed but received support from the Communist Party.

During his time as president, small fights happened with Ecuador starting on July 5, 1941. This began the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War. The situation got worse. The Peruvian Air Corps bombed Ecuadorian outposts along the border. Peru launched an offensive on July 23. Peruvian troops marched into Ecuadorian provinces like El Oro and Loja. A ceasefire was declared on the afternoon of July 31. Before that, Peruvian paratroopers attacked and occupied the port of Puerto Bolívar, near Machala.

An agreement called the Talara Accord was signed on October 2. It created a demilitarized zone in Ecuador under Ecuadorian control. The province of El Oro was occupied by Peru until the Rio Protocol was signed in January 1942. Peruvian troops left the next month. The treaty signed in Rio set up a border commission. It was supposed to mark the border between Ecuador and Peru. Most of the border was marked, but a small part remained disputed. As a result of the border being defined on the coast, cooperation between both countries grew in the following years.

Peru stayed neutral during World War II. It kept relations with countries on both sides, but favored the Allied side. On February 12, 1945, Peru was the fourth South American nation to join the Allied forces against the Axis. As part of the Japanese-American internment program, Peru gathered about 2,000 of its Japanese immigrants. They were sent to the United States and placed in concentration camps. Even though Peru joined the war late, some volunteers had already gone to Europe. For example, Jorge Sanjinez Lenz joined the Belgian Piron Brigade and fought in the Battle of Normandy.

Bustamante Administration

After the Allied victory in World War II by September 2, 1945, Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (founder of the APRA) and José Carlos Mariátegui (leader of the Peruvian Communist Party) were major forces in Peruvian politics. They had different ideas but managed to create the first political parties that addressed the country's social and economic problems. Mariátegui died young.

President Bustamante y Rivero wanted to create a more democratic government. He aimed to limit the power of the military and the wealthy elite. He was elected with APRA's help. However, conflict soon arose between the President and Haya de la Torre. Without APRA's support, Bustamante y Rivero's presidency became very limited. The President dismissed his APRA cabinet and replaced it with mostly military members. In 1948, Minister Manuel A. Odría and other right-wing members of the Cabinet urged Bustamante y Rivero to ban APRA. When the President refused, Odría resigned.

The Ochenio (1948–1956)

In a military coup on October 27, General Manuel A. Odría became the new president. Odría's presidency was known as the Ochenio (meaning "eight years"). He cracked down on APRA members and supporters. This pleased the wealthy elite and others on the right. But he also followed a populist path, which made him very popular with the poor and lower classes. A strong economy allowed him to spend money on popular social programs. However, civil rights were severely limited, and corruption was widespread during his rule.

People feared his dictatorship would last forever. So, it was a surprise when Odría allowed new elections. During this time, Fernando Belaúnde Terry began his political career. He led the National Front of Democratic Youth. When the Election Board refused to accept his candidacy, he led a huge protest. A famous image of Belaúnde walking with the flag was featured in Caretas magazine. Belaúnde's attempt to become president in 1956 failed. The right-wing candidate favored by the dictatorship, Manuel Prado Ugarteche, won.

Moderate Civil Reform (1956–1968)

Belaúnde ran for president again in the 1962 elections. This time, he ran with his own party, Acción Popular (Popular Action). The results were very close. He came in second, behind Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (APRA), by less than 14,000 votes. Since no candidate got the required one-third of the vote, Congress was supposed to choose the President. The military and APRA had a long history of not getting along. So, Haya de la Torre made a deal with former dictator Odria, who came in third. This would have made Odria president in a coalition government.

However, widespread claims of fraud led the Peruvian military to remove Prado from power. They installed a military junta led by Ricardo Perez Godoy. Godoy led a short temporary government. He held new elections in 1963. Belaúnde won these elections by a more comfortable, but still small, five percent margin. Belaúnde took office on July 28 of the same year. His presidency continued until it was interrupted in 1968.

Throughout Latin America in the 1960s, communist movements inspired by the Cuban Revolution tried to gain power through guerrilla warfare. The Revolutionary Left Movement, or MIR, started an insurrection. It was crushed by 1965. But Peru's internal problems would only get worse until the 1990s.

Radical Military Reform (1968–1980)

After a problem with a missing page from a document signed by the Peruvian government and the International Petroleum Company, General Juan Velasco Alvarado overthrew elected President Fernando Belaúnde Terry in a successful coup d'état in 1968. This was part of the military government's nationalist plan. Velasco started a big land reform program. He also took control of the fish meal industry, some oil companies, and several banks and mining companies. The Velasco government faced its worst moment during the Limazo. This was a period of unrest and riots in Lima after a strike by members of the Civil Guard and the Republican Guard.

In 1971, the country celebrated its 150th anniversary of independence. The Revolutionary Government created the National Commission for the Sesquicentennial of the Independence of Peru to manage the celebrations.

General Francisco Morales Bermúdez overthrew Velasco in 1975. He said Velasco was mismanaging the economy and was in poor health. Morales Bermúdez moved the revolution to a more traditional "second phase." He eased the radical changes of the first phase. He also began to fix the country's economy. A new constitution was written in 1979, led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre. Morales Bermúdez oversaw the return to civilian government under this new constitution. He called a general election in 1980.

Terrorism and the Fujimorato (1980–2000)

|

Republic of Peru

República del Perú

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish Quechua (1993) Aymara (1993) |

||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1980–1985

|

Fernando Belaúnde | ||||||||

|

• 1985–1990

|

Alan García | ||||||||

|

• 1990–2000

|

Alberto Fujimori | ||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||

| Historical era | Lost Decade (1980–1990) Post–Cold War (from 1991) |

||||||||

|

• 1980 Elections

|

18 May 1980 | ||||||||

|

• 1985 Elections

|

14 April 1985 | ||||||||

|

• 1990 Elections

|

8 April 1990 | ||||||||

|

• Fujishock

|

8 August 1990 | ||||||||

|

• Self-coup

|

5 April 1992 | ||||||||

|

• Tarata bombing

|

15 July 1992 | ||||||||

|

• Operación Victoria

|

12 September 1992 | ||||||||

|

• 1995 Elections

|

9 April 1995 | ||||||||

|

• Chavín de Huántar

|

22 April 1997 | ||||||||

|

• 2000 Elections

|

9 April 2000 | ||||||||

| 22 November 2000 | |||||||||

| Currency | Sol | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

In the May 1980 elections, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry was re-elected with strong support. One of his first acts was to return several newspapers to their owners. This brought back freedom of speech to Peruvian politics. He also tried to reverse some of the big changes made by Velasco's military government. He also changed the military government's independent stance with the United States.

Belaúnde's second term was also marked by his full support for Argentine forces during the Falklands War with the United Kingdom in 1982. Belaúnde stated that "Peru was ready to support Argentina with all the resources it needed." This included fighter planes and possibly personnel from the Peruvian Air Force, as well as ships and medical teams. Belaúnde's government suggested a peace agreement between the two countries. However, both sides rejected it, as they both claimed full ownership of the territory. In response to Chile's support for the UK, Belaúnde called for unity among Latin American nations.

The economic problems from the previous military government continued. They got worse due to an "El Niño" weather event in 1982–83. This caused widespread flooding in some areas and severe droughts in others. It also destroyed fish populations, which were a major resource. After a promising start, Belaúnde's popularity dropped. This was due to rising prices, economic hardship, and terrorism.

In 1985, the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) won the presidential election. This brought Alan García into office. The transfer of power from Belaúnde to García on July 28, 1985, was Peru's first peaceful change of power between two democratically elected leaders in 40 years.

With a majority in parliament for the first time, Alan García started his administration with hopes for a better future. However, poor economic management led to hyperinflation from 1988 to 1990. García's time in office was marked by periods of extremely high inflation. It reached 7,649% in 1990. The total inflation from July 1985 to July 1990 was 2,200,200%. This greatly destabilized Peru's economy.

Because of this chronic inflation, the Peruvian currency, the sol, was replaced by the Inti in mid-1985. The Inti itself was replaced by the nuevo sol ("new sun") in July 1991. At that time, one new sol was worth one billion old soles. During his time in office, the average annual income for Peruvians dropped to $720 (below 1960 levels). Peru's GDP fell by 20%. By the end of his term, national reserves were negative $900 million.

The economic problems made social tensions worse in Peru. This partly led to the rise of the violent rebel group Shining Path. The García government tried to use military force to stop the growing terrorism, but it failed. Human rights violations were committed during this time and are still being investigated.

In June 1979, protests for free education were harshly stopped by the army. Official figures said 18 people were killed, but other estimates suggest dozens died. This event led to more extreme political protests in the countryside. It eventually caused the Shining Path to start its armed and terrorist actions.

Fujimori's Presidency and the Fujishock (1990–2000)

People were worried about the economy. They were also concerned about the growing terrorist threat from Sendero Luminoso and MRTA. There were also accusations of government corruption. So, in 1990, voters chose a relatively unknown mathematician-turned-politician, Alberto Fujimori, as president. The first round of the election was won by famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa. He was a conservative candidate who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010. But Fujimori defeated him in the second round. Fujimori took strong actions that made inflation drop from 7,650% in 1990 to 139% in 1991. The currency lost 200% of its value. Prices rose sharply, especially gasoline, which multiplied by 30. Hundreds of state-owned companies were sold off, and 300,000 jobs were lost. Most people did not benefit from the years of strong growth. This only made the gap between rich and poor wider. The poverty rate stayed around 50%.

Fujimori dissolved Congress in the self-coup of April 5, 1992. He did this to have complete control of the government. He then got rid of the constitution. He called new congressional elections. He also made big economic changes. These included selling many state-owned companies, creating a good environment for investment, and managing the economy well.

Fujimori's government faced several rebel groups. The most notable was Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path). They carried out a terrorist campaign in the countryside throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Fujimori cracked down on the rebels. He was largely successful in stopping them by the late 1990s. However, the fight was marked by terrible acts committed by both Peruvian security forces and the rebels. These included the Barrios Altos massacre and La Cantuta massacre by government groups. The Shining Path carried out bombings like Tarata and Frecuencia Latina. These events later became symbols of human rights violations during the last years of violence. With the capture of Abimael Guzmán (known as President Gonzalo to the Shining Path) in September 1992, the Shining Path was severely weakened.

In December 1996, a group of rebels from the MRTA took over the Japanese embassy in Lima. They held 72 people hostage. Military commandos stormed the embassy in April 1997. All 15 hostage-takers, one hostage, and two commandos died. It later came out that Fujimori's security chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, might have ordered the killing of at least eight rebels after they surrendered.

Fujimori's decision to seek a third term was questioned by the constitution. His victory in June 2000 was also seen as unfair. This led to political and economic chaos. The Four Quarters March from July 26–28 resulted in several deaths and injuries. It also destroyed the building of the Banco de la Nación. A bribery scandal broke out just weeks after he took office in July. This forced Fujimori to call new elections, in which he would not run. The scandal involved Vladimiro Montesinos. A video showed him bribing a politician to switch sides. Montesinos later became known as the center of many illegal activities. These included stealing money, corruption, and human rights violations during the war against Sendero Luminoso.

Business Republic (2000–2016)

In November 2000, Fujimori resigned and went to Japan. He stayed there to avoid being charged with human rights violations and corruption by Peruvian authorities. His main intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, fled Peru shortly after. Authorities in Venezuela arrested him in Caracas in June 2001. They handed him over to Peruvian authorities. He is now in prison, charged with corruption and human rights violations during Fujimori's time in office.

A temporary government led by Valentín Paniagua took charge. Its job was to hold new presidential and congressional elections. The elections were held in April 2001. Observers said they were free and fair. Alejandro Toledo (who led the opposition against Fujimori) defeated former President Alan García.

The new government took office on July 28, 2001. The Toledo Administration managed to bring back some democracy to Peru. This was after the strict rule and corruption that affected both the Fujimori and García governments. Innocent people wrongly tried by military courts during the war against terrorism (1980–2000) were allowed to have new trials in civilian courts.

On August 28, 2003, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) presented its official report to the President. This commission had been tasked with studying the causes of the violence from 1980–2000.

President Toledo had to change his cabinet several times. This was mostly due to personal scandals. Toledo's ruling group had few seats in Congress. He had to work with other parties to pass laws. Toledo's popularity dropped in his last years. This was partly due to family scandals. It was also due to workers being unhappy with their share of Peru's economic success. After strikes by teachers and farmers in May 2003, Toledo declared a state of emergency. This suspended some civil liberties and gave the military power to enforce order in 12 regions. The state of emergency was later reduced to only the areas where the Shining Path was active.

On July 28, 2006, former president Alan García was reelected as President of Peru. He won the 2006 elections after a runoff against Ollanta Humala. In May 2008, President García signed The UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations. Peru has approved this treaty.

On June 5, 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected president. He won in a runoff against Keiko Fujimori, Alberto Fujimori's daughter and former First Lady of Peru, in the 2011 elections. This made him Peru's first leftist president since Juan Velasco Alvarado. In December 2011, a state of emergency was declared. This followed public opposition to some large mining projects and environmental concerns.

Political Crisis (2016–Present)

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was elected president in the general election in July 2016. His parents were Jewish European refugees who fled Nazism. Kuczynski wanted to include and recognize Peru's native populations. State-run TV began daily news broadcasts in Quechua and Aymara. Kuczynski was widely criticized for pardoning former President Alberto Fujimori. This went against his campaign promises against his rival, Keiko Fujimori.

In March 2018, after failing to remove the president, Kuczynski again faced the threat of impeachment. This was based on accusations of vote buying and bribery with the Odebrecht corporation. On March 23, 2018, Kuczynski was forced to resign from the presidency. His successor was his first vice president, engineer Martín Vizcarra. Vizcarra publicly stated he had no plans to seek re-election amid the political crisis and instability. However, Congress impeached President Martin Vizcarra in November 2020. His successor, interim president Manuel Merino, resigned after only five days in office. Merino was succeeded by interim president Francisco Sagasti, the third head of state in less than a week.

On July 28, 2021, coinciding with Peru's 200th anniversary of independence, left-wing Pedro Castillo was sworn in as the new President of Peru. He won by a small margin against Keiko Fujimori in the 2021 election.

Due to economic problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru, between 10% and 20% of Peruvians fell below the poverty line in 2020. This reversed a decade of poverty reduction. The poverty rate reached 30.1% that year. Following global economic effects from Western sanctions against Russia due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, inflation in Peru rose sharply. As a result, mass protests began on March 28, 2022. The government responded by sending in the Armed Forces. President Castillo declared a state of emergency and enforced a total curfew in Lima for April 5. In November 2022, thousands of government opponents marched in the capital. They called for President Pedro Castillo's removal.

After multiple attempts to remove Castillo failed, Castillo tried a self-coup on December 7, 2022. He was then impeached and removed from office. Castillo's vice president Dina Boluarte was sworn in as the new president later that day. She became the country's first female president. After Castillo's removal, his supporters started nationwide protests. They demanded his release and Boluarte's resignation. On December 14, 2022, Peru's new government declared a 30-day national state of emergency to stop violent demonstrations.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Perú para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Perú para niños

- History of the Americas

- Politics of Peru