Ecuadorian–Peruvian territorial dispute facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Peruvian–Ecuadorian Wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the South American territorial disputes | |||||||

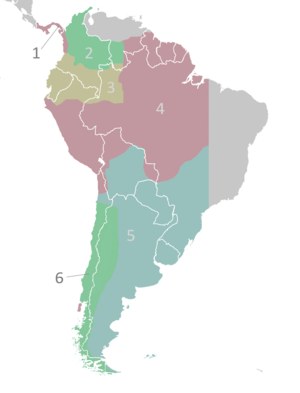

Map of the disputed territories from 1916 onwards |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The Ecuadorian–Peruvian territorial dispute was a long-standing disagreement over land between Ecuador and Peru. For a while, Colombia was also involved. This argument started because each country had a different idea of how Spain had drawn its colonial borders in the Americas.

After they became independent, these new countries agreed to use the uti possidetis juris principle. This meant their new borders would be the same as Spain's borders in 1810. However, different claims and disagreements often led to armed conflicts.

The dispute was supposed to end after the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War in 1941, with the signing of the Rio de Janeiro Protocol in 1942. But this treaty was questioned, and the two countries fought again in the Paquisha War (1981) and the Cenepa War (1995).

Finally, on October 26, 1998, Ecuador and Peru signed a peace agreement. This agreement helped end the border dispute for good. The official marking of the border began in May 1999, and both countries' governments approved the agreement.

Contents

- Spanish Rule and Early Borders

- Wars of Independence

- Gran Colombia–Peru Conflict

- Treaties and Events (1832–1856)

- Ecuadorian–Peruvian War (1857–1860)

- Boundary Negotiations and Treaties (1860–1941)

- Ecuadorian–Peruvian War (1941)

- Paquisha War (1981)

- Cenepa War (1995)

- Arbitration and Final Resolution (1995–1998)

- Aftermath

- See also

- Images for kids

Spanish Rule and Early Borders

Spanish Conquest and New Governments

When Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492, Spain began to take control of many lands in the Americas. By 1528, Spanish explorers reached the Inca Empire. In 1532, Francisco Pizarro started the Spanish conquest of Peru, taking advantage of a civil war within the Inca Empire. Over the next few decades, Spain took full control of the Andean region.

To rule these new lands, King Charles I of Spain created two large governments called Viceroyalties in 1542. These were the Viceroyalty of New Spain (in modern-day Mexico) and the Viceroyalty of Peru (in South America). The Viceroyalty of Peru was officially organized in 1572.

Dividing the Land in Peru

Because the Viceroyalty of Peru was so huge, it was divided into smaller areas called audiencias (royal courts). These courts acted like major provinces, handling both legal and executive matters. They helped govern the land far from the main cities of Lima.

From 1542 to 1717, the Viceroyalty of Peru controlled most of South America. Its territory was divided into several audiencias, including:

- Royal Audience of Santa Fe de Bogotá (1548)

- Royal Audience of San Francisco of Quito (1563)

- Royal Audience of the City of Kings Lima (1543)

The borders of these audiencias were set by royal decrees from the Spanish King. These laws were collected over time in books like the Recopilación de las Leyes de los Reynos de Indias (1680). This book helped define the borders of Lima and Quito.

Creating New Granada

In 1717, King Philip V of Spain created a new government called the Viceroyalty of New Granada. This new viceroyalty was formed by taking the northwestern part of Peru. New Granada included lands that are now Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. It also included parts of northern Peru and western Guyana.

The Royal Audience of Quito, created in 1563, was part of New Granada. Its territory stretched from Pasto in the north to Piura in the south. The eastern border, towards the Amazon, was not very clear at first. But as missionaries explored the Amazon, the borders became better defined. In 1740, a new royal decree clearly set the border between New Granada and Peru.

This 1740 decree stated that the border would start at the Tumbes River on the Pacific coast. It would then follow the Andes mountains through Paita and Piura to the Marañón River. This decree was the first time the Tumbes River was mentioned as a border between the two viceroyalties.

The Royal Decree of 1802

In 1802, the Spanish King Charles IV of Spain issued a new decree called the Real Cédula of 1802. This decree moved the control of the Maynas and Governorate of Quijos regions from New Granada to the Viceroyalty of Peru. These areas were along the Napo River and other rivers flowing into the Marañón River.

This decree caused a lot of confusion. Some copies of the document were different, making people wonder if they were all real. Also, it wasn't clear if this change was only for military and church matters, or if it also changed the actual land borders. This lack of clarity became a big problem for Ecuador and Peru when they became independent.

Events from 1803 to 1818

- 1803: The military control of Guayaquil, an important port city, was given to Lima.

- 1810: All administrative and economic control of Guayaquil was given to Peru.

- 1812: A Spanish decree tried to cancel the 1802 decree, but it didn't fully resolve the issue.

- 1816: The King of Spain officially canceled the 1802 decree, returning Maynas to Quito.

- 1818: The Viceroy of Peru acknowledged the 1816 order, confirming that Maynas was returned to Quito.

Wars of Independence

The Republic of Gran Colombia was formed in 1819, led by Simón Bolívar. Its independence battles freed lands that are now Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. General Antonio José de Sucre helped free Ecuador in 1822.

Gran Colombia included what is now Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Panama. Bolívar dreamed of uniting all of South America, but this never happened.

Even before the wars ended, Bolívar said that the new countries' borders should follow the old Spanish administrative borders from 1809. This was the uti possidetis juris principle. So, the Viceroyalty of Peru became the Republic of Peru, and the Viceroyalty of New Granada became Gran Colombia.

However, Peru started claiming land based on the 1802 decree (for the Amazon region) and the 1803 decree (for Guayaquil). Gran Colombia argued that these decrees only changed church or military control, not political borders. They based their claims on the 1740 decree.

- July 6, 1822: Monteagudo-Mosquera Treaty

- This treaty was an alliance between Gran Colombia and Peru against Spain. It also aimed for Peru to recognize Guayaquil as part of Gran Colombia. The exact border was left for a future agreement.

Gran Colombia–Peru Conflict

Simón Bolívar wanted to keep Gran Colombia united. But Peruvian President José de la Mar had his own ambitions. De la Mar wanted to restore the old Inca Empire by adding Ecuador and Bolivia to Peru. This led to a quick rivalry between Bolívar and De la Mar.

De la Mar started a campaign against Bolívar, gaining support in Peru and Bolivia. In June 1828, De la Mar invaded southern Gran Colombia, occupying Loja and trying to take Guayas.

Bolívar declared war on Peru. General Sucre led the Colombian Army. In 1829, De la Mar's forces were defeated at the Battle of Tarqui. A coup in Peru led to a peace treaty. The Convenio de Girón recognized the borders as they were before independence. In July, the Piura Armistice recognized Guayaquil as part of Gran Colombia. The war officially ended in September 1829.

- February 28, 1829: La Mar-Sucre Convention

- This agreement was signed after the Battle of Tarqui. It ended Peru's attempt to take parts of Gran Colombia by force.

- September 22, 1829: Larrea-Gual Treaty

- This treaty confirmed the uti possidetis principle. It also allowed for small changes to create a more natural border. Both sides agreed to form a group to set a permanent border.

Gran Colombia broke apart in 1830 due to political problems. Ecuador became a separate country on May 13, 1830. Its first constitution, adopted in September 1830, stated that Ecuador included the provinces of Azuay, Guayas, and Quito.

Confusion about Gran Colombia

Today, we use "Gran Colombia" to talk about the federation of Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela before 1830. But back then, it was just called "Colombia."

In Peru, some believed that when Gran Colombia dissolved, all treaties it signed became invalid. This meant new countries like Ecuador had no claim to those treaties. However, Ecuador and Colombia believed that the new countries inherited the treaties that applied to their land.

The Pedemonte-Mosquera Protocol

Ecuador and Colombia say that the Pedemonte-Mosquera Protocol was signed in Lima on August 11, 1830. This protocol was supposed to settle the eastern border from the Andes to Brazil, making the Marañón River and Amazon River the new boundary. It also set the western border at the Macará and Tumbes rivers. However, a small area in the Andes called Jaén de Bracamoros remained disputed.

Ecuador has always used this protocol to support its land claims. But Peru has questioned if the protocol ever truly existed:

- The original document has never been found.

- The people who supposedly signed it might have been in different places at the time.

- Neither country's government officially approved it.

- Ecuador had already left Gran Colombia a month before the supposed signing date.

Even though it seems unlikely Ecuador would invent such a treaty, the missing original document makes it hard to prove. Ecuador has produced a copy from 1870, but Peru still disputes it.

Treaties and Events (1832–1856)

- February 10, 1832: Ecuador's Separation Recognized

- The Republic of Nueva Granada (Colombia) officially recognized Ecuador as a new nation.

- July 12, 1832: Pando-Noboa Treaty

- Peru recognized Ecuador as a new republic. They signed a friendship treaty, agreeing to respect their current borders until a new agreement was made.

- 1841–1842: Border Talks Fail

- Ecuador demanded the return of Tumbes, Jaén, and Maynas. Peru refused, saying these areas were already Peruvian. Talks failed because Ecuador insisted on getting Jaén and Maynas back.

- October 23, 1851: Peru-Brazil Treaty

- Peru set its eastern border with Brazil. But Ecuador and Colombia protested, saying part of this border was in disputed Amazon territories.

- March 10, 1853: Peru Creates Loreto Government

- Peru created a special government for its Amazon region, called Loreto. This was to strengthen its claim by exploring and settling these areas with Peruvian citizens.

Ecuadorian–Peruvian War (1857–1860)

This war was fought over disputed land near the Amazon. In 1857, Ecuador tried to give some land in the Canelos region to Britain to pay off a debt. Peru protested, saying this land belonged to Peru based on the 1802 decree.

Despite Peru's complaints, Ecuador continued talks with the British. This led to Peru occupying and blocking Guayaquil in 1859. On February 25, 1860, the Treaty of Mapasingue was signed. Ecuador canceled the land deal with Britain, and Peru withdrew its forces. However, the exact border was still unclear.

Boundary Negotiations and Treaties (1860–1941)

- 1864: Peruvian Navy in Iquitos

- Peruvian Navy steamships arrived in Iquitos, establishing a naval base. This helped Peru control the Amazonian rivers.

- August 1, 1887: Espinoza-Bonifaz Convention

- Ecuador and Peru agreed to let the King of Spain decide their border dispute. But Ecuador pulled out before the decision was made, saying the King was not fair. The King then did not issue a decision.

- May 2, 1890: Herrera-García Treaty

- After the failed arbitration, Ecuador and Peru tried direct talks. This treaty gave Ecuador access to the Amazon and Napo rivers, and control over parts of Tumbes, Maynas, and Canelos. Ecuador's government approved it, but Peru's government added changes that reduced Ecuador's control. Ecuador then rejected the modified treaty.

- 1903–1904 Incidents

- There were small military clashes in the Napo River area. Peruvian forces pushed back Ecuadorian troops.

- May 6, 1904: Tobar–Rio Branco Treaty

- Ecuador signed a treaty with Brazil, giving up its old Spanish colonial claims to land in present-day Brazil.

- July 15, 1916: Muñoz-Suarez Treaty

- This treaty ended a long border dispute between Colombia and Ecuador. It set a new border line from the Pacific Ocean to the Amazon River. Ecuador gave up some of its old claims to land north of the Caqueta River.

- June 21, 1924: Ponce-Castro Oyangurin Protocol

- Ecuador and Peru agreed to negotiate their border issues in Washington, D.C. Ecuador claimed all of Tumbes, Jaén, and Maynas, but was willing to compromise. Peru considered these areas already theirs and only wanted to define their borders. Because they couldn't agree on what land was disputed, the talks failed in 1937.

- July 6, 1936: Ulloa-Viteri Accord

- This agreement set a temporary border based on who controlled what land in the Amazon at the time. This line was similar to the one in the 1942 Rio Protocol. Ecuador saw it as proof of how much land Peru had taken, and did not consider it a final border.

Ecuadorian–Peruvian War (1941)

In 1941, the two countries went to war again. Both sides have different stories about who started it. Peru says Ecuador had been entering its territory since 1937. Ecuador says Peru's invasion was unprovoked and aimed at forcing Ecuador to sign an unfair treaty.

Peru had a much larger and better-equipped army of 13,000 men. Ecuador had only about 1,800 troops in the province of El Oro. Peru also had tanks, artillery, and air support. Ecuador's army had no warplanes.

On July 5, 1941, fighting broke out along the border. Peruvian forces quickly overwhelmed the Ecuadorian troops. Peru even used paratroopers, which was the first time in the Western Hemisphere.

With Peru occupying El Oro and threatening Guayaquil, and pressure from the United States and other Latin American countries, Peru and Ecuador signed the Rio de Janeiro Protocol.

Rio de Janeiro Protocol

In May 1941, before the war, the United States, Brazil, and Argentina offered to help settle the dispute. Their efforts didn't stop the war, but they helped arrange a ceasefire on July 31.

On January 29, 1942, Ecuador and Peru signed the "Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries" in Rio de Janeiro. The United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile co-signed, becoming "Guarantors of the Protocol." Both countries' governments approved it in February 1942.

Under the Protocol, Ecuador gave up its claim to direct access to the Marañón and Amazon rivers. Peru agreed to remove its troops from Ecuadorian land. A large area of disputed land in the Amazon basin was given to Peru, as Peru had been controlling it since the late 1800s. The border was based on the 1936 agreement, which recognized who controlled what land.

Ecuador's Objections to the Protocol

During the border marking process, problems arose. One area, the Cordillera del Cóndor, was difficult to define. In 1949, Ecuador's president Galo Plaza stopped the border marking because a river, the Cenepa, was found to be much longer than thought. This conflicted with the treaty's description. About 78 kilometers of the border were left unmarked.

On September 29, 1960, Ecuadorian president José María Velasco Ibarra declared the Rio Protocol invalid. Ecuador argued that:

- It was signed under military force.

- It was signed while Peruvian troops occupied Ecuadorian towns.

- International law does not allow taking land by force.

- Peru did not allow Ecuador free navigation on Amazonian rivers as promised.

Peru argued that:

- Ecuador could not cancel the treaty by itself.

- The problem was about marking the border, not invalidating the whole treaty.

- Peru did not invade with the goal of forcing the treaty.

- Ecuador's government approved the treaty long after Peruvian troops left.

Ecuador argued its case for 30 years but found little international support. Peru believed the dispute was over after 1941. Maps in Ecuador from the 1960s often showed the disputed areas as still belonging to Ecuador.

Paquisha War (1981)

The Paquisha War was a short military clash in January and February 1981. It was over control of three military posts. Peru felt the issue was settled by the 1941 war, but Ecuador disagreed with the Rio de Janeiro Protocol. Later, in 1998, the countries guaranteeing the Rio Protocol confirmed that the border in the disputed area was indeed the Cordillera del Cóndor line, as Peru had claimed.

After this incident, both sides increased their military presence. This led to more tension and another conflict in 1995, the Cenepa War.

Cenepa War (1995)

The Cenepa War was a short conflict from January to February 1995. It was fought over a disputed area on the border. Ecuador had disagreed with the 1941 treaty regarding the Cenepa and Paquisha areas.

The war ended without a clear winner. Both sides claimed victory. With help from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and the United States, diplomatic talks began. These talks led to a final peace agreement, the Brasilia Presidential Act, signed on October 26, 1998. The border was officially marked in May 1999, finally ending one of the oldest land disputes in the Americas.

Arbitration and Final Resolution (1995–1998)

After the Cenepa War, the four guarantor countries helped arrange a ceasefire. The Itamaraty Peace Declaration was signed in February 1995. This created the Military Observer Mission Ecuador-Peru (MOMEP) to monitor the ceasefire.

MOMEP included observers and support from the United States, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. Both Peru and Ecuador paid for the mission. MOMEP was very successful in preventing more fighting.

The guarantors helped both countries discuss their claims. They agreed to have experts define the border. Political changes in both countries caused delays, but the guarantors used this time to find a solution.

The experts recognized Ecuador's position on a small part of the border. But they agreed with Peru on the larger issue of the watershed between the Zamora and Santiago rivers. This meant Tiwintza would be in Peruvian territory.

The solution was to give Ecuador a one-square-kilometer area in Tiwinza, on the Peruvian side, as private property. Ecuador could use this site for special events, but it would not be sovereign land. Everyone born in Tiwinza would be considered Peruvian. Neither country was completely happy, but both accepted the solution.

The agreement also called for creating two national parks next to each other in the Cordillera del Condor region.

On October 26, 1998, Ecuador and Peru signed the peace agreement. The border was officially marked starting May 13, 1999. Both countries' governments approved it. U.S. President Bill Clinton said this signing marked the end of the last and longest armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere.

Aftermath

This dispute is important for understanding how international conflicts start and end. Ecuador and Peru share a language, culture, and similar economic situations. They are also both democracies, which challenges the idea that democracies never fight each other.

Education and Public Views

A study in 2000 found that how the dispute was taught in schools was very one-sided in both countries.

- In Ecuador, the dispute was a main topic in "History of Borders" classes.

- In Peru, it was less important and part of "Peruvian History." Only the 1942 Rio Protocol was usually taught.

Both countries' teaching materials often left out information about the other side's views. This likely fueled the conflict in the past. Citizens in both countries felt they had lost land over time.

High military spending by Peru was seen by Ecuador as a sign of aggression. Peru also saw Ecuador as aggressive.

By the end of the 20th century, things improved a lot. The Cenepa War of 1995 allowed for an honorable end to the conflict without a clear winner. Many Ecuadorians felt this restored their country's honor.

Today, the entire border between Ecuador and Peru is clearly marked, and both countries' maps agree. They are now working together on economic and social projects.

Economic Impact

Both countries were concerned about how the dispute affected foreign investment. Peace was seen as key to South America's economic recovery. Without stability, long-term growth and foreign investment are difficult.

Trade between the two countries has greatly improved. Before the peace treaty, annual trade was about $100 million. By 1998, it had increased five times.

There was also a broad agreement for integration, including a fund for peace and development, and plans for economic and social growth.

Political Implications

The Ecuadorian–Peruvian dispute challenged several ideas about international relations:

- It showed that democracies can go to war with each other, even if they are not perfect.

- It reminded everyone that Latin America still has other land disputes that could cause problems.

- It highlighted the need for civilian leaders to have stronger control over military actions, especially if conflicts start from small incidents.

- It questioned the idea that land treaties in Latin America are never the result of force.

See also

- Bolivian–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Colombian–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Ecuador–Peru relations

- Dispute resolution

- Territorial dispute

- Paquisha Incident

- General Richelieu Levoyer

Images for kids

-

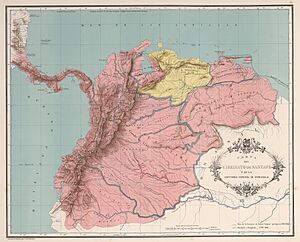

Map of a Peruvian school in Callao showing the territories claimed by Peru in 1937.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |