Alexander Ross Clarke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Ross Clarke

|

|

|---|---|

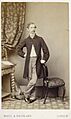

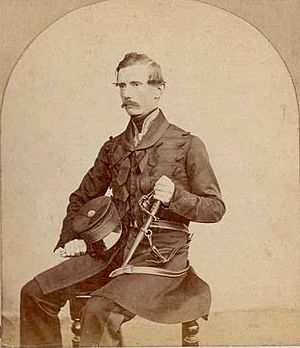

Alexander Ross Clarke in 1861

|

|

| Born | 16 December 1828 Reading, England

|

| Died | 11 February 1914 (aged 85) Reigate, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | The Principal Triangulation of Great Britain, Reference ellipsoids, Textbook on geodesy. |

| Awards | Royal Medal of the Royal Society, Companion of the Order of the Bath |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geodesy |

| Institutions | Ordnance Survey |

Alexander Ross Clarke (1828–1914) was a brilliant British scientist known as a geodesist. A geodesist is someone who studies the Earth's shape and size. He is famous for his work with the Ordnance Survey, which is the national mapping agency of Great Britain.

Clarke calculated the first detailed map of Great Britain, called the Principal Triangulation of Great Britain. He also figured out the shape of the Earth and wrote an important textbook on geodesy. He was an officer in the Royal Engineers, a special part of the British Army.

Contents

Who was Alexander Ross Clarke?

Early Life and Education (1828–1850)

Alexander Ross Clarke was born in Reading, England, on December 16, 1828. His father was from Scotland, and his mother was from Jamaica. Alexander spent some of his early childhood in Jamaica. He later told his own children fun stories about growing up there.

His family moved back to England and then to Scotland. Alexander's schooling was tough but effective. He learned Latin and mathematics, which he was very good at. His math skills helped him choose his future career.

When he was 17, Clarke applied to the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He didn't prepare much for the entrance exam, so he started at the bottom of his class. But he worked very hard and became the top student. He was known as an "exceptionally capable young man." In 1847, he became a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers.

After Woolwich, Clarke studied surveying and military engineering at the Royal School of Military Engineering in Chatham. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1849.

Working at the Ordnance Survey (1850–1881)

In 1849, Clarke decided he wanted to work for the Ordnance Survey. He joined in 1850 when the government approved money for a big mapping project. This was a great chance for him because the Survey needed skilled people.

Before he could start, Clarke was sent to Canada for military service. While there, he met and married Frances Maria. She was the daughter of his commanding officer.

In 1854, Clarke became the main person responsible for analyzing the Principal Triangulation of Great Britain. This was a huge job, but he finished the main report by 1858. For his hard work, he was promoted to 2nd Captain in 1855. In 1856, he became the head of the Trigonometrical and Levelling Departments at the Ordnance Survey.

Clarke worked on many important projects for 27 years. He wrote many detailed reports about his findings. All his experience from these years was put into his famous textbook, Geodesy.

Clarke's work made the Ordnance Survey very famous. He was recognized as one of the best geodesists in the world. He became a member of the Royal Society of London in 1862. He also received the Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath in 1870. He continued to be promoted in the army, reaching the rank of Colonel in 1877.

Clarke and his wife had a large family with nine daughters and four sons. They lived in Southampton. Even with a big family, Clarke preferred to work from home.

Retirement and Later Life (1881–1914)

In 1881, Clarke was ordered to go to Mauritius for military service. He didn't want to leave his life's work at the Ordnance Survey, so he resigned from the Army. Many scientists protested, but his resignation was accepted. His departure was a big loss for the Survey.

After retiring, Clarke's involvement with geodesy became less frequent. He attended some international conferences, but he didn't publish new work on the subject. However, his fame remained strong. He received the prestigious Royal Medal from the Royal Society of London in 1887. This award recognized his work on comparing length standards and determining the Earth's shape.

The award citation praised his "unique knowledge and power" in geodesy. It also noted that his work helped solve a problem between different ways of measuring the Earth's shape. His findings were considered the best at the time.

Clarke moved to Reigate with his wife and daughters. His wife died in 1888. He had to sell his Royal Medal for money, but he gave half to charity. Even though he stopped working on geodesy, he remained mentally active. He enjoyed microscopy, music, and religion.

Alexander Ross Clarke passed away on February 11, 1914, in Reigate. He was considered the most important geodesist in Britain for many years.

What were Clarke's main contributions to geodesy?

Mapping Great Britain (1858)

The Principal Triangulation of Great Britain was a huge project to map the country accurately. It started in 1791, and the fieldwork finished in 1853, just as Clarke joined the Ordnance Survey. Clarke was given the job of finishing the calculations and writing the final report.

He completed this massive task in just four years (1854-1858). He used a method called least squares error analysis. This method helps find the most likely correct measurements when you have many observations. He had to solve 920 equations without computers! The only "computers" were the 21 people working in his section.

The survey was incredibly accurate. When they calculated the length of a base line in Ireland from a base line in England, the error was only 5 inches over about 8 miles. This showed how precise Clarke's work was.

Figuring out the Earth's Shape (1858, 1866, 1880)

Clarke also worked on figuring out the exact shape of the Earth. The Earth isn't a perfect sphere; it's an ellipsoid, meaning it's slightly flattened at the poles and bulges at the equator.

- 1858: Clarke used the British mapping data to find the best-fitting ellipsoid for Great Britain. He then combined this data with measurements from other countries.

- 1860: Some scientists thought the Earth's equator might be slightly elliptical (oval-shaped). Clarke studied this, but he found that the measurements weren't accurate enough to prove it.

- 1866: To make international mapping more accurate, Clarke supervised detailed comparisons of different length standards (like feet, yards, and meters). This helped combine measurements from different countries. He then used this new data to calculate an even better model for the Earth's shape. This model, known as the Clarke 1866 ellipsoid, became very important. The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey adopted it in 1880, and it's still used for many US maps and legal documents today.

- 1880: In his famous textbook Geodesy, Clarke presented another updated model for the Earth's shape. This one is called the Clarke 1880 ellipsoid and is used by many African countries.

Measuring Heights (1861)

Besides mapping positions, the Ordnance Survey also measured the exact height of many important points across Britain. This was done using a method called spirit levelling. Clarke was responsible for preparing the reports for England and Scotland. He used mathematical methods to find the most accurate heights for these points.

International Mapping Connections (1863)

Clarke also played a key role in connecting the mapping surveys of different European countries. This allowed scientists to measure a very long arc (a curved line) along the 52nd parallel north. This huge measurement helped improve the calculations for the Earth's shape even more.

His Textbook Geodesy (1880)

Clarke's book Geodesy was the first major book on the subject in a long time. It was very popular and translated into many languages. It covered everything from how to measure distances and angles to how to calculate the Earth's shape.

Other Writings

Clarke also wrote several articles for scientific journals, mostly about geodesy. He also contributed two important articles to the Encyclopædia Britannica (a famous encyclopedia) in 1878. These articles were about "Geodesy" and the "Figure of the Earth." He later updated these articles with another scientist, and also wrote a new article about "Maps."

See also

- Alwyn Robbins

- History of the metre

- Seconds pendulum

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |