Inca road system facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Inca road system |

|

|---|---|

| Qhapaq Ñan | |

Extent of the Inca road system

|

|

Section of the Inca road

|

|

| Route information | |

| Length | 40,000 km (20,000 mi) |

| Time period | Pre-Columbian South America |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Qhapaq Ñan, Andean Road System |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Inscription | 2014 (38th Session) |

| Area | 3,642.8067 ha (9,001.571 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 728,448.256 ha (1,800,034.84 acres) |

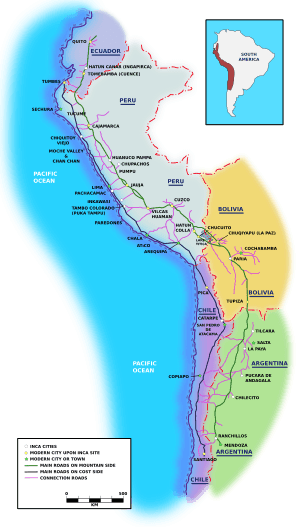

The Inca road system (also called Inka road system or Qhapaq Ñan, meaning "royal road" in Quechua: Quechua) was an amazing network of paths built in ancient South America. It was the most advanced transportation system of its time. This huge network stretched for about 40,000 kilometres (25,000 mi) in total. Building these roads took a lot of time and effort.

The Inca roads were carefully planned and built. They included paved sections, stairways for climbing hills, and many bridges. There were also important structures like retaining walls and drainage systems. The main system had two long roads running north to south. One followed the coast, and the other, more important one, went high up into the mountains. Many smaller roads branched off these main routes.

You can compare this road system to the famous Roman roads, even though the Incas built theirs about a thousand years later. These roads helped the Tawantinsuyu (Inca Empire) move information, goods, soldiers, and people. They did all this without using wheels! The empire covered almost 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) and had about 12 million people.

Along the roads, there were special buildings. At short distances, there were relay stations for chasquis, who were fast running messengers. Every day's walk, there were tambos (rest stops). These provided support for travelers and their llama pack animals. You could also find administrative centers with large warehouses called qullqas. These warehouses stored goods for distribution. Near the edges of the Inca Empire, there were also pukaras (fortresses).

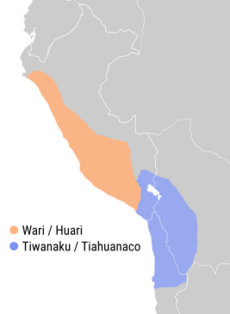

Some parts of the road network were built by older cultures. These included the Wari culture in Peru and the Tiwanaku culture in Bolivia. Today, organizations like UNESCO and IUCN work to protect these roads. They work with the governments and communities in the six countries the Great Inca Road passes through. These countries are Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

Even today, some parts of the roads are popular with tourists. The Inca Trail to Machu Picchu is a famous example for hikers. A study in 2021 showed that living near the Inca Road still has benefits. Communities within 20 kilometers of the road often have better wages, nutrition, and school levels. This shows the lasting impact of this ancient system.

Contents

Exploring the Great Inca Road System

The Inca road system was incredibly vast. It connected what is now Peru, Ecuador, and parts of Colombia to the north. To the south, it reached into modern-day Argentina and Chile. The roads linked these distant areas with the Inca capital city, Cusco. The system covered about 5,000 kilometres (3,100 mi) of the Andes mountains. The Andes stretch for over 7,000 kilometres (4,300 mi).

One historian, Hyslop, noted that the main mountain route was over 5,658 kilometres (3,516 mi) long. This route passed through important cities like Quito, Tumebamba, Huánuco, and Cusco. The exact total length of the road network is still debated. Estimates range from 23,000 kilometres (14,000 mi) to 60,000 kilometres (37,000 mi).

There were two main north-south routes. The eastern route went high up in the `puna grassland`, which is a large, flat area above 4,000 metres (13,000 ft). The western route started near Tumbes on the coast. It followed the coastal plains, avoiding the driest deserts. This western road is similar to where the modern Pan-American Highway runs in South America.

Recent studies suggest another branch existed on the eastern side of the Andes. This branch connected the administrative center of Huánuco Pampa to the Amazonian areas. It was about 470 kilometres (290 mi) long. More than twenty roads crossed the western mountains. Other roads went over the eastern mountains and lowlands. These connected the two main routes to populated areas, farms, mines, and sacred sites. Some of these roads reached amazing altitudes, over 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) above sea level.

Connecting the Empire: The Four Main Routes

During the Inca Empire, all major roads officially started from Cusco. Cusco was considered the "navel of the Earth" by the Incas. These roads went in four main directions, leading to the four suyus (regions) of the Tawantinsuyu.

The four regions were:

- Chinchaysuyu: To the North. This was the most important route. It was wide (3 to 16 m) and connected major administrative centers like Vilcashuamán and Cajamarca in Peru, and Ingapirca in Ecuador.

- Collasuyu: To the South. This route left Cusco and split to go around Lake Titicaca. It then continued through the Bolivian Altiplano. One branch went to Argentina, and another to Chile, reaching the Maipo river.

- Contisuyu: To the West. These roads connected Cusco to the coastal areas of Peru. They helped move different natural resources between the mountains and the coast.

- Antisuyu: To the East. These roads went into the "Ceja de Jungla" (edge of the jungle) towards the Amazon rainforest. These paths are less known because the jungle makes it hard for ancient structures to survive.

Why the Roads Were Built

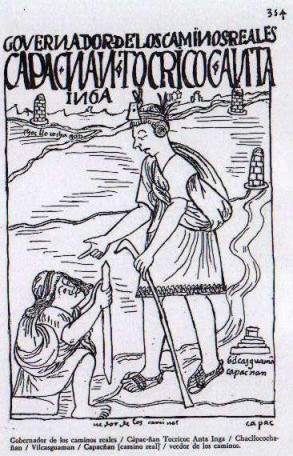

The Incas used their road system for many important reasons. These included travel for people, military movements, and religious journeys. The roads allowed for quick movement of people across the empire. Armies and workers used the roads and rested at tambos. Information and small valuable goods also traveled fast through the chasquis. The Incas often built roads as straight as possible to save time.

Historians believe the roads were key to the Inca Empire's growth. Important settlements were often built along these main roads. The Incas preferred to build roads in the high plains (`Altiplano` or `puna`) areas. This helped them avoid crowded valleys and create direct routes. These high plains also had cool, dry climates, which were perfect for storing goods. For example, the administrative center of Huánuco Pampa had 497 large warehouses (`collcas`). These could store enough food for thousands of people. `Collcas` were used for long-term storage, especially for grains like maize, which was vital for feeding the army.

Historian Hyslop suggested that only authorities could use the Inca roads. This included soldiers, porters, llama caravans, and nobles on official duties. Other people needed special permission to use them. However, there was likely some private travel and trade too. Small local structures along the roads suggest that people might have bartered goods.

After the Spanish conquest of Peru, the Inca roads were mostly abandoned. The Spanish used horses and ox carts, which were not suitable for these roads. Many roads fell into disuse. Today, only about 25 percent of the original network is still visible. Wars, changes in the economy, and modern construction destroyed much of the rest.

Fast Travel and Communication

People traveled on foot in pre-Columbian America, as the wheel was not used for transportation. The Incas had two main ways of moving things on their roads:

- Chasquis: These were fast runners who relayed information. They carried messages, often in the form of knotted strings called quipus. They also transported lightweight valuables across the empire.

- Llama Caravans: Llamas were used as pack animals. They are light animals and cannot carry heavy loads. However, they are very agile. To move many goods, the Incas used large herds of llamas with a few herdsmen. Llamas have soft hooves, which gave them good grip on mountain roads and did not damage the surface. A llama of the Q'ara race (short-haired) could carry about 30 kilograms (66 lb) for 20 kilometres (12 mi) a day. They could carry up to 45 kilograms (99 lb) for shorter trips.

Sharing Resources and Trade

Roads and bridges were vital for keeping the Inca state united. They also helped distribute goods throughout the empire. All resources belonged to the ruling class. There was no buying and selling between individuals. Instead, the central government managed all goods. This system of distributing resources was called the vertical archipelago. Different parts of the empire had different resources. The roads ensured that goods were moved to where they were needed. This system made the Inca Empire strong by satisfying all its regions. However, some historians believe that caravanners and villagers might have traded goods locally.

Military and Expansion

The roads provided easy, fast, and reliable routes for the empire's military and administrative needs. They helped move troops, supplies, and officials. When the Incas conquered a new area, they would extend their road system into it. This made the Qhapaq Ñan a lasting symbol of Inca power in new territories. The roads helped armies move quickly for new conquests or to stop rebellions. They also helped share surplus goods with newly added populations.

Forts, or pukaras, were mainly built in border areas. They showed where the empire was expanding. Many pukaras are found in the north, where the Incas were adding new lands. In the south, forts near Mendoza, Argentina, and the Maipo river in Chile, marked the empire's southernmost reach.

Sacred Journeys and Beliefs

High-altitude shrines were very important to Inca beliefs. They were linked to the worship of Nature, especially mountains. Mountains were seen as apus, or powerful deities, in Andean beliefs. The Incas held special ceremonies and offerings, sometimes involving valuable goods and llamas, at these sacred mountain tops. Not all mountains had shrines, but those that did were reached by connecting the road system to high-altitude paths. These were ritual roads leading to peaks, seen as places where the earthly and sacred worlds met. Some roads reached incredible heights, like the one on Mount Chañi, which went to the summit at 5,949 metres (19,518 ft).

Besides mountain shrines, there were many other holy sites called wak’a. These were part of the Zeq’e system and were found along and near the roads, especially around Cusco. Wak’a could be natural features or modified structures where Incas would visit to worship. Important places of worship, like the sanctuary of Pachacamac, were directly connected by the main Inca roads.

A Look Back: History of the Inca Roads

Building on Older Paths

Much of the Inca road system was built on older routes. The Incas took over and improved many traditional paths. Some of these had been built centuries earlier by cultures like the Wari empire in Peru and the Tiwanaku culture around Lake Titicaca. These older cultures had developed advanced civilizations between the 6th and 12th centuries CE. The Incas built many new sections and greatly improved existing ones. For example, they built a road through Chile's Atacama desert.

The Inca Empire's Golden Age

The Inca Empire began to grow around 1438. Inca Pachakutiq started to expand the empire from the Cusco region. The Incas' strategy involved building or improving roads to connect new territories to Cusco. This allowed troops and officials to move easily. The Incas often tried to make diplomatic deals before conquering new regions. Topa Inca Yupanqui continued this expansion, reaching Quito around 1463 and extending south into Chile.

Spanish conquerors later used these roads. For example, Diego de Almagro's expedition to Chile followed the Inca road from Cusco south.

Changes After the Spanish Arrival

During the early colonial period, the Qhapaq Ñan was largely abandoned. The number of native people decreased greatly due to illness and war. This destroyed the social structure that maintained the roads. The Spanish focused on mining and trade with the coast, which changed how the land was used. New routes were opened to connect mines and farms to coastal ports. Many Inca roads, especially those leading to forts or agricultural centers, were no longer used. However, some ritual roads to sacred sites continued to be used.

A chronicler named Cieza de Leon noted in 1553 that the road was "already broken down and undone." The Spanish rulers did not maintain the system. They also moved local populations into new settlements, which further led to the abandonment of old roads. The new animals introduced by the Spanish, like horses and mules, were not suited for the Inca roads. This also contributed to their disuse. New farming methods from Spain also changed the landscape, sometimes damaging ancient farming terraces.

However, some parts of the network, like the tambos, continued to be used. They became stores and meeting places, adapting to new ways of life.

Modern Times and Preservation

After gaining independence from Spain, the new American republics in the 19th century did not make many changes to the road system. The focus remained on connecting mountain production to the coast for export. Modern roads and railways were built to support this. They prioritized coastal connections and routes into valleys to channel goods to seaports. Some Inca roads in the southern Altiplano were still used to access centers for producing alpaca and vicuña wool. These wools were in high demand internationally.

In the 20th century, the Pan-American Highway was built along the coast. It followed parts of the old coastal Inca road. This highway was then connected to east-west routes into the valleys. The main north-south Inca road in the mountains was mostly reduced to local walking paths.

In 2014, the Inca road system was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This helps protect this amazing ancient network for future generations.

How the Roads Were Built

The Incas were brilliant engineers. They built their road system by improving many existing smaller networks. They created a formal system with careful maintenance. This huge network, stretching across the continent, started from Cusco and went in the four main directions of the Tawantinsuyu. This allowed the Inca rulers to know what was happening everywhere in their empire.

The Incas developed clever ways to build roads in the tough Andes mountains. On steep slopes, they built stone steps. In coastal deserts, they built low walls to stop sand from covering the road.

Smart Engineering and Construction

The labor for building and maintaining the roads came from the mita system. This was a type of tax paid through work. Conquered people provided labor to the state. This included keeping roads, bridges, tambos, and warehouses in good condition.

Officials, often nobles from Cusco, managed this work. There were managers for royal roads, bridges, and chasquis. There were also builders of landmarks.

Special Features of the Roads

There was no single way to build the roads because the landscapes were so different.

Roadway and Pavement

In the mountains and high forests, the Incas used carefully placed paving stones. They made sure the flat side faced up to create a smooth surface. However, not all roads were paved. In the high plains (`puna`) and coastal deserts, roads were often made of packed earth, sand, or simply by covering grassland with soil. Some roads even had paving made of plant fibers.

The width of the roads varied. They were usually between 1 and 4 metres (3.3 and 13.1 ft) wide. But some, like the road to Huánuco Pampa, could be much wider, up to 25 metres (82 ft). The main road from Cusco to Quito was always wider than 4 metres (13 ft), even in valuable farming areas. Some parts reached 16 metres (52 ft) wide. Near cities, there might even be two or three roads built side-by-side.

Side Walls and Stone Rows

Stones and walls marked the edges of the road. On the coast and in the mountains, walls made of stone or mud bricks (`adobes`) were built. These walls separated the road from farmland. This kept travelers and llama caravans from damaging crops. In flat and desert areas, these walls likely stopped sand from drifting onto the road. In very deserted areas, stone rows or wooden poles were used as markers.

Retaining Walls

Retaining walls were built on hillsides using stones, `adobes`, or mud. These walls held back soil that might slide down the slope. They also created flat platforms for the road. You often see them on roads that go from the mountains to the coast.

Drainage

Drainage ditches and culverts were common in the mountains and jungle. This was because of heavy rainfall. In other areas, rain water was drained using a system of long channels and shorter drains that crossed the road. When roads crossed wet areas, they were often built on raised causeways with supporting walls.

Road Marks

At certain distances, stone piles called mojones (milestones) marked the road's direction. These were usually placed on both sides of the road. They were often on high spots so travelers could see them from far away.

Apachetas were mounds of stones built by travelers. People would add a stone as an offering to ensure a safe journey. These were found at passes or important points. During the colonial period, this practice was discouraged, and crosses were often placed instead. However, the tradition of building apachetas continued.

Paintings and Mock-ups

Some rock shelters or cliffs next to the roads have rock paintings. These might have helped mark the way. The paintings often show stylized llamas or alpacas, in typical Inca designs. Figures carved directly into stone are also found. Some rocks along the road were shaped to look like mountains or glaciers. This showed the sacred importance of the landscape.

Causeways

In wet areas, the Incas built raised earth platforms called causeways. In rocky areas, they sometimes dug the path directly into the rock. Or they built artificial terraces with retaining walls. Some important causeways near Lake Titicaca were built to handle changes in the lake's water level. They even had stone bridges to let water flow underneath.

Stairways

To deal with steep and difficult terrain, Inca engineers built stairways or ramps. These were sometimes carved directly into the rock. This allowed the road to climb very steep slopes.

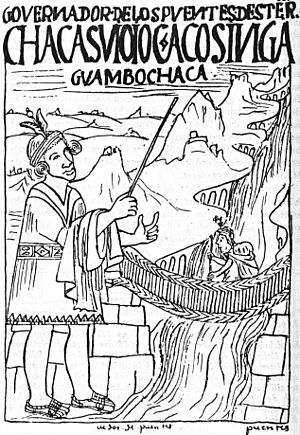

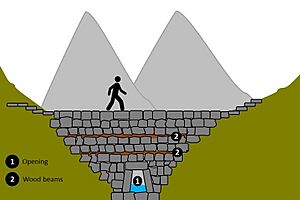

Bridges

The Incas built many types of bridges, sometimes in pairs. Some were made of logs tied together with ropes, covered with earth and plant fibers. These rested on stone supports. Others were made of stone slabs on top of piled stones. Getting logs for wooden bridges could be difficult, as workers sometimes had to bring them from far away. Wooden bridges were replaced about every eight years.

Building bridges required many workers. First, they built strong stone supports. The stone work was often very precise, with stones fitting together perfectly without mortar. The Incas used simple tools like hammerstones to shape rocks.

Stone bridges could cross shorter distances and shallower rivers. A special stone bridge was found in Bolivia. It had a small opening for a stream and a large stone embankment for the road to pass over.

To cross rivers with flat banks, the Incas used floating reed boats. These were tied together in a row and covered with reeds and earth.

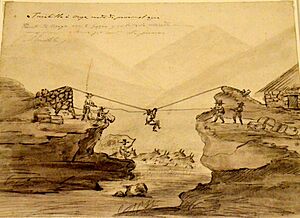

Inca rope bridges were used to cross narrow valleys. A famous one over the Apurímac River, west of Cusco, was 45 metres (148 ft) long. Rope bridges needed to be replaced about every two years. Local communities would work together to build a new bridge. These bridges were made from strong ropes of plant fibers, like ichu grass. These ropes formed the bridge floor, handrails, and connections.

Ravines were sometimes crossed using large hanging baskets called oroyas. These could span over 50 metres (160 ft).

Tunnel

To reach the famous Apurímac rope bridge, the road had to go through a very narrow part of the gorge. A tunnel was carved into the steep rock to make this possible. The tunnel had side openings to let in light. This is the only known tunnel along the Inca roads.

Rest Stops and Messenger Stations

The Inca road system had many important facilities. These included lodging posts for state officials and chasqui messengers. These were well-spaced and well-stocked. Food, clothes, and weapons were also stored for the Inca army.

The tambos were the most common and important buildings. They were structures of different sizes and designs. Their main purpose was to provide lodging for travelers and store supplies. They were usually located about a day's journey apart. However, their distances varied, possibly due to water sources or nearby farms. Tambos were likely managed by local people. Many were part of larger settlements with other buildings. These included canchas (rectangular enclosures for travelers) and kallancas (large rectangular buildings for ceremonies and lodging). Tambos were so common that many place names in the Andes still include the word "tambo."

Along the roads, there were also chasquiwasis, or relay stations for the Inca messengers. Here, chasquis waited for messages to carry to other places. Fast communication was crucial for the expanding empire. Chasquiwasis were usually small, and not much archaeological evidence remains of them.

The Famous Inca Trail to Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu was a special royal estate, not a major city. It was home to the ruling Inca and many servants. It needed a constant supply of goods and services from Cusco and other parts of the empire. This is why there are no large government storage buildings at the site. A study in 1997 showed that the farms around Machu Picchu could not have fed all its residents, even seasonally. The Inca Trail was essential for connecting this important site to the rest of the empire.

See also

In Spanish: Red vial del Tahuantinsuyo para niños

In Spanish: Red vial del Tahuantinsuyo para niños