Belgian government in exile facts for kids

The Belgian Government in London was the official government of Belgium during World War II. It was based in London, United Kingdom, from October 1940 to September 1944. This government was made up of ministers from three main political parties: the Catholic, Liberal, and Labour Parties.

When Nazi Germany invaded Belgium in May 1940, the Belgian government, led by Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot, had to leave the country. They first went to Bordeaux, France, and then moved to London. There, they became the only recognized Belgian government by the Allied powers.

Even though they were not in Belgium, this government still managed the Belgian Congo. They also worked with other Allied countries to plan for Belgium's future after the war. Important agreements they made included creating the Benelux Customs Union and helping Belgium join the United Nations. The government also guided the Belgian army-in-exile and tried to stay in touch with the underground resistance groups back home.

Contents

Why the Government Left Belgium

Belgium's Neutrality and Invasion

Before World War II, Belgium tried to stay neutral and not pick sides in international conflicts. They wanted to have good relationships with Britain, France, and Germany. However, on May 10, 1940, Germany invaded Belgium without warning.

After 18 days of fighting, the Belgian army surrendered on May 28. Germany then took control of the country. About 600,000 to 650,000 Belgian men, which was almost 20% of the male population, had been called to fight.

King Leopold III's Decision

Unlike the leaders of the Netherlands and Luxembourg, whose kings and queens went into exile with their governments, King Leopold III chose to surrender to the Germans. He did this against the advice of his government. The King remained a prisoner of the Germans, under house arrest, for the rest of the war.

The Belgian government tried to talk with the German authorities from France. But Germany issued a rule that stopped Belgian government members from returning home. So, the talks ended.

Setting Up in London

Finding Safety in France

The Belgian government first went to Limoges, France. They planned to follow the French government to its colonies to keep fighting. While in Limoges, they spoke out against King Leopold's surrender. However, when the French government changed and became more friendly with Germany, the Belgian government's plan changed too.

Even though the new French government (called the Vichy regime) was not welcoming, the Pierlot government stayed in France for a while. But the Vichy government soon demanded that the Belgian government break up.

Moving to London

While the main government was still in France, the Belgian Minister of Health, Marcel-Henri Jaspar, arrived in London on June 21. He thought the Pierlot government might surrender to Germany and wanted to stop it. Jaspar spoke on BBC radio, saying he was forming a new government to keep fighting. The Pierlot government in France did not approve of this.

However, Jaspar's actions pushed the Pierlot government to act. Albert de Vleeschauwer, the Minister of the Colonies, arrived in London. He was the only Belgian minister who had legal power outside Belgium. He, along with Camille Gutt, who arrived soon after, formed a temporary "Government of Two" with Britain's approval.

They waited for Paul-Henri Spaak and Prime Minister Pierlot to join them. Pierlot and Spaak had been held in Francoist Spain on their way from France. They finally reached London on October 22, 1940. This formed the "Government of Four," which was seen as the official Belgian government because it included the last elected Prime Minister. The British government, though hesitant at first, accepted them.

Most of the Belgian government set up offices in Eaton Square in London. This area was close to other governments-in-exile, like those from Luxembourg and the Netherlands. By December 1940, the British officially recognized this "government of four" as the legal government of Belgium.

Who Was in the Government

Initially, there were only four ministers. But soon, many more politicians and civil servants joined. They worked in different government departments, mainly for the Colonies, Finance, Foreign Affairs, and Defence. By May 1941, about 750 people worked for the Belgian government in London.

The "Government of Four"

| Job | Name | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prime Minister – Public Education and Defence | Hubert Pierlot | Catholic | |

|

Foreign Affairs, Information and Propaganda | Paul-Henri Spaak | POB-BWP | |

|

Financial and Economic Affairs | Camille Gutt | None (expert) | |

|

Colonies and Justice | Albert de Vleeschauwer | Catholic | |

Other Ministers

Some ministers did not have a specific department but still played important roles. They were called "Ministers without Portfolio."

What the Government Did

The government in exile had to act like a normal national government. It also had to represent Belgium to the Allied powers. Paul-Henri Spaak once said that "all that remains of legal and free Belgium... is in London."

Other countries, like Britain and the United States, sent their ambassadors to work with the Belgian government in exile. Even the Soviet Union, which had stopped talking to Belgium earlier, re-established its diplomatic ties in 1943.

Helping Belgian Refugees

One of the first big tasks for the government was helping Belgian refugees in the United Kingdom. By 1940, at least 15,000 Belgian civilians had arrived in Britain, often without their belongings. The government set up a Central Service of Refugees to help them with money and jobs.

At first, some British people were not friendly towards Belgian refugees. This was because they believed Belgium had betrayed the Allies when King Leopold III surrendered. The government also helped set up schools and cultural places for Belgians in Britain. For example, the Belgian Institute was created in London in 1942.

Building the Free Belgian Forces

After the Belgian surrender, Prime Minister Pierlot called for a new army to be formed outside Belgium. He wanted them to continue the fight alongside the Allies.

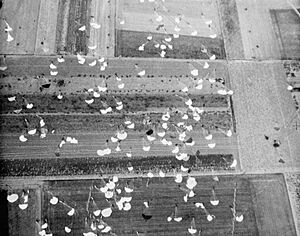

Some Belgian soldiers were saved from Dunkirk and brought to England. Along with Belgians already living in England, they formed the "Belgian Military Camp for Regrouping" in Wales. By July 1940, there were 462 Belgians in the camp, growing to nearly 700 by August. These soldiers became the 1st Fusilier Battalion. Belgian airmen also joined the Royal Air Force, and later, two all-Belgian squadrons were created. A Belgian section was also formed within the Royal Navy.

For a while, there was some disagreement between the government and the army. The army felt the government wasn't letting them fight enough. But by 1943, the army's loyalty shifted more towards the government.

Signing Treaties and Agreements

In September 1941, the Belgian government signed the Atlantic Charter with other governments in exile. This document outlined the common goals the Allies wanted to achieve after the war. A year later, in January 1942, Belgium signed the Declaration by United Nations with 26 other countries. This was an important step towards forming the United Nations Organisation in 1945.

From 1944, the Allies started planning for how Europe would be after the war. In July 1944, Camille Gutt represented Belgium at the Bretton Woods Conference in the United States. This meeting set up the Bretton Woods System for controlling currencies. Gutt played a key role in these talks. The agreements made there tied the Belgian Franc's value to the American Dollar after the war. The conference also created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and Gutt became its first director.

In September 1944, the Belgian, Dutch, and Luxembourg governments in exile began planning a Customs Union. This agreement was signed on September 5, 1944, just days before the Belgian government returned to Brussels. This union was a big step from an earlier agreement between Belgium and Luxembourg. It later became the basis for the Benelux Economic Union after 1958.

How the Government Paid for Itself

Unlike many other governments in exile, the Belgian government could pay for itself. This was mainly because it controlled most of Belgium's national gold reserves. These gold reserves had been secretly moved to Britain in May 1940.

The Belgian government also controlled the Belgian Congo. This colony provided large amounts of raw materials like rubber, gold, and uranium, which were very important for the Allied war effort.

The Belgian government also published its own official newspaper, the Moniteur Belge, from London.

Relationship with King Leopold III

King Leopold III's decision to surrender to the Germans without talking to his government made the cabinet very angry. For the first few years of the war, some people, including members of the Free Belgian military, saw the King as an alternative leader. This made the official government in London seem less important.

Later in the war, the government changed its approach. Belgian propaganda began to show the King as a "martyr" and a prisoner-of-war. They presented him as suffering alongside the people in occupied Belgium. In a radio speech in May 1941, Pierlot asked Belgians to "rally around the prisoner-King."

According to Belgium's constitution, the government could overrule the King if he was declared unable to rule. On May 28, 1940, the Pierlot government in France declared the King unable to reign because he was under the power of the invaders. This gave the government strong legal power and made it the only official government.

When the government returned to Belgium, the issue of the King was still a big debate. On September 20, 1944, after Belgium was freed, Leopold's brother, Charles, was declared the temporary ruler (prince regent).

Working with the Resistance

The Jaspar-Huysmans government, even before the French surrender, called for organized resistance in occupied Belgium from London.

The official government in London gained control over the French and Dutch radio broadcasts to occupied Belgium. These were broadcast by the BBC's Radio Belgique. This radio station was vital for keeping the resistance and the public informed. Victor de Laveleye, a former minister, worked as a newsreader and is known for inventing the "V for Victory" campaign.

In the early war years, it was hard for the government to contact the resistance groups in Belgium. A permanent radio connection with the largest group, the Armée Secrète, was only set up in 1944.

Because the government in exile seemed far away from events in Belgium, many resistance groups were suspicious of it. The government, on the other hand, worried that resistance groups might become uncontrollable after liberation. Despite this, the resistance often needed money, equipment, and supplies that only the government in exile and the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) could provide. The government sent millions of Belgian francs to the Armée Secrète and other groups during the war.

In May 1944, the government tried to improve its relationship with the resistance. They created a "Coordination Committee" with representatives from the main groups. However, Belgium was liberated soon after, making the committee less necessary.

Returning to Belgium

Allied troops entered Belgium on September 1, 1944. On September 6, the capital, Brussels, was freed. The Belgian government in exile returned to Brussels on September 8, 1944. A plan called "Operation Gutt," created by Camille Gutt, was put into action. It helped prevent high inflation in liberated Belgium by controlling the money supply, and it was very successful.

On September 26, Pierlot formed a new government in Brussels. This new government included many of the ministers from London, and for the first time, also included the Communists. In December 1944, a new government was formed, with Pierlot still as Prime Minister. In 1945, after being Prime Minister since 1939, Pierlot was replaced by Achille Van Acker.

The government in exile was one of the last governments where the traditional political parties that had led Belgium for a long time were still dominant. After 1945, these parties changed their names.

See also

- Belgian Congo in World War II

- Belgium in World War II

- Free French Forces

- German occupation of Belgium during World War II

- Politics of Belgium

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |