Louis Auguste Blanqui facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

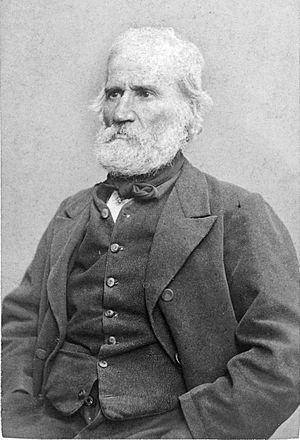

Louis Auguste Blanqui

|

|

|---|---|

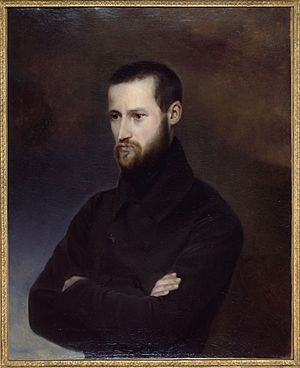

Portrait by his wife, Amelie Serre Blanqui, circa 1835.

|

|

| Born | 8 February 1805 |

| Died | 1 January 1881 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Revolutionary, philosopher |

| Known for | Blanquism |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui |

Louis Auguste Blanqui (born February 8, 1805 – died January 1, 1881) was a French socialist and political activist. He is famous for his revolutionary ideas, known as Blanquism.

Contents

About Louis Auguste Blanqui

Early Life and Political Actions (1805–1848)

Louis Auguste Blanqui was born in Puget-Théniers, France. His father, Jean Dominique Blanqui, was a local official. Louis had an older brother, Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, who became a well-known economist.

Blanqui first studied law and medicine. But he soon found his true passion in politics. He quickly became a strong supporter of new and bold ideas.

He joined a secret society called the Carbonari in 1824. This group worked for political change. Blanqui took part in many republican plots during this time. In 1827, he was seriously hurt in a street fight.

In 1829, he worked for a newspaper called Globe. He then joined the July Revolution of 1830. This revolution changed the government in France. After that, he joined the "Friends of the People" society. Here, he met other important thinkers like Philippe Buonarroti and Armand Barbès.

Blanqui believed in a republic, where people would elect their leaders. Because of his strong beliefs, he was often sent to prison. This happened many times during the rule of King Louis Philippe (1830–1848). In 1832, during a trial, Blanqui famously said that the workers' actions would inspire people worldwide.

In May 1839, an uprising happened in Paris. Blanqui's ideas inspired this event. He was a key member of the Société des Saisons (Society of the Seasons). He was sentenced to death in 1840, but this was changed to life imprisonment.

Release and More Imprisonment (1848–1879)

Blanqui was set free during the revolution of 1848. But he was not happy with the changes. He started a group called the Société républicaine centrale. This group demanded more government changes. His strong actions caused problems with other, more moderate republicans. In 1849, he was sent to prison again for ten years.

While in prison, he wrote a short message to a group of social democrats in London. Karl Marx later read and shared this message.

In 1865, Blanqui was in prison again. But he managed to escape! He continued to speak out against the government from other countries. In 1869, a general amnesty (a pardon for political prisoners) allowed him to return to France.

Blanqui believed in using force to bring about change. In 1870, he led two attempts to protest. One was at the funeral of a journalist named Victor Noir. The other was an attempt to take guns from a military barracks.

When the French Empire fell in September 1870, Blanqui started a club and a newspaper called La patrie en danger (The Homeland in Danger).

On October 31, Blanqui and his group briefly took control of the government. For this, he was sentenced to death again in March 1871, but he was not there for the trial. On March 17, Adolphe Thiers, a government leader, had Blanqui arrested.

A few days later, the Paris Commune uprising began. The people of Paris elected Blanqui as their president. The Communards offered to release all their prisoners if the government released Blanqui. But the government refused. So, Blanqui could not take part in the Commune. Karl Marx later thought that the Commune missed Blanqui's leadership.

In 1872, Blanqui was sentenced to be sent away to a distant prison colony. But because he was very sick, this was changed to regular imprisonment. On April 20, 1879, he was elected as a representative for Bordeaux. Even though the election was later declared invalid, Blanqui was freed. He immediately went back to his political work.

Blanqui's Ideas

As a socialist, Blanqui wanted a fair way to share wealth among people. However, his ideas, called Blanquism, were different from other socialist movements.

Unlike Karl Marx, Blanqui did not believe that the working class would lead the revolution. He thought that a small, strong group should carry out the revolution. This group would set up a temporary dictatorship (a government with total power). This temporary rule would help create a new society. After that, power would be given to the people.

Blanqui was more focused on the revolution itself. He was less focused on what the future socialist society would look like. He was different from utopian socialists, who imagined perfect societies. For Blanquists, overthrowing the old system and having a revolution were the main goals. He was one of the socialists of his time who did not follow Marx's ideas.

His Death

After giving a speech in Paris, Blanqui had a stroke. He died on January 1, 1881. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His tomb was designed by the artist Jules Dalou.

Blanqui's Legacy

Blanqui was a very strong radical. He believed in using force to make changes. This led him to clash with every French government during his life. Because of this, he spent half of his life in prison.

Besides his many newspaper articles, he wrote a book called L'Eternité par les astres (1872). In this book, he shared his ideas about eternal return. This is the idea that events in the universe repeat themselves forever. After he died, his writings on money and society were collected in a book called Critique sociale (1885).

The Italian fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, started by Benito Mussolini, had a quote by Blanqui on its front page: Chi ha del ferro ha del pane. This means "He who has iron has bread." It suggests that power comes from strength.

Blanqui's political work and his book L'Eternité par les astres were discussed by the philosopher Walter Benjamin. They are also mentioned in the novel The Secret Knowledge by Andrew Crumey.

See also

In Spanish: Louis Auguste Blanqui para niños

In Spanish: Louis Auguste Blanqui para niños

- French demonstration of 15 May 1848

- La patrie en danger

- No gods, no masters

- Eternal return

Works

French

- L'Armée esclave et opprimée

- Critique sociale: Capital et travail

- Critique sociale: Fragments et notes

- Instructions pour une prise d'armes.

- Maintenant il faut des armes

- Ni dieu ni maitre

- Qui fait la soupe doit la manger

- Réponse

- Un dernier mot

English translations

- The Eternity According to the Stars, translated by Mathew H. Anderson, 2009.

- Eternity by the Stars. Translated by Frank Chouraqui, 2013.